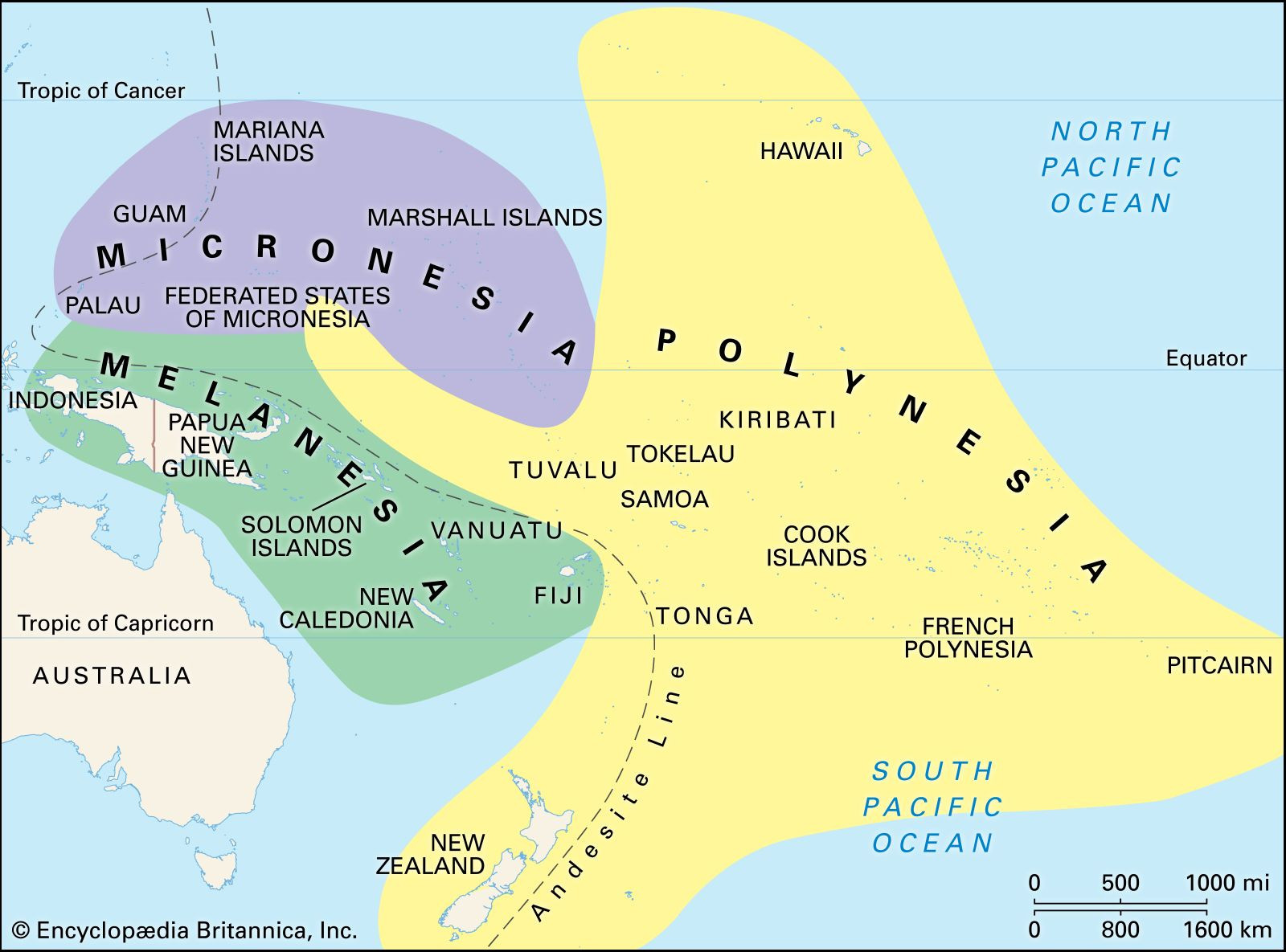

Polynesia, a term derived from the Greek words “poly” meaning “many” and “nēsoi” meaning “islands,” aptly describes a vast and culturally rich region scattered across the east-central Pacific Ocean. But Where Is Polynesia exactly? This expansive ethnogeographic group of Pacific islands forms a triangle with its northern apex at the Hawaiian Islands, its western base angle at New Zealand (Aotearoa), and its eastern point at Easter Island (Rapa Nui).

This immense Polynesian Triangle encompasses a diverse array of island nations and territories, each contributing to the vibrant tapestry of Polynesian culture. To pinpoint where is Polynesia on a map, visualize this triangle stretching across thousands of miles of the Pacific. Within this area, you’ll find, moving roughly from northwest to southeast: Tuvalu, Tokelau, Wallis and Futuna, Samoa (formerly Western Samoa), American Samoa, Tonga, Niue, the Cook Islands, French Polynesia (including Tahiti and the Society Islands, the Marquesas Islands, the Austral Islands, and the Tuamotu Archipelago with the Gambier Islands), and Pitcairn Island.

Moai statues on Easter Island, representing Polynesian culture and heritage

Moai statues on Easter Island, representing Polynesian culture and heritage

Understanding where is Polynesia geographically is crucial to appreciating the unique development of its culture. The ancestors of the Polynesians, skilled navigators, arrived in this region approximately 2,000 to 3,000 years ago. They initially settled in the western islands – Wallis and Futuna, Samoa, and Tonga. These islands, while seemingly idyllic, presented significant environmental challenges for early inhabitants. They lacked many resources necessary for human life, requiring the early Polynesians to be resourceful, transporting and cultivating essential plants and domesticating animals. This initial environment profoundly shaped Polynesian culture, fostering innovation and adaptation.

Map of Pacific Islands culture areas, showing Polynesia, Melanesia, and Micronesia

Map of Pacific Islands culture areas, showing Polynesia, Melanesia, and Micronesia

The arrival of European explorers in the late 18th century and missionaries shortly after marked a turning point for Polynesian cultures. Western colonialism brought significant changes. Britain, France, Germany, New Zealand, the United States, and Chile all laid claim to various Polynesian islands. New Zealand was annexed by Britain in 1840, leading to complex interactions with the indigenous Māori population. Missionary influence grew, and Christianity became deeply embedded in Polynesian life, often intertwining with local traditions. Villages frequently competed in constructing grand churches, demonstrating the strong adoption of Christianity within Polynesian societies. Polynesians also played a role in spreading Christianity to other parts of the Pacific, particularly Melanesia.

Following World War II, a wave of decolonization swept through Polynesia. Samoa achieved independence from New Zealand in 1962, becoming the first postcolonial Pacific nation. While some islands, like Tonga, retained monarchies, most Polynesian territories have gained varying degrees of independence. Easter Island stands as a unique case, annexed by Chile in 1888, making its people the only Pacific Islanders under Latin American control. The original culture of Easter Island suffered greatly due to diseases and slave raids in the 19th century, though the indigenous Rapa Nui language persists alongside Spanish.

For over two centuries, Polynesia has captured the Western imagination as a paradise. Early European explorers like Louis-Antoine de Bougainville and Captain James Cook disseminated romanticized images of Polynesian life, further popularized through novels, art, musicals, and films. Works like Herman Melville’s Typee and Paul Gauguin’s paintings contributed to the enduring idea of Polynesia as a blissful, carefree haven. However, traditional Polynesian societies were far more complex and sophisticated than these idealized portrayals, demonstrating remarkable adaptation to their environments.

Contemporary Polynesia reflects both this romanticized image and the realities of colonial impact and cultural resilience. French Polynesia, for example, experienced profound changes due to French nuclear testing from 1966 to 1996 on Mururoa and Fangataufa atolls. This program, while boosting the economy through military presence and infrastructure development, also led to urbanization, a shift from subsistence economies, and long-term environmental consequences. While tourism has become a significant industry since the cessation of nuclear testing, French Polynesia also grapples with the legacy of this period, including pro-independence movements.

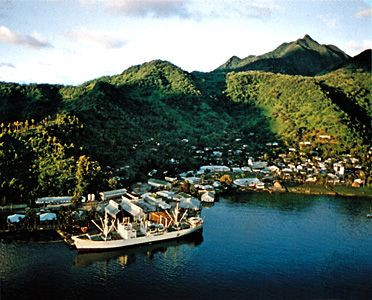

Pago Pago harbor in American Samoa, a modern Polynesian urban center

Pago Pago harbor in American Samoa, a modern Polynesian urban center

Urbanization is a growing trend across Polynesia. Towns like Apia in Samoa, Pago Pago in American Samoa, and Nukuʻalofa in Tonga have drawn populations from rural areas. Migration beyond Polynesia is also significant, with large Polynesian communities in New Zealand, particularly Auckland, and in the United States, especially Hawaii, California, Washington, and Oregon. In fact, for some island groups like Samoa and the Cook Islands, more people live abroad than on their home islands.

Despite these changes, a strong movement to revive and maintain indigenous Polynesian customs and values is evident. Since the 1960s, a flourishing of indigenous Polynesian literature has emerged, particularly from Hawaii, New Zealand, Samoa, and Tonga, exploring themes of identity, colonialism, and cultural heritage. Language revitalization efforts have also gained momentum since the 1970s, with immersion schools for Polynesian languages proving successful in places like New Zealand and Hawaii, contributing to the resurgence of Māori and Hawaiian languages. Languages like Samoan, Tongan, and Tahitian have remained robust.

Festivals play a crucial role in expressing contemporary Polynesian identity. The Festival of Pacific Arts, established in 1972, is a major event for celebrating and perpetuating Pacific arts, music, and dance, held every four years in a different Pacific country. Local festivals like the Heiva in Tahiti, the Teuila Festival in Samoa, and the Merrie Monarch Hula Competition in Hawaii further contribute to cultural preservation and expression.

Traditional Polynesian navigation, a remarkable art form, has also seen a revival. The Polynesian Voyaging Society, founded in Hawaii in 1973, has been instrumental in reconstructing and sailing traditional double-hulled canoes like the Hokule’a, rediscovering and teaching ancient navigation techniques. These voyages serve as a powerful symbol of Polynesian heritage and resilience, inspiring contemporary generations to connect with their cultural roots.

In conclusion, Polynesia is located in the heart of the Pacific Ocean, a vast triangle connecting Hawaii, New Zealand, and Easter Island, encompassing numerous islands and diverse cultures. While facing historical and contemporary challenges, Polynesian people are actively preserving and revitalizing their rich cultural heritage, ensuring that the spirit of Polynesia continues to thrive.