Sixty-six million years ago, the reign of the dinosaurs, a dynasty spanning an incredible 180 million years, came to a cataclysmic end. This abrupt finale wasn’t due to old age or evolutionary obsolescence, but rather a devastating cosmic collision. A massive asteroid struck the Earth, triggering a chain of events that led to the extinction of not only the non-avian dinosaurs but also approximately 75% of plant and animal species on the planet. The question of exactly Where Did The Asteroid Hit That Killed The Dinosaurs has been a subject of intense scientific investigation, and the answer lies buried beneath the waters off the coast of Mexico.

In 1980, a groundbreaking theory emerged from Nobel Prize-winning physicist Luis Walter Alvarez and his geologist son Walter. They proposed that a distinctive layer of clay, rich in the element iridium, found globally at the geological boundary marking the end of the Cretaceous period, was the result of a large asteroid impact. Iridium is rare in the Earth’s crust but is found in higher concentrations in meteorites and asteroids. The Alvarez hypothesis suggested that this impact event caused immediate destruction and far-reaching secondary effects, ultimately leading to the swift demise of the dinosaurs.

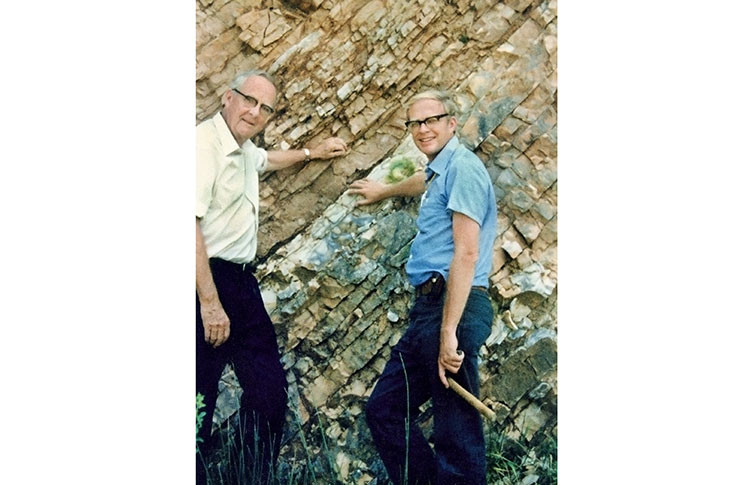

Luis Walter and son Walter Alvarez

Luis Walter and son Walter Alvarez

Initially met with skepticism, the Alvarez hypothesis has become the most widely accepted explanation for the mass extinction event that marks the end of the Mesozoic Era. Subsequent research has unearthed compelling evidence to support this theory, most notably the discovery of the impact crater itself.

The definitive evidence supporting the asteroid impact theory is the Chicxulub crater. As dinosaur researcher Prof Paul Barrett from the Natural History Museum explains, ‘An asteroid impact is supported by really good evidence because we’ve identified the crater. It’s now largely buried on the seafloor off the coast of Mexico. It is exactly the same age as the extinction of the non-bird dinosaurs, which can be tracked in the rock record all around the world.’

The Chicxulub crater, answering the question of where did the asteroid hit that killed the dinosaurs, is centered on the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico. This massive geological scar is a testament to the scale of the impact event. While the asteroid itself is estimated to have been between 10 and 15 kilometers in diameter, the immense energy released upon impact carved out a crater a staggering 150 kilometers wide. This makes it the second-largest confirmed impact crater on Earth, a dramatic reminder of the colossal forces at play 66 million years ago.

Pieces of iridium

Pieces of iridium

The impact at Chicxulub unleashed unimaginable devastation. The collision vaporized the asteroid and a significant portion of the Earth’s crust at the impact site. Gigantic volumes of debris, including dust, soot, and vaporized rock, were ejected high into the atmosphere. Massive tidal waves, or megatsunamis, radiated outwards from the impact zone, inundating coastlines across the Americas. Furthermore, evidence suggests that the impact triggered widespread wildfires, adding to the immediate chaos and destruction.

The scientific dating of the iridium layer and the Chicxulub crater consistently points to 66.0 million years ago, coinciding precisely with the revised date of the dinosaur extinction. This precise dating strengthens the link between the asteroid impact at Chicxulub and the demise of the dinosaurs and many other life forms on Earth.

But how did an impact in what is now Mexico lead to a global mass extinction, wiping out approximately three-quarters of all species on Earth? The key lies in the long-lasting global environmental consequences triggered by the Chicxulub impact.

As Prof Paul Barrett elaborates, ‘The asteroid hit at high velocity and effectively vaporised. It made a huge crater, so in the immediate area there was total devastation. A huge blast wave and heatwave went out and it threw vast amounts of material up into the atmosphere… It sent soot travelling all around the world. It didn’t completely block out the Sun, but it reduced the amount of light that reached the Earth’s surface. So it had an impact on plant growth.’

An illustration of an asteroid impacting Earth

An illustration of an asteroid impacting Earth

The sunlight-blocking effect of the atmospheric debris had profound consequences for plant life. Reduced sunlight hampered photosynthesis, leading to a decline in plant growth and productivity. This, in turn, initiated a cascading collapse of the food chain. Herbivorous dinosaurs, dependent on plants for sustenance, suffered from food shortages. Subsequently, carnivorous dinosaurs, who preyed on herbivores, also faced starvation.

The ecological disruption extended beyond dinosaurs. Ammonites, a diverse group of shelled cephalopods that thrived in the oceans for millions of years, vanished entirely. Microscopic plankton, the foundation of marine food webs, were decimated. Large marine reptiles, such as mosasaurs and plesiosaurs, also succumbed to extinction. The asteroid impact at where it hit in the Yucatán Peninsula triggered a global environmental catastrophe with far-reaching consequences across ecosystems.

While the asteroid impact at Chicxulub is widely recognized as the primary driver of the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event, it’s important to acknowledge that Earth’s environment was already undergoing significant changes prior to the impact. Massive volcanic eruptions in the Deccan Traps region of present-day India had been ongoing for millions of years. These eruptions released vast quantities of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, contributing to global climate change.

Prof Barrett notes, ‘For two million years there was a huge amount of volcanic activity going on, spewing gases into the atmosphere and having a major impact on global climate… There were also longer-term changes. The continents were drifting around and splitting apart from each other, creating bigger oceans, which changed ocean and atmosphere patterns around the world. This also had a strong effect on climate and vegetation.’

A selection of ammonites from the Museum

A selection of ammonites from the Museum

These pre-existing environmental stresses likely made ecosystems more vulnerable to the sudden shock of the asteroid impact. The Deccan Traps volcanism, coupled with long-term continental drift and associated climate shifts, set the stage for the mass extinction, with the asteroid impact acting as the final, decisive blow.

Despite the widespread devastation, life did persist. Plants, due to the resilience of their seeds and pollen, were less severely affected than animals. Flowering plants, which had already begun to diversify during the Cretaceous, flourished in the aftermath, eventually dominating terrestrial ecosystems. Among animals, smaller species were more likely to survive than larger ones. Notably, all land animals exceeding 25 kilograms in weight perished.

‘What we’re left with are basically the seeds of what we have today. Many of the major animal groups that are alive today were in place before the asteroid impact and they all suffered some level of extinction – but the lines that led to modern animals got through,’ explains Prof Barrett. Crucially, while non-avian dinosaurs went extinct, their avian relatives, birds, survived and diversified, becoming the dominant lineage of dinosaurs we see today.

The fossilised skull of an extinct flightless bird

The fossilised skull of an extinct flightless bird

The world after the asteroid impact was initially dominated by smaller animals. It took millions of years for larger animals to re-evolve. Mammals, which were relatively small and inconspicuous during the age of dinosaurs, began to diversify and fill the ecological niches left vacant by the extinct giants. It wasn’t until the Oligocene Epoch, approximately 15 million years after the dinosaur extinction, that mammals comparable in size to rhinos began to appear.

Interestingly, recent research suggests that the location of the asteroid impact played a critical role in the severity of the extinction event. Had the asteroid struck just minutes earlier or later, it would have landed in deeper ocean waters. An impact in a deep ocean environment would have vaporized less rock, resulting in less debris being ejected into the atmosphere, potentially mitigating the global sunlight-blocking effect and lessening the severity of the mass extinction.

A Triceratops skeleton

A Triceratops skeleton

Speculating on a counterfactual history, Prof Barrett suggests, ‘I suspect some of them would still be around. We don’t know a lot about the last 10 million years of their reign and what we do know is based on only one area in the world, western North America. There is a really good record of those classic last non-bird dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops… From that part of the world it looks like dinosaurs are thriving in terms of numbers, but the number of different types of dinosaurs is reduced. We don’t know if that pattern held elsewhere – it’s still a big mystery.’

In conclusion, the asteroid that ended the reign of the dinosaurs struck off the coast of Mexico, on the Yucatán Peninsula, creating the Chicxulub crater. This impact, while not the sole cause, was the pivotal event that triggered a global mass extinction, reshaping life on Earth and paving the way for the rise of the mammals and the world we inhabit today. The precise location where the asteroid hit was a crucial factor in the unfolding catastrophe, highlighting the delicate balance of Earth’s ecosystems and the profound consequences of cosmic events.