Christianity, a global faith with a following of over two billion people, profoundly shapes cultures and societies worldwide. Its pervasive influence in modern times can obscure its humble beginnings. Understanding where Christianity originated is crucial to grasping its initial development and the factors that molded its core tenets and practices. This exploration delves into the geographical and cultural landscapes that nurtured the nascent stages of Christianity, examining how these environments contributed to its formative beliefs and trajectory.

The Galilean Cradle: Jesus and the Socio-Economic Landscape

To understand the origin of Christianity, it’s essential to begin with Jesus, the central figure of the faith. Jesus hailed from Nazareth, an unassuming village nestled in the Galilee region of northern Palestine. To truly appreciate the genesis of Christianity, we must consider the characteristics of 1st-century CE Galilee during Jesus’s lifetime.

Nazareth and Lower Galilee

Galilee in the 1st century CE was geographically divided into Lower and Upper Galilee. Nazareth and the Sea of Galilee, significant for being the working grounds of several disciples and the location where Jesus called them to follow him, were situated in Lower Galilee, the southern part of the region. Therefore, when investigating Where Did Christianity Originate, Lower Galilee stands out as the primary focal point.

View of Sea of Galilee, Israel

View of Sea of Galilee, Israel

Lower Galilee was marked by two principal urban centers: Sepphoris and Tiberius. Tiberius was strategically located on the Sea of Galilee’s edge, while Sepphoris was inland, merely about 3.5 miles from Nazareth. Historically significant, Sepphoris had been razed by Roman forces during a Jewish revolt around 4 BCE, close to Jesus’s birth, and its reconstruction likely occurred during Jesus’s lifetime.

The Economic Hardships of 1st Century Galilee

The economic structure of Lower Galilee in the 1st century was predominantly agrarian. Sakari Häkkinen highlights that farming was the primary occupation for the vast majority of the population, although a small-scale fishing industry also existed around the Sea of Galilee. Crucially, these farmers were not affluent; approximately 90% lived at a subsistence level, struggling to make ends meet.

John Kloppenborg vividly describes the precarious existence of most Galileans in the 1st century:

One bad harvest or one serious misfortune might mean the loss of everything, since the new patronal class, already viewed with distrust, could not be depended upon for help.

This starkly illustrates the absence of a social safety net. Galilean society offered little to cushion the fall for those struck by economic hardship. This socio-economic vulnerability profoundly influenced the environment in which Jesus lived and taught.

Jesus’ Teachings Reflecting Galilean Life

Considering Jesus’s likely background as a carpenter, as mentioned in the Gospel of Mark, John Dominic Crossan suggests he belonged to the artisan class. This would have placed him and his family at the margins of subsistence, constantly threatened by economic instability. This Galilean context and his socio-economic standing are palpably reflected in his teachings.

Jesus’s parables, for instance, frequently draw from agricultural life. Parables such as the Sower (Matthew 13:1–23, Mark 4:1–20, Luke 8:4–15), the Growing Seed (Mark 4:26-29), the Mustard Seed (Matthew 13:31–32, Mark 4:30–32, Luke 13:18–19), and the Tares (Matthew 13:24-43) are replete with agricultural imagery. This is no coincidence; Jesus primarily preached in Galilee, and his largely agrarian audience would have immediately grasped these metaphors drawn from their daily lives.

Furthermore, several parables touch upon themes of poverty. The Parable of the Workers in the Vineyard (Matthew 20:1-16), for example, portrays a vineyard owner’s seemingly unjust practice of paying all workers the same wage, regardless of their hours. This parable would have resonated deeply with those familiar with economic disparities.

Debt, a persistent burden for the poor, is addressed in the Parable of the Unforgiving Servant (Matthew 18:21-35). In this parable, a servant’s massive debt is forgiven, yet he refuses to forgive a trivial debt owed to him. The lesson of mercy and forgiveness would have been particularly poignant for the debt-ridden poor of Galilee.

In Matthew 6:25-30, Jesus further addresses the anxieties of poverty:

“Therefore I tell you, do not worry about your life, what you will eat or what you will drink, or about your body, what you will wear. Is not life more than food and the body more than clothing? Look at the birds of the air: they neither sow nor reap nor gather into barns, and yet your heavenly Father feeds them. Are you not of more value than they? And which of you by worrying can add a single hour to your span of life? And why do you worry about clothing? Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow; they neither toil nor spin, yet I tell you, even Solomon in all his glory was not clothed like one of these. But if God so clothes the grass of the field, which is alive today and tomorrow is thrown into the oven, will he not much more clothe you—you of little faith?”

For a subsistence farmer in Galilee, constantly on the brink of losing everything, these words would have carried a radical and profound message of hope and trust in divine providence, far more impactful than for a modern, middle-class individual. Jesus’s teachings were undeniably shaped by his 1st-century Galilean environment and the socio-economic realities of his audience.

The Religious Milieu of 1st Century Galilee: Judaism and Synagogues

The religious context of 1st-century Galilee was firmly rooted in Judaism. The majority of Galileans were Jewish, and their religious life was intrinsically linked to the Judaism of that era. While Jerusalem, located in Judea, was the epicenter of Jewish cultic life, housing the Temple and serving as the focal point for major Jewish festivals and sacrifices, religious life was vibrant in Galilee itself. The Temple in Jerusalem was undoubtedly central, and pilgrimages, like Jesus’s to Jerusalem for Passover, were common, but local religious practices were also significant.

Synagogues as Centers of Religious and Community Life

Outside of Jerusalem, the synagogue was the cornerstone of religious life. The term “synagogue” originates from the Greek word meaning “a place of assembly.” Archaeological discoveries provide compelling evidence that synagogues served as more than just places of worship; they were community hubs for discussion and social interaction. As public institutions, synagogues also held political significance, intertwining religious and civic life.

Remarkably, over 50 ancient synagogues have been unearthed in Galilee alone, with the oldest dating back to the early 1st century CE. These archaeological findings underscore the importance of synagogues in the Galilean religious landscape during Jesus’s time.

Jesus’ Synagogue Teachings

The Gospels frequently depict Jesus preaching in synagogues. In virtually every town Jesus visited, including his hometown Nazareth, the Gospels recount that he “entered the synagogue and taught” (Mark 1:21, Matthew 4:23). The synagogue provided Jesus with a ready-made audience, a community already assembled for religious and communal purposes. His choice of synagogues as a primary venue for teaching highlights the Jewish context of his early ministry and the existing religious structures within which Christianity began to take shape.

Having considered the geographic, economic, social, and religious factors shaping 1st-century Galilee, it’s crucial to trace the subsequent spread of Christianity beyond Palestine. The narrative shifts to Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey), where Christianity underwent further development and transformation within nascent communities.

From Galilee to Asia Minor: The Spread and Transformation of Early Christianity

While Galilee served as the birthplace of Jesus and the initial setting for his ministry, Christianity’s expansion and evolution quickly moved beyond the borders of Palestine. The efforts of Paul and other missionaries were instrumental in disseminating the Christian message throughout the Roman Empire, particularly in Asia Minor. This region played a pivotal role in shaping the trajectory of Christianity.

Paul’s Background and Asia Minor’s Greco-Roman Culture

Paul, a key figure in early Christianity, hailed from Tarsus, a city in Cilicia, a region within the Roman province of Asia Minor. After his transformative conversion experience, Paul dedicated his life to preaching and establishing Christian communities across Asia Minor, including in prominent cities like Ephesus, Galatia, Laodicea, and Pergamum, before extending his missionary journeys to Greece. Given Paul’s origins in Asia Minor, understanding this region’s characteristics is vital to understanding his influence on Christianity’s development.

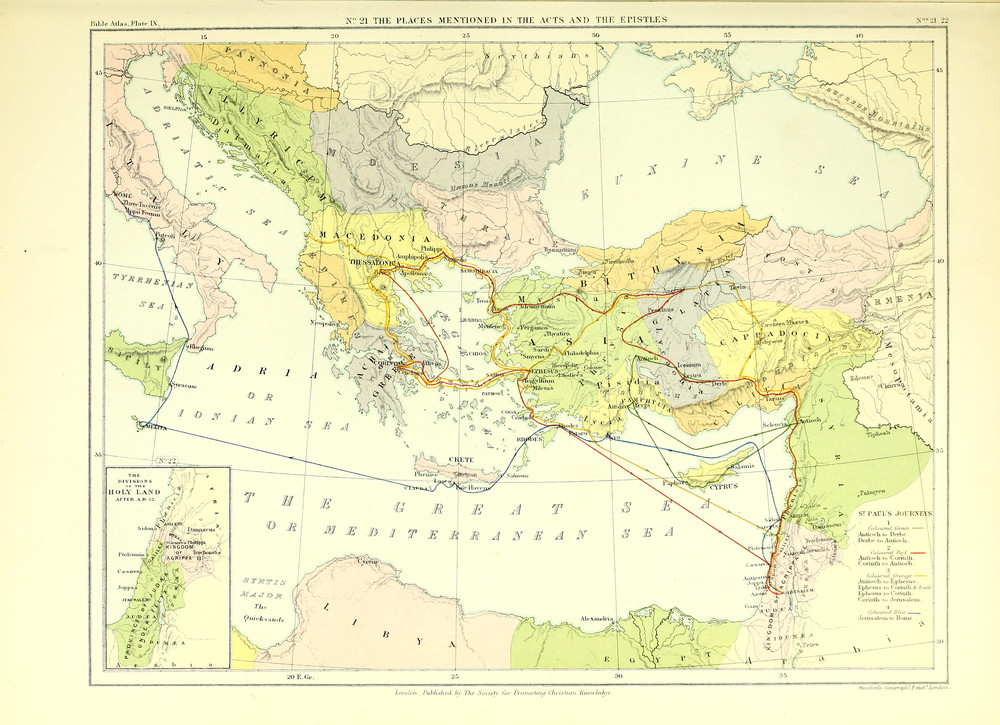

Map of Israel, Galatia, Asia Minor

Map of Israel, Galatia, Asia Minor

Unlike the predominantly rural Galilee, Asia Minor was characterized by its urban culture, boasting several large and influential cities. Asia Minor had a distinct historical trajectory. It was conquered by Alexander the Great and became part of his Hellenistic empire before being absorbed into the Roman Empire. This history imbued Asia Minor with a strong Greco-Roman cultural identity. Greek was the lingua franca, the primary language spoken by most inhabitants, including Paul. Greek philosophy, encompassing figures like Plato, Aristotle, and the Stoics, profoundly influenced the intellectual landscape. Temples dedicated to Greek and Roman deities dotted the urban and rural landscape, reflecting the prevailing religious pluralism.

The Influence of Greco-Roman Thought on Paul’s Theology

Despite his strong Jewish identity, Paul was immersed in Greco-Roman culture from birth. This exposure did not diminish his Jewishness but rather added another layer of perspective absent in the teachings of Jesus and his Galilean disciples. Paul’s background and thought processes differed significantly from those rooted solely in the Galilean context.

Emily Wilson, a classicist, notes Paul’s deep engagement with Stoic philosophy: “Paul was deeply influenced by Stoic philosophy… He borrowed the notions of indifferent things, of what is properly one’s own, the ideal of freedom from passion, and the paradoxical notion of freedom through slavery, fairly directly from the Stoics.”

Scholarly debate continues regarding the extent to which Paul consciously borrowed Stoic concepts or whether these ideas, prevalent in the cultural milieu of Asia Minor, subtly permeated his thinking alongside his Pharisaic Judaism. Regardless, this synthesis of Jewish and Greco-Roman thought marked a significant departure from Jesus’s original teachings.

Paul’s use of the term “spirit” (Greek: pneuma) exemplifies this influence. Troels Engberg-Pedersen points out that contemporary understanding often equates “spirit” with an immaterial, intangible entity. However, Paul’s conception of “spirit” appears to be different.

Engberg-Pedersen argues that for Paul, “spirit” was something physical, albeit highly refined, capable of interacting with the physical world. This concept aligns closely with Stoic notions of spirit as a subtle, pervasive material force. This suggests either direct Stoic influence on Paul or the widespread prevalence of Stoic thought in Asia Minor during his time, both plausible scenarios.

It is crucial to reiterate that Greco-Roman influences did not negate Paul’s Jewish identity. Paul consistently referenced the Hebrew Bible and interpreted Christ’s significance through the lens of Hebrew Scripture. He proudly affirmed his Jewish heritage and adherence to Jewish law, as evident in Philippians 3:6.

If anyone else has reason to be confident in the flesh, I have more: circumcised on the eighth day, a member of the people of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Hebrew born of Hebrews; as to the law, a Pharisee; as to zeal, a persecutor of the church; as to righteousness under the law, blameless.

However, the integration of Greek philosophical concepts into his Jewish faith resulted in a theological framework distinct from that of the Jerusalem Church, potentially contributing to his disagreements with Peter and James in Antioch, as recounted in Galatians 2:11-13.

Urban Context and Paul’s Imagery

Paul’s teachings also reflect the urban Greco-Roman environment of Asia Minor through his use of imagery and metaphors. For instance, in 2 Corinthians 10:3-4, Paul employs military metaphors:

Indeed, we live as humans but do not wage war according to human standards, for the weapons of our warfare are not merely human, but they have divine power to destroy strongholds.

The Roman Empire in the 1st century was perpetually engaged in warfare, expanding or defending its vast territories. References to weapons and warfare would have resonated deeply with audiences in Asia Minor, who frequently witnessed Roman soldiers and military activities. In contrast, Galilee lacked a significant Roman military presence, making such imagery less immediately relevant.

Paul also utilized athletic imagery, drawing from the Greco-Roman tradition of athletic games. The Isthmian Games, akin to the Olympics, were regularly held in Corinth, a city Paul ministered in. In his first letter to the Corinthians, Paul uses athletic competition as a metaphor for the Christian life:

Do you not know that in a race the runners all compete, but only one receives the prize? Run in such a way that you may win it. Athletes exercise self-control in all things; they do it to receive a perishable wreath, but we an imperishable one. So I do not run aimlessly, nor do I box as though beating the air…1 Corinthians 9:24–26

References to running races, boxing, and striving for victory in athletic contests were readily understood within the Greco-Roman cultural context of Paul and his audience. These images, drawn from urban Greco-Roman life, further illustrate the shift in context from the agrarian Galilee to the urbanized Asia Minor in the development of early Christianity.

Asia Minor: The Launchpad for a Distinct Christian Movement

When considering where did christianity start as a distinct movement, the answer points towards Asia Minor. While the seeds of Christianity were sown in the Galilee with Jesus’s ministry and teachings within a Jewish context, it was in Asia Minor that these seeds began to sprout and take on a new form, influenced by the Greco-Roman world. Paul’s missionary work and theological interpretations, shaped by his Greco-Roman environment, played a crucial role in this transformation.

Conclusion

Understanding the history of ideas necessitates acknowledging the profound influence of their geographical and cultural origins. Both location and culture are formative forces that shape human thought and belief systems.

While the foundational narrative of Christian origins is widely known, the specific places where it originated, developed, and spread are often overlooked. So, where did Christianity originate geographically? The Galilee.

Galilee, the birthplace and formative environment of Jesus and his disciples, was a region of striking natural beauty juxtaposed with pervasive poverty. Jesus and his followers likely came from humble backgrounds, possibly experiencing economic vulnerability and hardship. This socio-economic reality undeniably shaped Jesus’s worldview and teachings.

His parables vividly depict the lives of agricultural workers, the ethical dilemmas of landowners and laborers, and the constant anxieties faced by the impoverished. Combined with the social and religious influence of synagogues, these factors contributed to Jesus’s unique interpretation of 1st-century Judaism.

Paul, though deeply committed to Judaism, was also a product of Asia Minor, a Greek-speaking Roman province where he was raised and conducted much of his missionary work. Paul, whether consciously or unconsciously, synthesized faith in the God of Israel with elements of Stoic philosophy and Greco-Roman cultural perspectives. This synthesis resulted in a new religious expression that flourished in Asia Minor and beyond, marking Asia Minor as the crucial geographical and cultural bridge in the transition of early Christianity from its Jewish Galilean roots to a distinct, expanding religious movement within the Greco-Roman world.