The biblical narrative of the Tower of Babel recounts a pivotal moment in early human history, a story widely interpreted as a real event occurring after the global Flood. As humanity, then unified in language and purpose, gathered in one place, they embarked on constructing a city and a tower of immense height, a project interrupted by divine intervention that led to the confusion of languages and the dispersal of people across the earth. For centuries, archaeologists and historians have been captivated by the question: Where Was The Tower Of Babel actually built?

Tradition often places Shinar, the land mentioned in the Bible as the location of Babel, in southern Mesopotamia, with Babylon as the city itself. However, a deeper investigation into historical records, geographical contexts, and geological evidence suggests a different location altogether. This article proposes that Shinar was not in the south, but rather in northeastern Syria, and that the remnants of the Tower of Babel should be sought within the Upper Khabur River triangle, near Tell Brak, a site we identify as the long-lost city of Akkad.

Keywords: Where was the tower of babel, Tower of Babel, Shinar, Erech, Akkad, Calneh, Tell Brak, Tell Fakhariya, Tell Aqab, Khabur River, Mesopotamia, geology of Mesopotamia, Babylon, archaeology, ancient history, Middle East, remote sensing

Unraveling the Mystery of Shinar

Following the biblical Flood described in Genesis 7–8, Noah and his family emerged from the Ark in the Ararat mountains, embarking on a new chapter for humanity in a transformed world. Genesis 11:2 tells us that these descendants of Noah migrated to a plain in Shinar. The Jewish historian Josephus, in his Antiquities of the Jews (1:4:1), corroborates this, stating Shinar as the initial settlement area for the burgeoning post-Flood population. It was in Shinar that humanity, in its unified state, defied God’s command to scatter and instead initiated the ambitious project of building a city and a tower, “to make a name for themselves” (Genesis 11:4). Therefore, our quest to pinpoint where was the Tower of Babel must begin with accurately locating the land of Shinar.

The Enigmatic Name: Shinar

The term “Shinar,” as it appears in Scripture, is often assumed to be the original Hebrew name for this region. However, this assumption may be inaccurate. Shinar was not a land where Hebrew was the primary language. The language spoken in Shinar belonged to the Semitic family, a broad group of related languages that includes Hebrew. These languages, such as Akkadian and Chaldean, as well as Assyrian, Aramaic, and Arabic, shared linguistic roots but possessed distinct spelling variations for place names and words. (For an insightful discussion on ancient Semitic languages, see Rendsburg 2003, pp. 71–73.) These Semitic tongues were prevalent across vast territories of the ancient Middle East.

The diversity within Semitic languages, coupled with the complexities of transcribing ancient writing systems, could explain the numerous spelling variations associated with “Shinar.” These variations include Sanhar (Dillmann 1897, p. 353), Shanhar (Pritchard 1950, p. 247; Zadok 1984), Sanhara (Gemser 1968, pp. 35–36), Sangara, Singara, Sinar, Sanhar, Sangar, Sanar (Albright 1924), Senaar (Brenton LXX), and Sennaar (NETS LXX).1 This list, while not exhaustive, demonstrates the fluidity of place names in the ancient Middle East, where a single location could be referenced under various spellings. We will encounter further instances of Semitic language variations impacting place names throughout this analysis.

The proposed meanings for “Shinar” are remarkably diverse, some interpretations appearing quite tenuous. For example, Ball (1895) proposes a complex linguistic argument suggesting “Shinar” might mean “date palm.” Stinehart (2010) suggests a convoluted interpretation, “with the Hurrian brothers,” based on the premise that Shinar is of Hurrian, not Semitic, origin. An anonymous source (Daniel 1. Living IN the World but not OF the World 2007) claims “Shinar” signifies “to shake out,” linking it to God’s act of dispersing mankind at Babel. Another interpretation (Turanian–Sumerian: Anagram Conspiracy 2009) posits “Shinar” as an anagram created by the Akkadians, referencing a Turkish word meaning “light of glowing fire.” Hislop (1903/2007, p. 137) suggests “Shinar” derives from Hebrew “shene” (repeat) and “naar” (childhood), thus interpreting “Shinar” as “land of the Regenerator.”

However, the most plausible interpretation seems to be that “Shinar” is simply a Semitic form of “two rivers” (in Hebrew, “shene nahar”) (e.g., Rollin 1836, p. 284; Smith 1948, p. 622). Therefore, Shinar would translate to “land of two rivers,” a meaning closely echoing the Greek term “Mesopotamia.”2 This understanding directs our search for Shinar to a region encompassing two significant rivers.

While Shinar is frequently referred to as a land, as evidenced in Genesis 14, where Amraphel is identified as king of Shinar (a figure we will revisit), it may not have always been a clearly defined country with fixed borders. Ancient Middle Eastern kingdoms often lacked permanent boundaries, with territories expanding and contracting based on a city’s power and treaties with neighboring rulers (Ristvet 2008). This contrasts with the divinely ordained, unchanging borders of the Israelite tribal lands (Joshua 12–19), a distinction not always recognized in modern perspectives shaped by defined nation-states.

Shinar’s Biblical Footprint

Shinar appears eight times in the Bible: Genesis 10:10; 11:2; 14:1, 9; Isaiah 11:11; Daniel 1:2; and Zechariah 5:11. Additionally, Achan’s transgression in Joshua 7:21 involved taking a “Shinarish garment” as forbidden spoils from Ai. While the King James Version (KJV) calls it “Babylonian,” the original Hebrew word is the same used for “Shinar” in the other verses (Strong 1894, #8152). The Genesis verses consistently place Shinar as the location of the Tower of Babel. Isaiah 11:11 mentions Shinar in the context of gathering the Israelites from distant lands. Zechariah 5:11 presents a vision where an angel foretells the building of a “house for the ephah” in Shinar.3

The reference to Shinar in Daniel 1:2 is particularly revealing. When Nebuchadnezzar transported vessels from the Temple in Jerusalem to Shinar, “to the house of his god,” it raises the question of location. Given that Nebuchadnezzar was king of Babylon and resided in Babylon, it’s unlikely that Shinar was synonymous with Babylon itself. Had it been, the biblical text would likely have stated so directly, as it does in 2 Chronicles 36:5–7. Instead, Shinar seems to have been a territory within Nebuchadnezzar’s vast kingdom, visited en route back to Babylon. As we will argue, Shinar was largely situated in present-day northeast Syria. The exact location of “the house of his god” in Shinar remains speculative. The biblical author assumed contemporary readers would understand its location without explicit detail. One possibility is that Nebuchadnezzar deposited the Jerusalem booty at a northern temple dedicated to Marduk (or Merodach, Jeremiah 50:2, KJV), also known as Bel, the chief deity of Babylon’s pantheon at that time (Oates 1979, p. 105). Evidence of Marduk worship exists in the north; ancient Ebla in northwest Syria is even called “Tell Mardikh” (a variant of Marduk) today (Finegan 1979, p. 43).

Another compelling possibility is that “his god” refers to Nabu (or Nebo, Ward 1887), the deity in whose honor Nebuchadnezzar was named. Nabu, alongside Marduk/Bel, had gained significant prominence in the north. Dirven (1999, p. 130) notes:

From the eighth century BCE the cult of Nabu is widely attested among the Aramaic-speaking population living in Syria . . . . The god enjoyed great popularity . . . particularly in northern Syria.

Furthermore, Edessa, an ancient Turkish city now known as Sanliurfa or Urfa (Grant 1997, p. 229), counted Nebo among its primary deities from very early times. Drijvers (1980, pp. 40–75) states, “Nebo holds the first place and evidently is Edessa’s most venerated god.” Sanliurfa lies on a plain approximately 50 km (31 miles) north of Harran, just north of the Turkish-Syrian border, east of the Euphrates River (Heritage 2004, p. 143). Sanliurfa’s location places it within the broader region of Shinar, making it a potential candidate for the “house of his god” where Nebuchadnezzar might have left the temple vessels.

It is important to note that Nebuchadnezzar did transport some temple vessels back to Babylon city on a later expedition (2 Chronicles 36:5–7). The Bible describes two distinct campaigns against Jerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar: the first in Jehoiakim’s third year (Daniel 1:1) and the second after Jehoiakim’s 11-year reign (2 Chronicles 36:5). Misunderstanding this detail leads some to incorrectly claim that Daniel 1:2 proves Shinar encompassed Babylon city (as argued by Albright 1924). A third plundering of Jerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar is detailed in 2 Kings 24:13 during Jehoiachin’s reign, where he seized all remaining temple and palace treasures, including large items likely cut up for transport, such as pillars, the sea, and bases mentioned in Jeremiah 27:19.

These temple vessels reappear later when Belshazzar, in Babylon city, held a banquet and ordered them brought out for his guests (Daniel 5:2–3). Ezra 1:7–8 recounts King Cyrus returning these vessels, taken by Nebuchadnezzar from Jerusalem, to Sheshbazzar, the prince of Judah, after issuing a decree allowing exiles to return to Jerusalem and rebuild the Temple (Ezra 1:1–6). Ezra 1:7 (KJV) states Nebuchadnezzar had placed this treasure “in the house of his gods,” while Brenton and NETS LXX use “house of his god.” If “his god” was Nabu, as suggested, a major temple dedicated to Nabu existed at Borsippa, only 18 km (11 miles) southwest of Babylon city (Borsippa 2010), potentially the repository for this portion of Jerusalem’s treasures. However, the text doesn’t specify the fate of the temple booty initially taken to Shinar, nor whether all vessels originated from Babylon city. It is conceivable that the Shinar portion was included in the count and returned to Jerusalem with exiles from the northern region.

It is crucial to distinguish whether biblical and historical references to “Babylon” denote the city or the kingdom of Babylon.

Many biblical verses mentioning Babylon could refer to the broader kingdom, not just the city. Isaiah 39:6–7 foretells the carrying away of all in the king’s house to Babylon, but the chapter’s context suggests “Babylon” represents the kingdom. Similarly, in Ezra 6:1, 2, Darius orders a search for Cyrus’ decree to rebuild the Jerusalem temple “where the treasures were laid up in Babylon.” The scroll was found in Achmetha (Ecbatana, Hamadan), the Median capital (modern Iran), far from Babylon city, though Media was part of the Babylonian kingdom at the time (Heritage 2004, p. 148; Yamauchi 1990, p. 305). This location is logical as Ecbatana was Cyrus’ summer capital, where he might have issued the decree (Mitchell 1991, pp. 426–427).

In another example, a Babylonian account of a Hittite campaign by Mursili I mentions an attack on “Shinar” (Sa-an-ha-ra), while a Neo-Hittite document describes the same campaign as against “Babylon” (Kalimi 2000, p. 1213). This suggests that Shinar was considered a distinct territory in one account, but part of the Babylonian empire in another. Given the Hittite kingdom’s northern location (modern-day Turkey, Hittite Period, 2006), Shinar would have been geographically closer and a more logical target for a campaign.

However, the prevalent scholarly assumption that Shinar is the region around Babylon city in the south has led to a circular argument, where biblical texts mentioning Shinar are often interpreted as referring to Babylon city, reinforcing the initial assumption.

Traditional vs. Alternative Locations for Shinar

Genesis 11:2 (KJV) states Noah’s descendants migrated “from the east” to reach the plain of Shinar. However, a survey of 14 translations of Genesis 11:2 reveals an even split between “eastward” and “from the east” (Parallel Translations 2010), with both Brenton and NETS LXX translating “from the east.” These translations imply an east-west relationship between the Ark’s landing place and Babel.

Conversely, the New American Bible reads, “While men were migrating in the east” (Genesis 2009), and the Good News Translation states, “As they wandered about in the east” (Compare Translations 2010). These latter translations conveniently bypass geographical issues by not specifying a direction of migration. Faber (1816, p. 374) cites ancient sources supporting this interpretation. Regardless of translation, the entire migration would have occurred eastward of Israel.

The map of Mesopotamia (fig. 1) clearly shows that Babylon lies hundreds of kilometers directly south of both Mount Cudi and Mount Ararat,4 regardless of which mountain is considered the Ark’s landing site. Fraser (1834, pp. 217–218) and others have noted this geographical discrepancy. This inconvenient fact for those placing Babel in Babylon is often minimized, requiring convoluted scenarios to reconcile scripture with the southern location. One such explanation involves Noah’s family migrating eastward into Iran, then southward, and finally westward back through mountains towards Babylon (Faber 1816, pp. 372–376). Ark enthusiast Cornuke (2008) proposes a different solution by searching for the Ark on Iranian mountains, suggesting a southward and westward migration through mountains to Babylon.

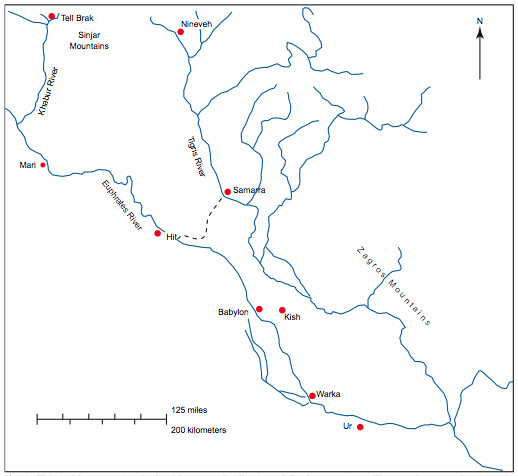

Figure 1

Figure 1

Fig. 1. Mesopotamia, the land between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, is predominantly in Iraq, with small portions in Syria (upper left) and Turkey (northernmost area, partially off-map). Shinar was located in northern Mesopotamia in biblical times; the Khabur triangle (fig. 3) is in the top left corner. The dotted line represents an ancient shoreline, separating north and south. The Tigris and Euphrates merge in the bottom right to form the Shatt al Arab, flowing into the Persian Gulf (Iraq 2003).

However, the overwhelming consensus, both biblical and secular, places Shinar in southern Mesopotamia (southern Iraq) (e.g., Levin 2002; Stewart 2003, pp. 40–41; Walton 1995). Consequently, the traditional view equates Babel, the Tower’s location, with Babylon, the infamous city, believing them to be geographically the same (Benner 2006; Bromiley 1979, p. 382; Brown, Driver, and Briggs 1907, p. 93; Cheyne 1899, pp. 409–412; Henry 1992, p. 25; Kidner 1967, pp. 110–111; Kitto 1904, p. 84; Leick 2002, p. 245; Mackintosh 1972, pp. 56–58; Oates 1979, p. 60; Ross 1985, p. 44; Smith 1948, p. 71). Cooper (1995, p. 177) even suggests an ancient meaning of Babel/Babylon as “the place of canals,” proposing Babel/Babylon also meant “the place of division” or “the place of Peleg.” Halley (1965, p. 83) posits that those remaining in Babylonia after the Tower’s construction halt eventually completed it, forming the nucleus of Babylon city. Creationist Holt (1996) accepts a southern Shinar, arguing its low elevation is significant in determining the Flood/post-Flood geological boundary. Lasor (1988, p. 481) acknowledges conflicting evidence but ultimately concludes Shinar was likely in the south.

Some scholars propose a compromise, suggesting Shinar initially referred to a northern Mesopotamian region, later expanding to include the south (Fraser 1834; Rollin 1836). Wells (1820, pp. 114, 133) defines Shinar as a north-south valley along the Tigris, from Turkey’s “Armenian” mountains to the Persian Gulf, accommodating both northern Sinjar mountains (linked to “Shinar”) and southern Babylon as Babel.

Alternative southern locations for the Tower have been proposed, arguing “Babylon” was a title applied to multiple cities (Dalley 2008). Birs Nimrud at Borsippa, southwest of Babylon, is a candidate, its name even containing “Nimrod” (Halley 1965, p. 83; Jones 1897, pp. 3–4; Lowy 1893, pp. 229–230). Eridu in southern Mesopotamia is another contender, citing its age, large ziggurats, and shared temple names with Babylon (e.g., Esagila) (Rohl 1998, pp. 222–223).

For a period, scholars equated Shinar with Sumer (southern Mesopotamian Sumerian territory) (e.g., Hastings, Davidson and Selbie 1902, pp. 503–504; Jastrow 1915, p. 3), attempting linguistic equivalences (e.g., Barton 1923). This equation conveniently placed Shinar in the south, aligning with the traditional Babel location (Potts 1997, p. 43). While some, like van der Toorn and van der Horst (1990), remained ambivalent, and Zadok (1984) argued against Sumer-Shinar derivation, the Sumer-Shinar connection persists (see Aling 2004; Koutoupis 2009).

The theory identifying Amraphel of Genesis 14 with Hammurabi, the sixth king of Babylon’s First Dynasty (Pinches 2010), was once popular. If Amraphel was Hammurabi, and Amraphel was king of Shinar, then Shinar must be Babylon. However, this identification faces significant challenges. Albright (1924) highlights linguistic difficulties in equating Amraphel and Hammurabi, despite both names being Amorite. Chronological inconsistencies also arise. Biblical chronology places Amraphel in Abraham’s time, around 1900 BC (Jones 2007, p. 24), after Abraham’s Canaan migration. Hammurabi’s reign dates are debated, ranging from 2300 BC (Goodspeed 1902, p. 109) to 1700–1900 BC (Oates 1979, p. 24) in secular scholarship, and even as late as the 16th century BC (Velikovsky 1999) based on Cretan archaeological evidence (Nilsson 1928, p. 385; Pendlebury 1930, p. 4).5 These dates suggest Hammurabi reigned centuries after Amraphel, undermining their identification. Some attempts to align Hammurabi with David and Solomon in the 10th century BC (Hickman 1986) are considered unlikely. Therefore, the Amraphel-Hammurabi link is weak.

Early dissenting voices challenged the southern Shinar location. Fraser (1834, pp. 216–217), referencing Beke (1834, pp. 24–26), deemed placing Babel in Babylon “an erroneous notion,” as Ararat would then be north, not east, of Babel. Albright (1924) later argued Shinar was the northern Syrian kingdom of Hanna, bordering the Euphrates. Gemser (1968, pp. 35–36) considered “Sanhara” a major northern Syrian power post-Mari. We will further explore the northern Shinar location later.

Some have proposed entirely different locations for the Tower. Wyatt, believing the Ark was at Durupinar near Ararat (Fasold 1988, pp. 3–10), located the Tower on the Euphrates north of Harran (Wyatt 1995; Ron Wyatt 2010), now submerged by the Ataturk Dam (Ataturk Dam 2010). (See Wyatt n.d. for a map). Sanders, based on NASA photos and biblical texts, proposed the southern Black Sea coast (Grimston 1999). Setterfield (2010) suggests Shinar in Sudan, Africa, citing a place called Sennar/Sinnar between the White and Blue Niles, a “land of two rivers” with a northern region called “El Gezira” (“the island” in Arabic) (East Africa 2004, p. 82; Northern Africa 1962, p. 121; Sennar 1911; Sennar, Sudan 2009). The geographical similarity to the northern Syrian/Iraqi El Jazira is striking, suggesting the African Sennar is named after the Mesopotamian one.

While this article treats the Tower of Babel story as literal history, many believe it was inspired by southern Mesopotamian ziggurats, written later. Woolley (1928, p. 142) called Babylon’s ziggurat “the ‘tower of Hebrew legend’.” Parrot (1955, p. 17) and Siff (2006) also identify the Etemenanki ziggurat in Babylon’s Esagila temple complex as the inspiration, a view they claim is widely accepted, thus placing Shinar in southern Mesopotamia.

Differentiating Babel from Babylon

As noted, some sources place Shinar in northern Mesopotamia, contradicting the majority view. If Babel and Babylon are indeed the same, as commonly believed, then Shinar’s northern location becomes problematic. But is Babel necessarily Babylon? Examining the names “Babel” and “Babylon” is crucial.

The meaning of “Babel” is explicitly given in Genesis as “confound” (Genesis 11:9 KJV), meaning “confuse” (Webster 1973, p. 383). A straightforward reading and sound hermeneutics support this meaning (Habermehl 1995, pp. 5–18). The Septuagint translations (NETS and Brenton LXX, Genesis 11:9) even translate the place name as “Confusion,” not “Babel.”

Oates (1979, p. 60) provides the history of “Babylon”:

The name Babylon—Akkadian Bab-ilim . . . ‘gate of god’—was long thought to be merely a translation of an earlier Sumerian name Ka-dingirra. But the city’s name is first found in the Akkadian form Bab-ilim, now believed to be a secondary spelling developed by popular etymology from an earlier name Babil, the meaning of which is unknown (Gelb 1955). Much later, the plural form Bab-ilani, ‘gate of the gods,’ is found.

The modern name “Babylon” derives from the Greek form of Bab-ilani. Interestingly, Babylon’s ruins are now called Babil (Leick 2002, p. 245).

This analysis reveals that “Babylon” and “Babel” have distinct linguistic origins and meanings (“gate of the gods” vs. “confusion”). Those who equate “Babel” with “Babylon” (e.g., Smith 1948, p. 71; Yates 1962, p. 16) are therefore mistaken.

In the biblical Masoretic manuscript, “Babel” and “Babylon” appear identical in Hebrew as BBL (for Hebrew letters, see Brown, Driver and Briggs 1907; Strong 1894, #894). Ancient Hebrew Old Testament script used only consonants, with vowels pronounced contextually. Vowel markings emerged later, in the Christian era (Mitchell 2005). Words with identical consonants were distinguished by context and vowel pronunciation. Thus, both Babel and Babylon (originally “Babil”) were written BBL. English translations differentiate them, rendering BBL as “Babel” in Genesis 10:10 and 11:9, and subsequently as “Babylon” (260 times). However, the shared BBL spelling is a linguistic coincidence.

The Hebrew noun for “confusion” was balal (Benner 2006), raising the question of why “Babel” (BBL) is used, not the expected BLL. The answer is that “Babel” is likely not Hebrew. Like “Shinar,” “Babel” is probably a Semitic word from the Shinar region. The Aramaic word for “confusion” is balbel (Yates 1962, p. 16), illustrating Semitic linguistic similarities. “Babel” was likely the name used by Shinar’s Semitic inhabitants at the time of the Old Testament’s final editing;6 while related to Hebrew, their language and place name spellings wouldn’t perfectly match Hebrew. (This also explains the Hebrew verb balal for “confounding” in Genesis 11:9, as the narrative itself is in Hebrew.)

Modern scholars and theologians, often conflating “Babel” and “Babylon” due to their shared BBL spelling in Hebrew, attempt to reconcile “confusion” and “gate of the god” as meanings for the same word. The common explanation is a “play on words” (e.g., Ross 1985, p. 44; Yates 1962, p. 16). Harrison (1963, p. 89) claims Babylon is “the Greek form of the Hebrew word ‘babel,’ which was closely allied to, and probably derived from, the Akkadian ‘babilu’ or ‘gate of God,’” omitting “confusion.” Howard (2009) controversially suggests “Babel” meant “the door of God,” confusing the issue further. Jordan (2007, pp. 99–100), citing Hirsch (1989, p. 212f), proposes babel should be read as yabal (wither), linked to balal (confound), suggesting a religious division at Babel leading to the withering of false religions and eventual scattering. This interpretation deviates significantly from a straightforward scriptural reading.

Our conclusion is that Babel and Babylon are distinct places, not necessarily geographically close. Babylon’s ruins, called Babil, are near modern al Hillah (Hilla), southern Iraq, about 80 km (50 miles) south of Baghdad (Iraq 2003). This leaves open the question of where was the Tower of Babel in Shinar actually located, given it wasn’t in Babylon. Given the common belief that Babel must be in southern Mesopotamia, we will first examine that region’s geological suitability.

Geological Challenges to Southern Mesopotamia as Babel’s Location

The geology of southern Iraq is often overlooked by biblical scholars, though some exceptions exist. Fraser (1834, pp. 217–18), citing Nearchus (c. 360–300 BC) and Pliny (AD 23–79), argued post-Flood lower Mesopotamia was uninhabitable and Babylon’s site was underwater. Beke (1834, pp. 17–24) echoed this. Boscawen (1903, pp. 4–5) linked lower Mesopotamia’s ancient submersion to the “myth of the Deluge.” We argue that Babylon’s site, and much of southern Iraq’s alluvium, might have been submerged during the Tower of Babel’s construction period.

Post-Flood, global sea levels were higher. The ensuing Ice Age, likely caused by post-Flood conditions, drew moisture from warm oceans to form continental ice sheets, drastically lowering sea levels.7 Ice melt at the Ice Age’s end raised sea levels back to approximately present levels. Creationist models estimate the Ice Age, including build-up and melt, lasted about 700 years (Oard 2006). Secular geologists propose vastly longer timescales for multiple ice ages and interglacials (Cattermole and Moore 1985, p. 197; Imbrie and Imbrie 1979; Muller and MacDonald 2000; Ray 1999).

If all current land ice melted, sea levels would rise to approximately post-Flood levels.

However, not all ice melted. Remaining ice in Antarctica and Greenland suggests that complete melting would raise sea levels to near post-Flood levels (Genesis 8:13). Current estimates suggest a 70–80 m (229–262 ft) sea level rise if all land ice melted (Alley et al. 2005; U.S. Geological Survey 2000).

A significant geological feature in Iraq, an east-west escarpment from the Euphrates to the Tigris north of Baghdad (Ramadi to Samarra), stands 6–15 m (19–49 ft) high at about 76 m (249 ft) altitude. This ridge is considered an ancient shoreline (Boesch 1939; Guest 1953; Held and Held 2000, p. 337; Lloyd 1955, pp. 16–17, 29; Maisels 1993, p. 87). Its altitude aligns with the estimated 70–80 m (229–262 ft) sea level rise from melting all land ice.

Fig. 1 shows this feature, described by Ragozin (1893, p. 1) as “a pale, undulating line,” and by Held and Held (2000, p. 337) as “a sinuous cliff, probably the feature for which Iraq is named,” dividing Iraq into the northern desert/rocky al Jezirah (“the island”) and the southern alluvial delta (Aqrawi, Domas, and Jassim 2006, p. 22; Johns 1913, p. 13; Potts 1997, p. 2 map). Rawlinson (1885, p. 3) described this cliff:

But nature has set a permanent mark, half way down the Mesopotamian lowland, by a difference of geological structure, which is very conspicuous. Near Hit on the Euphrates, and a little below Samarah on the Tigris, the traveller who descends the streams, bids adieu to a somewhat waving and slightly elevated plain of secondary formation, and enters on the dead flat and low level of the mere alluvium. The line thus formed is marked and invariable; it constitutes the only natural division between the upper and lower portions of the valley; and both probability and history point to it as the actual boundary between Chaldaea and her northern neighbor.

Iraq experienced no Ice Age ice sheet cover, so crustal rebound isn’t a factor in shoreline height interpretation (Lambeck et al. 2000, p. 517). Most of Iraq (excluding the northeast) is within the Stable Shelf (Jassim and Buday 2006, pp. 57–70), minimizing uplift or subsidence. This ancient geological feature likely marks the post-Flood shoreline before Ice Age ice formation.

However, the southern Iraqi alluvium, a delta formed by Tigris and Euphrates sediments washed down from Turkish mountains and Zagros mountains during Ice Age meltwater runoff (Aqrawi Domas and Jassim 2006, pp. 22, 185–189; McIntosh 2005, pp. 8–9; Nutzel 1979; Persian Gulf Once Dry, Green, and Inhabited by Humans 2007),8 wouldn’t have existed yet during Babel’s construction.

Ice Age meltwater volume is evidenced by glaciers larger than today’s remnants in Turkey, Kurdistan, and northeast Iraq (Kurter 1988, p. G2; Sarikaya, Zreda, and Çiner 2008; Wright 2004, pp. 215–216). Central Turkish glaciers were massive, with moraines kilometers long and hundreds of meters high (Çiner 2004, pp. 423–424).

Pre-Ice Age southern Iraq was a deeply folded northwest-southeast trough from Zagros Mountain formation (Larsen and Evans 1978; Master 2002). Quaternary (Ice Age and later) deposit depth varies due to this trough’s shape. Al Hillah (near Babylon) is near the trough’s edge, with only ~30 m (98 ft) of alluvium, compared to ~270 m (886 ft) depth 200 km (656 ft) southeast (Aqrawi, Domas and Jassim 2006, p. 187, fig. 15-2). Al Hillah’s current altitude is 26 m (85 ft) (Al Hillah 2010), suggesting pre-Ice Age terrain ~4 m (13 ft) below current sea level. Therefore, the Babylon area might have been 76 + 4 = 80 m (249 + 13 = 262 ft) below the original post-Flood sea level. (This trough also contradicts Genesis 11:2’s description of a “plain.”)

While the Babylon site was likely submerged, the exact water depth during Babel’s construction is uncertain. Factors like the time elapsed between the Flood and Babel’s construction, the onset and rate of sea level drop due to ice formation are unknown.

The Ussher chronology places 106 years between the Flood and Babel dispersion (Ussher 1658, pp. 21–22). For Babel to be in Babylon, within 106 years: sea levels would have had to drop >80m, Babylon’s land dry enough for construction, a 600 km southward migration occur, Tower construction begin, and the dispersion happen. This timeline seems highly improbable.

The LXX chronology allows 531 years, but current creationist Ice Age models don’t fit this timeline. Ice buildup would have been complete by Babel’s time, with melt already starting, contradicting Neanderthal evidence from thick ice regions (Habermehl 2010). A different Ice Age model with a longer pre-glacial maximum period would be needed for the LXX timeline, but none currently exists.

Based on geological considerations, the Babylon site was likely underwater, possibly significantly so, during the Tower project. Further detailed analysis is beyond this article’s scope.

Why a Northern Mesopotamian Babel Makes Sense

Modern Iraq maps provide a crucial clue to Shinar’s northern location: the Sinjar Mountains west of Mosul (fig. 1). Mosul is across the Tigris from Nineveh’s ruins. The “Sinjarish formation” of these mountains is geologically recognized (Kennedy and Lunn 2000). The Sinjar name itself prompted this article’s investigation into Babel’s location. However, scholars have resisted linking “Sinjar” to “Shinar” due to their conviction that Shinar couldn’t be in northern Mesopotamia (e.g., Fraser 1842, pp. 96–97). Smith (1893, p. 1281) expressed doubt about any connection between “Shinar” and Singara/Sinjar, an opinion that has persisted.

Figure 2

Figure 2

Fig. 2. The Shinar plain’s flatness is evident in this Khabur River photo south of Al Hasake city, near Tell Sheikh Hamad, North Syria. The Khabur triangle, the upper river section, is slightly north of this point. Photo by Bertramz (Khabur River 2010).

Historically, Shinar was considered a northern territory, equivalent to Sinjar (e.g., Albright 1924; Gemser 1968 pp. 35–36; Graham 1859, p. 72; Sayce 1895, p. 68). Fletcher (1850, pp. 91–92) cited the Egyptian Karnak tablet placing Saenkara (Shinar) near Cappadocia in Turkey, a northern location “which would hardly apply to a territory south of Mosul.” Gelb (1937) stated, “The localization of Shanhar in North Syria, however, seems to be proved beyond any reasonable doubt.” Older texts occasionally refer to North Mesopotamia as Shinar (Bostock and Riley 1893, p. 444f). Ancient Greeks understood Shinar as only northern Mesopotamia (Rollin 1836, p. 284; Goodspeed 1902, p. 4). Hogg (1911, p. 180) stated:

In view of historical and geographical facts there is much to be said for applying the name Mesopotamia to the country drained by the Khabur (River), the Belikh (River), and the part of the Euphrates connected therefore.

Historical evidence points to Shinar as a northern Mesopotamian territory, in Syria and Iraq, between the Euphrates and Tigris. Given the distinct origins of Babel and Babylon, there’s no need to extend Shinar southward.

Precisely defining Shinar’s ancient boundaries is difficult, as they likely fluctuated. However, we generally define Shinar as the region south of the Turkish mountains, between the Tigris and Euphrates. This area is remarkably flat (fig. 2), fitting Genesis’ description of “a plain in the land of Shinar.”

Earlier, we noted Shinar’s likely Semitic origin. Semitic languages have been spoken in this region since antiquity: Akkadian (from 3000 BC, secular timeline), Aramaic (from the 2nd millennium BC), and Arabic (from the 7th century AD) (Akkad 2000; Aramaic 2008; Killean 2004). This supports “Shinar” meaning “Two Rivers.”

We now examine this northern Syrian/Iraqi region for clues to the Tower and city’s remnants.

Erech, Akkad, and Calneh: Keys to Babel’s Location

Genesis 10:10 states Nimrod’s Shinar kingdom comprised Babel, Erech, Akkad,9 and Calneh. These cities, possibly founded by Noah’s sons, retained their association with Nimrod’s original kingdom through to Scripture’s final editing. Babel appears to have been the capital, the center of religion and governance. Leaders and priests likely resided in Babel (post-construction), with the populace in the other three cities. We can envision Babel, Erech, Akkad, and Calneh clustered relatively close in Shinar’s plain, perhaps with Babel centrally located.

We expect to find three tells,10 occupied or not, reasonably close to Babel and each other, with at least one major tell (Akkad). Bonomi’s (1853, p. 42) 210 km (130 miles) city separation, or Jones’ (1897, p. 51) Vermont-New Hampshire-sized kingdom, based on southern Mesopotamian assumptions, are unlikely.

Let’s examine each city, starting with historically significant Akkad, then Erech, and finally Calneh.

Akkad: The Missing Metropolis Found?

Akkad is mentioned only once in the Bible, Genesis 10:10, but is historically significant as Sargon I’s capital (Akkermans and Schwartz 2003, p. 278). Its prominence led Babylonian kings to use the title “King of Akkad” for a millennium after its fall (Leick 2002, p. 85).

Sargon’s Akkad is traditionally placed in southern Mesopotamia, north of Sumer (Johns 1913, p. 14; Oates 1979, p. 11; Ragozin 1893, p. 1; Weiss 1975), possibly near Baghdad (Arnold 2004, p. 23), south of the geological ridge separating northern and southern Mesopotamia.

Despite Akkad’s historical importance, archaeologists have never found it in southern Mesopotamia, despite extensive searches. This Akkadian capital seems to have vanished archaeologically (Leick 2002, p. 85). Evidence for Akkad’s existence only emerged in the late 1800s with cuneiform tablet discoveries (Wall-Romana 1990). (Genesis 10:10’s mention apparently wasn’t considered proof.)

Akkad’s absence may be explained by its northern location. Shinar was in northern Mesopotamia, and Akkad was in Shinar. Therefore, we should seek Akkad in the north, despite prevailing archaeological views. Akkad’s site should be an ancient tell displaying remnants of government buildings, palaces, temples, etc., fitting a royal Akkadian capital.

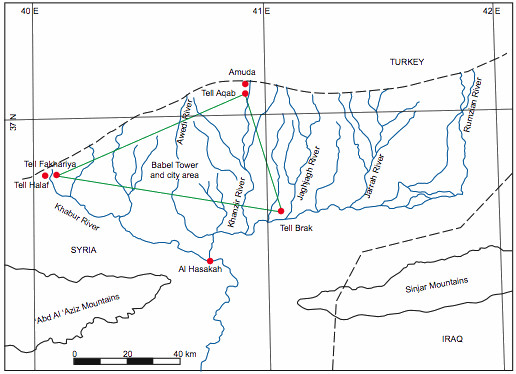

Figure 3

Figure 3

Fig. 3. The Khabur triangle in northeast Syria, named for the upper Khabur River and its tributaries. This article proposes Tell Aqab (near Amuda), Tell Brak, and Tell Fakhariya as Erech, Akkad, and Calneh, respectively. Babel, the capital, would likely be within this triangle.

The prime, and essentially only, northern candidate for Akkad is Tell Brak (or Birak), on the Wadi Jaghjagh11 (figs. 1 and 3). Brak is a vast ancient tell with a fortified “palace” built by Sargon’s grandson Naram-Sin (Kolinski 2007; Oates 2004; Oates and McMahon 2008a). Akkadian structures at Brak are usually explained as a northern outpost of Akkad, a provincial capital (Leick 2002, p. 102; Weiss 2003, p. 20) or “autonomous urban center” (Heinz 2007). This article contends that if archaeologists weren’t fixated on a southern Akkad near Babylon, they would recognize Tell Brak’s suitability as Sargon’s capital. Akkad hasn’t been found because it’s been sought in the wrong location, hiding in plain sight as Tell Brak, like Poe’s purloined letter (Poe 1845). (The name “Brak” even subtly echoes “Akkad.”)

Tell Brak also exhibits pre-Sargonic history in its layers, consistent with a city that rose to prominence ~4,000 years ago. Historian Johns (1913, p. 38) notes about Akkad:

The impression its power made upon the national imagination was so striking that we must postulate a long period of prosperity for the accumulation of the necessary material resources. It cannot have owed its sudden overwhelming supremacy to a fortuitous combination of political or economic causes: it must have long awaited an opening before it marched to empire . . . .

While some historians argue Sargon founded Akkad as a small settlement (Kuhrt 1995, pp. 44–45), Tell Brak’s pre-Sargonic layers disprove this.

Archaeologists acknowledge Tell Brak’s pre-Akkadian (pre-Sargon) importance, identifying it as ancient Nagar (Oates and McMahon 2008a). However, on-site evidence for Nagar-Tell Brak identification is limited. Nagar’s famed goddess Belet-Nagar’s temple hasn’t been found at Brak. Nagar also continues to be mentioned after Akkad’s prominence (Ebeling, Meissner, and Edzard 2001, pp. 74–77; Oates 2004), suggesting Nagar might be a separate mound if Brak is Akkad. Ancient city identification often relies on scholarly consensus more than concrete evidence. Vaux (1855, p. 12) honestly stated, “Hardly any evidence, except the reading of the names on bricks or monuments found in the respective localities, can be deemed a satisfactory proof that the ancient site has really been discovered.” This remains largely true today. “Probably” becomes “is identified with,” eventually becoming simply “is.” This likely explains Tell Brak’s current identification as Nagar; online searches for “Tell Brak and Nagar” readily equate the two (e.g., Eidem and Warburton 1996; Michalowski 2003; Oates and McMahon 2008a).

Tell Brak’s location in the Khabur river triangle12, central to the east-west route from the Mediterranean to Assyria (Semple 1919; Wright et al. 2007), was strategically vital. Sargon’s grandson, Naram-Sin, claiming “King of the Four Corners of the Universe” (Spielvogel 2008, p. 9), reflects Brak’s central position in the known world.

While Tell Brak lacks significant water flow today, the nearby Wadi Jaghjagh and Khabur River had greater flow in Sargon’s time (Wilkinson 2007; Blackburn and Fortin 1994; Herz and Garrison 1998, pp. 24–25), relevant to mentions of Akkad’s wharf for distant trade (Stieglitz 1987, p. 45).

The Akkadian Empire’s sudden collapse around 2200 BC (secular timeline) might also support a northern Akkad. A ~300-year drought began then, believed to have contributed to the empire’s demise (Kerr 1998; Ristvet and Weiss 2005). Northern Mesopotamia was severely affected, with population migration south (Weiss et al. 1993). Placing Akkad in the north better explains its drought-related collapse.13 “The Curse of Akkad,” describing famine due to Naram-Sin angering gods, once considered fictional, is now re-evaluated in light of drought evidence (The Cursing of Agade 2006).

Akkad, despite its power, isn’t mentioned in 1st millennium BC biblical prophecies as it had declined to a minor cult center by then (Kuhrt 1995, p. 45).

Excavations at Tell Brak and elsewhere in north Syria, north Iraq, and southeast Turkey are prompting reassessment of the traditional view that civilization originated in southern Mesopotamia and spread north (Huot 1992; Sanders 2002; Van de Mieroop 1999, pp. 28–31; Wells 1922, p. 52). Brak’s advanced civilization suggests a need to rewrite history, placing early urban development in the north (Crawford 2004, pp. 115–129; Lawler 2009; Oates 2004; Oates et al. 2007). Göbekli Tepe, a remarkably ancient and advanced northern Mesopotamian site near Sanli Urfa (~215 km northwest of Tell Brak), further challenges secular narratives. This temple complex, dating to the Ice Age’s end, predates known sites and defies evolutionary origin models (Symmes 2010).

Secular archaeology’s focus on linear cultural evolution, from primitive to civilized, stems from an evolutionary worldview (Moore 1988). Creationists, with a different historical perspective, assume early post-Flood civilizations were advanced, with “primitive” cave dwellers emerging post-Babel during the Ice Age (Oard 2004, pp. 127–129).

Southern Mesopotamia’s low elevation and post-Ice Age alluvium likely made it less habitable initially than the north. Earlier northern civilization development makes geological sense. However, the “south-first” civilization idea is deeply entrenched.

We conclude that Akkad, the first of Babel kingdom’s trio of cities, is likely Tell Brak in north Syria.

Erech: Uruk of the North?

Erech is mentioned once in Genesis 10:10. (Brenton and NETS LXX spell it “Orech.”) Ezra 4:9 mentions men from Erech or Uruk (KJV “Archevites,” LXX “Archyaeans”), part of the Babylonian empire’s transplanted populations in Samaria (Ezra 4:10).

Secular and biblical historians equate “Erech” with “Uruk,” both names for modern Warka in southern Iraq (Duncan 1915; Fischer 2008, pp. 53–54; Leick 2002, p. 30; Loftus 1857, pp. 160–161). This complicates finding biblical Erech, as Erech/Uruk references could be either northern Shinar (near Tell Brak/Akkad) or southern Warka. The Archevites of Ezra 4:9 could be from either location.

Historical indications suggest a northern Syrian city in the Khabur triangle as biblical Erech. “Urakka” appears in Assyrian sources (Astour 1968, 1993; Olmstead 1921; Postgate 1974). Urakka is shown on the Assyrian Empire map (Parpola 1987) near Amuda, Syria, close to the Turkish border (fig. 3). Tell Aqab, 6 km (3 miles) south of Amuda, could be Urakka; excavations show ancient origins (Davidson and Watkins 1981). Etymologically, removing “Ur” from “Urakka” yields “akka,” close to “Aqab,” making the equation plausible.14 “Arakdi” appears to be another spelling variant, located north of “Til Bari” (Tell Barri, ~10 km north of Tell Brak), considered significant in the 9th century BC (Olmstead 1918), pointing to the same Amuda location for both Urakka and Urakdi, and potentially biblical Erech/Uruk.

The Epic of Gilgamesh, ancient Mesopotamian literature once considered largely mythical, may contain historical elements (Epic of Gilgamesh 2010). While scholars place Gilgamesh, king of Erech/Uruk, in southern Mesopotamia, his city might have been northern Erech/Urakka. The Sumerian King List (2010), listing Sumerian kings “when kingship descended from heaven,” mentions kingship returning to Erech multiple times, suggesting Erech’s ancient importance. Other cities in the Sumerian King List may also have been in the north, with early northern cities potentially “moved” south in memory over time.15

In summary, Tell Aqab, likely Urakka/Urakdi, near Amuda in North Syria, is the probable location of biblical Erech/Uruk.

Calneh: Washshukanni in Disguise?

Calneh is mentioned twice in the KJV Bible (Genesis 10:10; Amos 6:2), with Calno of Isaiah 10:9 likely being the same city.16a Ezekiel 27:23 mentions “Canneh”16b alongside Haran, Eden, Sheba, Asshur, and Chilmad (cities trading with Tyre). “Canneh” is likely Calneh/Calno; many scholars believe this (Jones 1856, p. 81; Smith 1948, pp. 102, 105). Spelling variations reflect Semitic language variations.

Calneh’s very existence has been questioned. In 1944, Albright argued “Calneh” should be “all of them,” denying a city named Calneh in Shinar. Genesis 10:10, according to him, should read, “And the beginning of his kingdom was Babel, and Erech, and Accad, all of them in the land of Shinar.” Many scholars followed this (Thompson 1971; van der Toorn and van der Horst 1990). Others refute Albright linguistically (Westermann 1984, p. 517; Yahuda 1946), but the idea persists (Levin 2002). Interestingly, in Amos 6:2, LXX versions read “all of you” instead of “Calneh,” seemingly mirroring Albright’s error, despite including “Calneh” in Genesis 10:10 and Isaiah 10:9. However, “thence” in Amos 6:2 (Brenton LXX) and “from there” (NETS LXX) are nonsensical without a preceding city name, an oversight by LXX translators.

Brenton LXX clearly affirms Calneh’s existence in Isaiah 10:9: “Have I not taken the country above Babylon and Chalanes, where the tower was built? (Italics added). And have I not taken Arabia,17 and Damascus, and Samaria?” (NETS is similar). “Tower” in Isaiah 10:9 likely refers to the Tower of Babel, as Genesis 10 links Calneh closely to Babel. The tower reference probably distinguishes this Calneh from similarly named cities.

KJV Isaiah 10:9 also confirms Calneh’s existence: “Is not Calno as Carchemish? Is not Hamath as Arpad? Is not Samaria as Damascus?” Gelb (1935) notes these city pairs are geographically ordered westward from Assyria. Calneh, first in line, provides a location clue.

Calneh must have been important before Isaiah and Amos, mentioned alongside other significant cities. Both prophets place Calneh first, alluding to its prior destruction as a warning of Assyrian conquest. By their time, Calneh’s destruction would have been well-known. It’s puzzling how scholars like Albright, who dismissed Calneh in Genesis 10:10, overlooked these later verses relying on the city’s name.

If Calneh was so important, it should appear in ancient history. Biblical writers have proposed locations. Some equate Calneh with Niffar (ancient Nippur) in southern Mesopotamia (Burgess 1857, pp. 374–375; Spiers 1910, pp. 374–375). Others identified Calneh (or Canneh) with ancient Ctesiphon on the Tigris (Barnes 1855, p. 222; Jones 1856), though Ctesiphon’s name history doesn’t resemble Canneh (Ctesiphon 2010). A minor city near Aleppo, northwest Syria, south of Carchemish, called Zarilab or Zirlaba, is also proposed. Spelling variations like Kulnia, Kullani, Kullanhu, Kalana, Kulunu, and Kulluna are argued to link it to Calneh (Gelb 1935; Hastings 2004, p. 185; Pinches 1893, p. 487; Pinches 1908, p. 344). Another Calneh is reported near the Khabur-Euphrates junction (Chesney 1868, p. 250; Vaux 1855, p. 11; Watson and Ainsworth 1894, p. 290). Toffteen (1907, p. 118) suggested Kalneh was Kharsag-kalama east of Nippur, citing “n” to “m” changes (Shumir=Shinar). Calneh’s location has been widely debated.

This article suggests biblical Calneh is Washshukanni (various spellings), capital of the powerful Hurrian Mitanni kingdom (Hanigalbat), rising around 1500 BC (secular timeline) (Oates 1979, p. 207). Mitanni controlled much of north Syria and Assyria (Oppenheim 1964, pp. 399–400). Washshukanni is generally placed in the Khabur triangle, but considered undiscovered. However, strong indications point to ancient Tell Fakhariya, near Ras al Ain, west of Amuda/Urakka (figs. 3 and 4). Moore (1978, pp. 183–184) dates Tell Fakhariyah back to the 7th millennium BC (secular timeline). A statue with a bilingual inscription found there links Tell Fakhariya to Sikan(i) (Greenfield and Shaffer 2001, p. 217; Huehnergard 1986; Millard 2000, p. 115). Scholars debate if Assyrian “Sikani” derives from Hurrian “Washshukanni” (Millard 2000, pp. 114–115). Astour (1992, p. 7f) outlines an itinerary placing Washshukanni near Ras al Ain and Tell Fakhariya. The Assyrian Empire map (Parpola 1987) places Sikani at the Khabur headwaters.

Returning to “Calneh” and “Canneh,” the “kanni” ending of “Washshukanni” could correspond to biblical Canneh/Calneh. Geographically, Assyrian westward marches would encounter Washshukanni/Sikan/Tell Fakhariya (Calneh) before Carchemish, aligning with Isaiah 10:9: “Is not Calno as Carchemish?” Assyrians conquered Carchemish in 717 BC (Miller 1996, pp. 173–176). Washshukanni was destroyed by Assyrians around 1250 BC (secular timeline) (McIntosh 2005, p. 93). This would place Calneh’s destruction centuries before Amos and Isaiah, making its memory unlikely to be fresh.

Timeline accuracy becomes critical. Ancient Middle Eastern history reveals constant city rises and falls. A once-powerful city could become ruins. If seeking a powerful, destroyed city predating the prophets, chronological accuracy is vital. A recurring theme is that secular Middle Eastern history is inflated by ~500 years, first proposed by Velikovsky (1952) and debated since (Courville 1971; Henry 2003).18 Subtracting ~500 years from Calneh/Washshukanni’s destruction places it in the 8th century BC, closer to Amos and Isaiah’s time (Ussher 1658), a more plausible timeframe for its destruction to be relevant to them.

Figure 4

Figure 4

Fig. 4. Tell (el) Fakhariya, near the Khabur River headwaters by the Turkish border, is proposed as Calneh. Scholars suggest this Tell could be Wassukanni, Mitanni kingdom capital, and later Assyrian Sikani. Photo: Sebastian Hageneuer (Tell el Fakhariya 2010).

We conclude Tell Fakhariya is the most likely location of Calneh, the third Babel city. Interestingly, some Jewish captives may have been settled near Calneh; Tell Fakhariya is only 2 km (1 mile) east of Tell Halaf,19 and potentially within 50 km (31 miles) of Babel itself (fig. 3).

This places Erech, Akkad, and Calneh at three points of a triangle in the Upper Khabur valley (fig. 3). Babel, the Tower and City, would logically be somewhere within this triangle, possibly equidistant from the three cities.

The Babel Tower and City: Identifying the Remains

The Tower of Babel is widely believed to have been a ziggurat, a stepped pyramid (Livingstone 2008). This is plausible, as ziggurats worldwide20 likely trace back to an original ziggurat, knowledge of which spread with human dispersal. For creationists, this original ziggurat is the Tower of Babel.

The question is, what did this original ziggurat look like? Southern Mesopotamian ziggurats, often cited as models for Babel (and sometimes claimed to be Babel), postdate Babel.21 Babel’s builders dispersed globally, carrying Tower design memories, so southern Mesopotamian ziggurats are no more likely to resemble Babel than others worldwide.

The Tower base was likely square, like subsequent levels.22 The Bible doesn’t detail Babel’s base size or planned height reaching “unto heaven” (Genesis 11:4). Scripture implies great height, requiring a large base for stability. A temple or shrine might have topped it, as seen in ziggurats like Ur’s (Oates 1979, pp. 45–47).

The number of Babel builders is unknown, with population estimates ranging from under 1,000 (Morris 1966) to 65,000 (Tower of Babel 2010). This article proposes Babel’s builders were Neanderthals, known for physical strength (Cuozzo 1998; Habermehl 2010; Trinkaus 1978), enabling harder labor than modern humans.

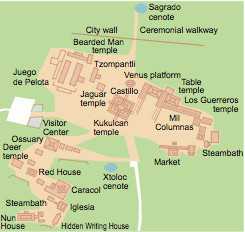

Figure 5

Figure 5

Fig. 5. The central Chichen Itza complex in Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula (Kukulcan Temple, “El Castillo,” is the Chichen Itza ziggurat). The city-ziggurat complex pattern persisted globally for millennia, supporting the Genesis Babel story. Drawing by Holger Behr (Chichen Itza 2010).

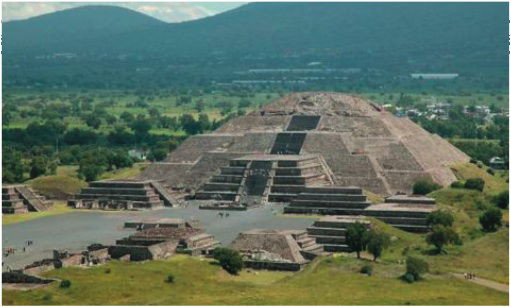

Babel included a city alongside the tower (Genesis 11: 4, 5, 8), often overlooked. 23 Ziggurats globally are rarely solitary, typically accompanied by temples, shrines, altars, palaces, and administrative buildings, walled in. Chichen Itza in Mexico (fig. 5), Babylon’s Esagila (Oates 1979, p. 148), Iran’s Chogha Zanbil ziggurat complex (Chogha Zanbil 2009), and Teotihuacan’s Pyramid of the Sun and Moon (fig. 6) (Tompkins 1976, pp. 226–240) exemplify this. Tucúme, Peru’s multi-pyramid complex (~900 years old) (Heyerdahl, Sandweiss, and Narváez 1995, p. 78), and India’s Dravidian temple compounds with gopuram towers (fig. 7) (Das 2001) also demonstrate this. These geographically diverse complexes suggest a common model originating at Babel. We should seek remnants of numerous structures alongside the Tower at Babel.

Figure 6

Figure 6

Fig. 6. The Pyramid of the Moon at Teotihuacan, Mexico, with accompanying structures. Photo by Ineuw (Pyramid of the Moon 2010).

Genesis 11:3 states the Tower was built with “burnt” (kiln-baked) brick, a durable material, potentially explaining survival.24 Bricks were bonded with “slime” (bitumen), a resource influencing Babel’s Shinar plain location. Genesis’ comment that Babel builders used burnt brick “for stone” (Genesis 11:3) likely reflects ancient Israel’s stone building tradition (Kenett 1995, pp. 18–19), contrasting with mud brick use in Israelite tells like Dan, Hazor, and Megiddo (Schaffer 2000). Solomon’s temple and palace prominently featured stone (1 Kings 5:17, 67; 7:9–12).

We should seek the oldest ruins on Earth (assuming pre-Flood structures were destroyed). Dating Babel can be confusing using non-Genesis-based methods. Secular scholars believe baked brick and bitumen for luxury structures like ziggurats appeared only ~3500-3000 BC, with unbaked brick and mud/gypsum mortar earlier (~8500 BC). This would date Babel to the later ziggurat period, creating chronological issues (explaining contemporary diverse languages and peoples) (Seely 2001; Singer 1954, pp. 250–54; Walton 1995). Genesis implies Babel predates all other ziggurats, dating Babel city and tower contemporaneously with Erech, Akkad, and Calneh as the earliest cities.

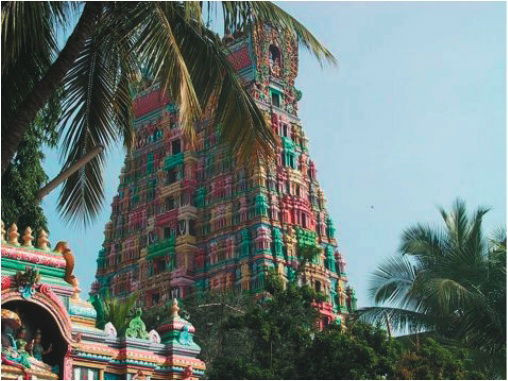

Figure 7

Figure 7

Fig. 7. South India’s ornate gopuram towers, gateways to Hindu temple complexes, display a ziggurat architectural style with Indian sculpture. This tower is part of the Srivilliputhur Andal temple complex, Srivilliputhur town, India, featured on Tamil Nadu’s government seal (Srivilliputhur Divya Desam 2011).

Khabur Triangle Babel: Plausibility and Implications

The Khabur triangle aligns with the biblical narrative. It was likely wetter in ancient times, watered by rivers from Turkish mountains and springs (Wright et al. 2007). Bitumen was readily available (Moorey 1999, pp. 332–335), with northeast Syria being an oil region (Carstens 2006). Oak trees existed for building and fuel (Deckers and Riehl 2007), or bitumen itself could have been fuel (Moorey 1999, pp. 333, 335).

The triangle’s center is ~160 km (99 miles) west-southwest of Mount Cudi, this article’s proposed Ark landing site (Habermehl 2008), a reasonable post-Flood migration distance. If the ancient shoreline was further south at the Hit-Samarra escarpment, Noah’s descendants may have avoided the coast due to Flood memories.

Moving Babel north to Syria counters the secular claim that the Tower story was inspired by Babylon’s ziggurat (Parrot 1955, p. 17). No known ziggurats exist near the Khabur triangle; the closest is Tell al Rimah (Karana), ~130 km (80 miles) east (Dalley 1984, p. 22). Those favoring a ziggurat-rich region for Babel (as Babel would inspire later ziggurats) should remember the dispersion occurred before the Tower’s completion. Babel might be found in a ziggurat-sparse area. The original Tower’s memory, however, would have spread globally, evidenced by later ziggurats worldwide.

Moving Babel north challenges the deeply entrenched belief in a southern Mesopotamian Babylon location. New ideas face resistance, and this is likely no exception.

Recognizing Babel’s Ruins Today

Thousands of years since Babel’s construction,25 ruins are expected. The Bible doesn’t detail Babel’s completion stage when building stopped, but both Tower and city were unfinished. Extra-biblical stories mention divine wind destruction (The Book of Jubilees 1913, 10:26; Josephus 1736a, Antiquities 1.4.3). While not scriptural authority, these accounts suggest significant Tower damage is possible.

Assuming a square-based ziggurat, we should seek a large square ruin area with city complex remnants nearby. Visibility above ground is uncertain. Upper Khabur plain flooding and sediment buildup over time (Deckers and Riehl 2004; Oguchi, Hori, and Oguchi 2008) may have buried Babel. Sediment depth at Babel is unknown. Tell Brak excavations may eventually provide clues, but current excavations are “substantially above the elevation of the modern plain” (Oates and McMahon 2008b). Sedimentation and ruin height make visible mounds at Babel uncertain. (We assume no Babel re-habitation, as Scripture suggests none, thus no typical tell formation from habitation layers.)

Biblical descriptions suggest baked brick and bitumen construction. Genesis doesn’t specify if these materials were used throughout or just for outer walls. Later ziggurats often used cheaper mud brick interiors (Saggs 1989, p. 57). However, Babel builders’ intent to remain in Shinar suggests a long-lasting structure, implying baked brick throughout. Mudbrick-filled ziggurats were less durable, requiring rebuilding (Saggs 1989, p. 57).

If later populations looted Babel bricks, little might remain. Babylon, for example, saw Etemenanki ziggurat bricks reused in local dwellings (Leick 2002, p. 268). However, if Babel was considered taboo or hidden by silt, looting might not have occurred.

Early post-Flood people likely possessed advanced construction technology, potentially inherited from antediluvian times (Chittick 2006). Babel could have been built with advanced skills. Secular archaeologists might misdate Babel due to its advanced technology, assuming it’s from a later, “more advanced” civilization. Their evolutionary worldview prioritizes primitive early structures and dismisses Babel as myth inspired by later ziggurats.

Archaeological excavation is crucial for further Babel area research. The Iraq War and ongoing unrest have shifted excavation focus to North Syria, previously less excavated than Iraq, especially the Khabur triangle (Akkermans and Schwartz 2003, p. 1; Crawford 2004, p. ix; McIntosh 2005, p. 43). However, excavation permits and resource limitations in Syria may pose obstacles (Matthews 2003).

Remote Sensing: Finding Babel from Above?

We have a general idea where was the Tower of Babel might be. However, finding the specific site requires a focused search.

“Terrestrial remote sensing” tools, including aerial photography and ground-penetrating methods, offer new avenues for archaeological discovery. These methods rapidly and inexpensively survey large areas, detecting subsurface features invisible on the surface, mapping them precisely, and offering interpretations based on form and context (Kvamme 2005, pp. 423–424). Parcak (2009) provides an overview of satellite remote sensing, including various satellite image types. Menze, Muhl and Sherratt (2007) discuss satellite remote sensing detection of North Mesopotamian tells as low as 6 m (19 ft). QuickBird satellite imagery has been used to locate buried archaeological remains (Masini and Lasaponara 2007), including visualizing a large buried pyramid near Cahuachi, Peru (Lorenzi 2008). High-resolution Google Earth imagery is also a useful tool, employed at Tell Brak (Jarus 2009).

Baked brick’s distinct composition from soil might make the Tower and City visible via satellite photography. Visibility is enhanced if the Tower foundation is shallow or if above-ground ruins remain. Modern remote sensing tools increase the chances of locating Babel.

Concluding Remarks

This article has presented evidence from biblical, historical, geological, and geographical sources suggesting the Tower of Babel was built in the Khabur River triangle of North Syria, within a triangle defined by Tell Brak, Tell Aqab (near Amuda), and Tell Fakhariyah, not in southern Mesopotamia near Babylon. Finding the actual Tower of Babel site requires further research and archaeological excavation. Remote sensing technologies offer promising tools for this search. The question of where was the tower of babel may yet be answered through continued investigation and archaeological exploration in this region.

References

[References list from original article – No changes needed as per instructions]

Footnotes:

1 Footnote 1: This is not an exhaustive list, but it makes the point that when dealing with the ancient Middle East, a place name can hide out under various spellings. We will have further occasion to refer to Semitic language variations of place names in this paper.

2 Footnote 2: We would therefore look for Shinar somewhere in a territory that includes two rivers.

3 Footnote 3: Zechariah 5:11 sees a vision, in which an angel tells him that a house for the ephah will be built in the land of Shinar.

4 Footnote 4: whether one believes the Ark to have landed on Mt. Cudi or Mt. Ararat

5 Footnote 5: Hammurabi therefore would have reigned about 350 years after Amraphel.

6 Footnote 6: although their language was similar to Hebrew, it would be a mistake to expect that their form of this place name would take the exact Hebrew spelling, since they did not speak Hebrew in that part of the world.

7 Footnote 7: During this ice-building time, so much water froze in very thick sheets that the ocean levels lowered drastically.

8 Footnote 8: during the catastrophic period of the Ice Age meltdown

9 Footnote 9: Akkad

10 Footnote 10: tells,

11 Footnote 11: wadi Jaghjagh

12 Footnote 12: Khabur

13 Footnote 13: at the time of the drought

14 Footnote 14: Another spelling variation of the same city appears to be Arakdi; this city is stated to be north of “Til Bari” (called Tell Barri today, located about 10 km (6 miles) north of Tell Brak), and was considered to be a fairly important place in the ninth century BC (Olmstead 1918).

15 Footnote 15: as the memory of the original ancient cities of the north dimmed.

16 Footnote 16:

a. Isaiah 10:9

b. Ezekiel 27: 23

17 Footnote 17: Arabia,

18 Footnote 18: Subtracting approximately 500 years from the final destruction of Calneh/Washshukanni puts this event in the eighth century BC, bringing it fairly close to the period of Amos and Isaiah (Ussher 1658).

19 Footnote 19: Tell Halaf;

20 Footnote 20: ziggurats that are known around the world

21 Footnote 21: date a lot later than Babel.

22 Footnote 22: square, as were all the other, receding levels.

23 Footnote 23: note that the city was mentioned first in this phrase, all three times.

24 Footnote 24: remnants of the Tower may well have survived the ages.

25 Footnote 25: thousands of years have gone by since the Tower of Babel was built,

Image Alt Texts:

- Fig. 1: Map of Mesopotamia highlighting the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, Shinar’s northern location, the Khabur triangle, and the ancient shoreline separating northern and southern regions.

- Fig. 2: Photograph showcasing the flat terrain of the Shinar plain along the Khabur River in North Syria, emphasizing the suitability of the region for settlement.

- Fig. 3: Diagram of the Khabur triangle in northeast Syria, pinpointing the proposed locations for Erech (Tell Aqab), Akkad (Tell Brak), and Calneh (Tell Fakhariya) and suggesting the Babel Tower’s potential central location.

- Fig. 4: Image of Tell Fakhariya in Syria, proposed as the location of biblical Calneh and ancient Washshukanni, illustrating the tell’s archaeological significance.

- Fig. 5: Artistic rendering of the Chichen Itza complex in Mexico, demonstrating the global pattern of city and ziggurat complexes originating from the Tower of Babel model.

- Fig. 6: Photo of the Pyramid of the Moon at Teotihuacan, Mexico, showing the pyramid and surrounding structures, reinforcing the city-ziggurat complex concept.

- Fig. 7: Image of the Srivilliputhur Andal temple gopuram in India, showcasing the ziggurat-like architectural style in Dravidian temples and their global connection to Babel’s architectural legacy.