Last Monday, a distant song reached the ears of my friend Paula Lozano and me as we explored the Sax-Zim Bog. It was the unmistakable melody of a Connecticut Warbler, a sound remarkably loud for such a small bird, especially at that distance from McDavitt Road. We considered ourselves fortunate. Our morning birding at another location had been quiet, and by the time we arrived at this spot mid-morning, most avian activity had subsided. Yet, there it was, a Connecticut Warbler’s song cutting through the stillness.

About an hour later, our path crossed with two birders from Massachusetts. They were on a mission, a desperate search for a Connecticut Warbler that had consumed their entire day. They had staked out McDavitt Road since early morning, hearing the same distant song we had. However, their quest was more than auditory; they yearned to see a Connecticut Warbler. Frustration was evident as they lamented the lack of easy public access to these elusive birds.

The question of how to spot a Connecticut Warbler is one I’ve encountered countless times over the years. The Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s All About Birds species profile aptly describes the Connecticut Warbler as “an infamously hard-to-find bird.” They are ground foragers, preferring the secluded muskeg, spruce bogs, and poplar forests. While males sing from the treetops, their foraging habits keep them hidden within the dense underbrush, making visual confirmation incredibly challenging. This elusiveness, coupled with their preference for remote habitats, has contributed to the Connecticut Warbler being one of the least studied songbirds in America.

My own early birding years in Michigan passed without a Connecticut Warbler sighting. Even if I had heard one, I wouldn’t have recognized its song. My first encounter, my “lifer,” came unexpectedly in Wisconsin during a Big Day in May 1978. The following year, another migrant appeared at Picnic Point, my beloved birding spot in Madison. It wasn’t until I moved to Peabody Street in 1981 that Connecticut Warbler sightings became more regular, often in my own backyard during spring and fall migrations. Yet, each sighting felt like a gift, a moment of pure luck.

From the 1990s onward, migrant sightings became increasingly rare for me, and years have passed without a Connecticut Warbler gracing my Peabody Street yard. By 2009, when I acquired my first decent digital camera, any Connecticut Warbler sighting felt like winning the lottery. Capturing a photograph? Even a blurry one felt like discovering the Holy Grail.

A glimpse of a Connecticut Warbler, even with its back turned, is a thrilling moment for birders.

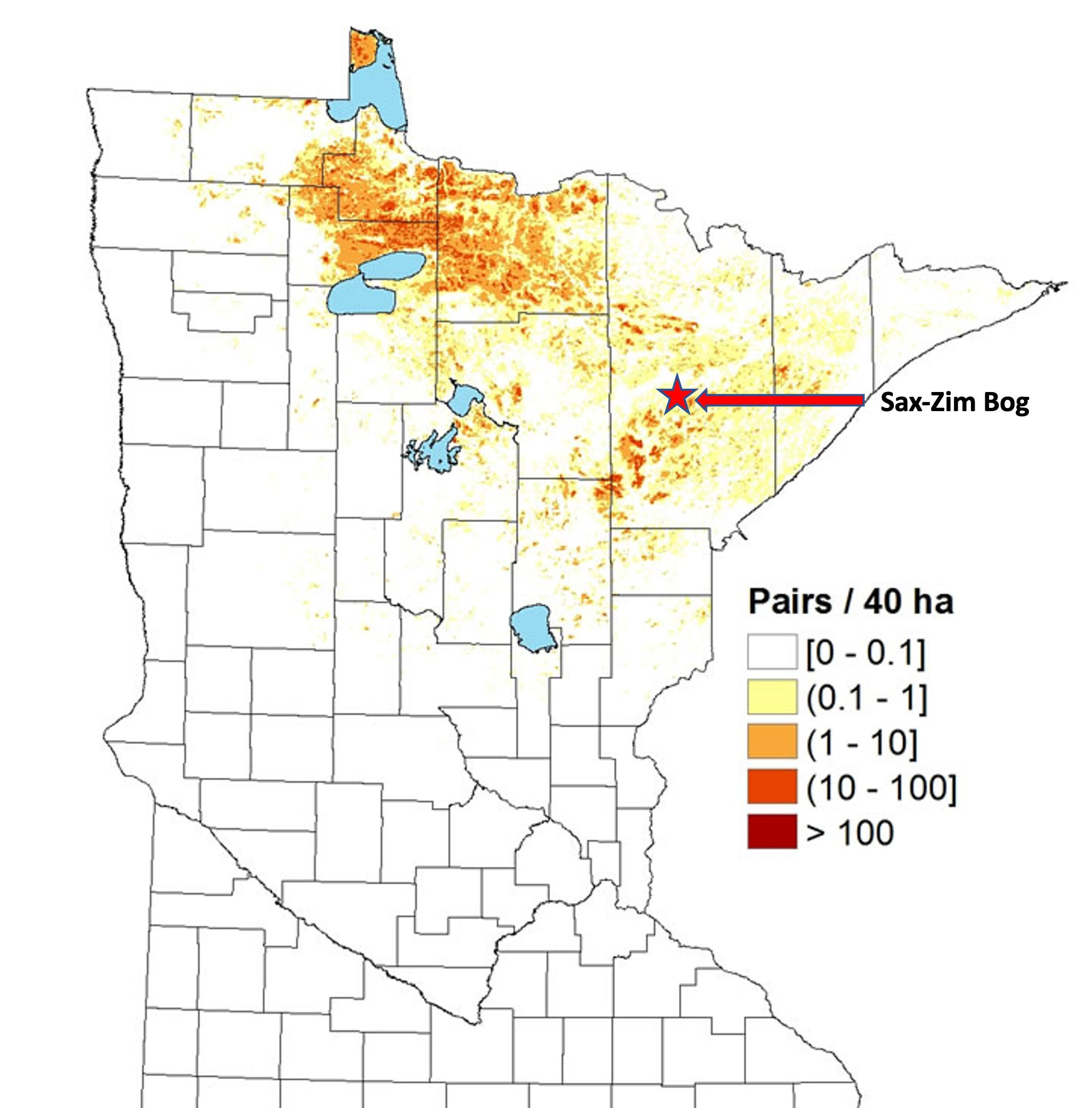

The majority of Connecticut Warbler encounters, much like my own, occur during migration. Their breeding range is confined to a narrow band of coniferous forest stretching from western Quebec to eastern British Columbia. Within the United States, they primarily breed in northern Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan.

Even within these states, their population density is low. The highest concentration exists in a small area spanning southern Ontario and northern Minnesota, with the Sax-Zim Bog just outside this core zone.

Breeding distribution map of Connecticut Warbler.

Breeding distribution map of Connecticut Warbler.

The breeding range of the Connecticut Warbler is narrowly defined, contributing to its elusive nature.

Despite not being in the densest population area, the Sax-Zim Bog’s accessibility to birders makes it a popular search location every June. When a Connecticut Warbler is located, word spreads quickly through the birding community.

Like Paula and my recent auditory encounter, most Connecticut Warblers in the Bog are “heard-only” experiences, much to the chagrin of birders desiring a closer look. However, occasionally, a bird will establish a territory near a road, path, or boardwalk. My best photographs of this species were taken in 2021, when a Connecticut Warbler sang persistently for over a week along Arkola Road.

Arkola Road in Sax-Zim Bog can sometimes offer closer views of singing Connecticut Warblers.

In 2016, I photographed another Bog nester just a short distance from Admiral Road.

Even within known habitats like Sax-Zim Bog, sightings often require patience and a bit of luck.

My only other Connecticut Warbler photographs capture a migrant at Park Point in May 2013 – the sole sighting during my Big Year.

Migrant Connecticut Warblers can appear in unexpected locations, offering fleeting opportunities for observation.

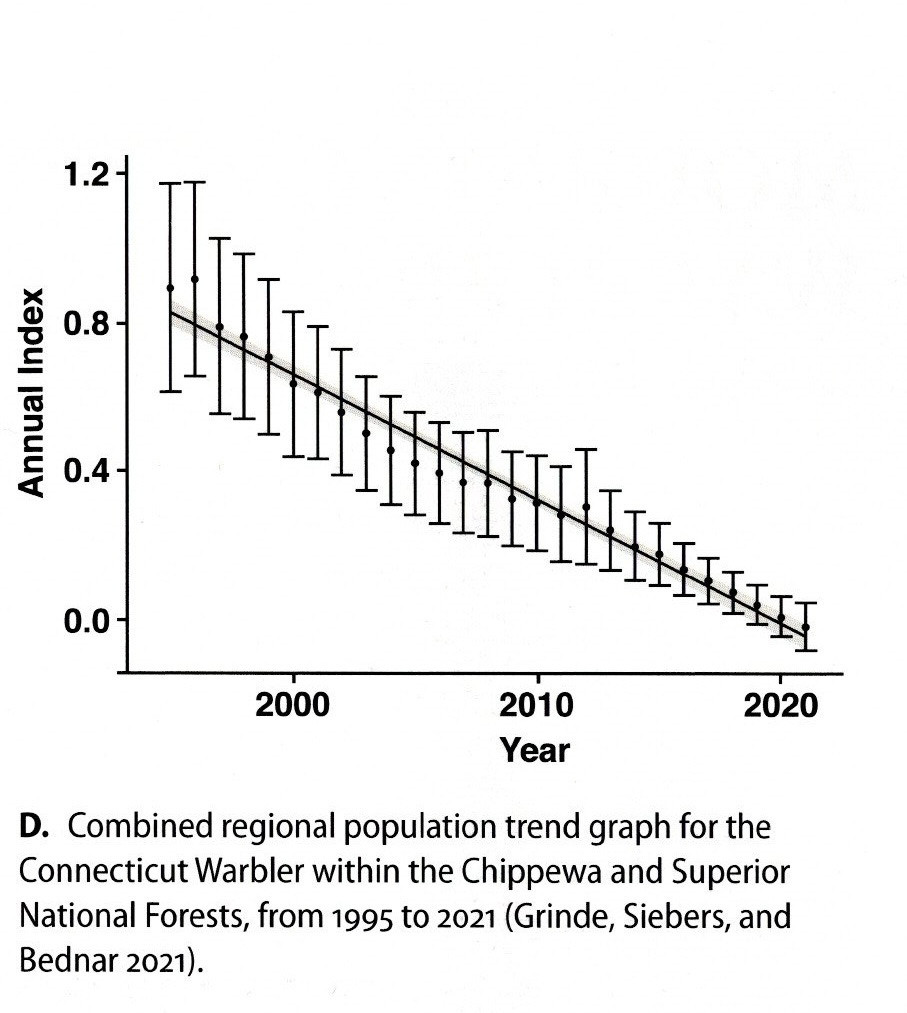

Sadly, Connecticut Warbler numbers are dwindling year after year, a decline that shows no sign of reversal. Northern Minnesota represents the southern edge of their breeding range, and the detrimental effects of warming temperatures are already evident in the Sax-Zim Bog, impacting black spruce bogs and tamarack swamps, critical habitats for these birds.

Climate change and habitat degradation are significant threats to Connecticut Warbler populations.

Minnesota’s Connecticut Warbler population within the Chippewa and Superior National Forests has experienced a significant and consistent decline between 1995 and 2021.

Population trend graph for Connecticut Warbler in Minnesota National Forests.

Population trend graph for Connecticut Warbler in Minnesota National Forests.

Data from “The Breeding Birds of Minnesota” reveals a worrying decline in Connecticut Warbler populations.

Michigan’s second Breeding Bird Atlas (2002-2008) also documented a significant reduction in records from the northern Lower Peninsula compared to their first atlas twenty years prior. They also noted fewer detections in the Upper Peninsula during the second atlas. Wisconsin’s situation is equally concerning, highlighted in a 2021 paper in The Passenger Pigeon titled “Status & Trend of the Connecticut Warbler in Wisconsin: Steep Decline Demands Urgent Conservation Action.”

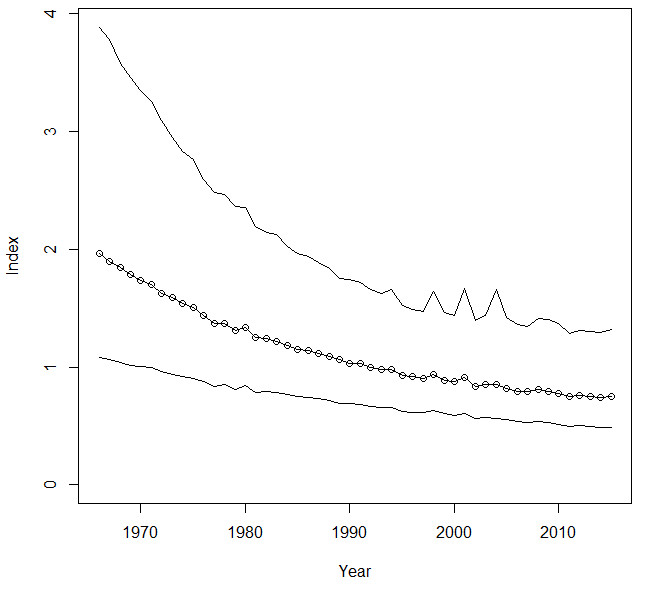

The federal Breeding Bird Survey further confirms a continent-wide significant decline in Connecticut Warbler populations.

Breeding population trend graph for Connecticut Warbler across North America, 1966-2015.

Breeding population trend graph for Connecticut Warbler across North America, 1966-2015.

The federal Breeding Bird Survey indicates a long-term decline in Connecticut Warbler breeding populations.

National Audubon has classified the Connecticut Warbler as “climate threatened,” predicting that none of its current breeding range will be climatically suitable by 2080.

During a trip to Alaska in 2022, my husband Russ and I observed the effects of climate change firsthand. Caribou were scarce, limited to areas still underlain by permafrost in Denali National Park and Preserve.

Permafrost thaw in Alaska is impacting caribou habitat and potentially benefiting moose populations.

As permafrost thaws due to rising temperatures, caribou habitat deteriorates, while areas become more favorable for moose.

Habitat shifts due to climate change may be influencing the distribution of various species.

Similarly, Connecticut Warblers might seek more suitable habitat further north as their current range becomes less hospitable, leading to a northward shift in their distribution.

Despite these declines, a substantial number of Connecticut Warblers still exist. Minnesota Breeding Bird Atlas data suggests around half a million birds breed in the state, significantly more than the entire global population of Kirtland’s Warbler. The Agassiz Lowlands of north-central Minnesota provide habitat for some of the densest populations of Connecticut Warblers on the continent, and Ontario harbors even more. This begs the question: why do birders lament the difficulty of seeing Connecticut Warblers when Kirtland’s Warblers, a far rarer species, are readily observed?

Kirtland’s Warbler habitat is accessible and conducive to observation, unlike that of the Connecticut Warbler.

Kirtland’s Warbler habitat consists of well-drained soil, making paths and logging roads easily navigable even after rain. The first Kirtland’s Warbler nest was discovered in 1903. Once scientists understood their habitat preferences, studying their nesting habits became relatively straightforward, making Kirtland’s Warbler one of the most well-studied songbirds.

Connecticut Warbler habitat in northern bogs and swamps is challenging for human access and observation.

Conversely, Connecticut Warblers nest in northern bogs and swamps, terrain extremely difficult to traverse on foot. The first Connecticut Warbler nest was found much earlier, in 1883, but their inaccessible habitat, combined with their skulking behavior, makes them frustratingly hard to spot even when their loud songs fill the air. Only one detailed study of a nesting pair has ever been published, dating back to 1961.

When Kirtland’s Warbler faced dire endangerment, managers restricted access to nesting areas, except on public roads. They recognized that birders were not only the primary beneficiaries of Kirtland’s Warbler conservation but also the most willing to contribute to their protection.

Early conservation efforts for Kirtland’s Warbler benefited from birder support and engagement.

This understanding led the US Forest Service, Michigan DNR, and Michigan Audubon to offer free guided walks to see Kirtland’s Warblers starting in the 1970s. Every guided hike I attended between 1975 and 2019 was fully booked.

Guided tours and accessible habitat make Kirtland’s Warblers relatively easy to see.

Now that Kirtland’s Warbler is no longer endangered, self-guided auto tour maps to prime roadside viewing areas are available online. Michigan Audubon and the Forest Service still offer guided tours for a small fee, departing from Hartwick Pines State Park and the Mio Ranger Station. The drive to Kirtland’s Warbler habitat from Detroit or Lansing is straightforward, and even exploring on your own along logging roads doesn’t feel remote or perilous.

The drive to the Sax-Zim Bog from Duluth is a relatively short 42 miles, but within the Bog, much of the best habitat is accessed via dirt roads, which can be challenging during wet periods. Connecticut Warblers are not concentrated or common anywhere within the Bog. Recently, the Friends of the Sax-Zim Bog has been acquiring private land in key habitat areas and constructing boardwalks to protect the delicate bog ecosystem and enhance accessibility. Last year, a Connecticut Warbler sang near the Wintergreen boardwalk for a few days, but fleetingly – I visited just before and just after its brief residency, narrowly missing the opportunity.

The core areas of Minnesota and Ontario with the highest Connecticut Warbler abundance are far more remote, lacking major highways and roads, often beyond cell phone service range. It’s no surprise that few birders venture there to add this species to their life lists.

Regardless of location, encountering a Connecticut Warbler, whether by sight or sound, boils down to the “3 P’s”: Patience, Perseverance, and Providence. Ironically, what feels like providential luck for a birder often signifies misfortune for these birds. Perhaps the most “fortunate” individual regarding Connecticut Warbler sightings was ornithologist David Wingate, who observed an astounding 75 Connecticut Warblers in one New England location in September 1987. These birds were grounded by strong winds from Hurricane Emily, a stroke of ill-fortune that concentrated them in an unusual location.

Seeing or hearing a Connecticut Warbler anywhere truly is a matter of Patience, Perseverance, and Providence.

Life is precarious for a half-ounce bird that breeds only in northern bogs and swamps, winters solely in Bolivian and southwestern Brazilian forests, and undertakes thousands of miles of migration each fall and spring. When Connecticut Warblers arrive on their breeding grounds, their priority is finding safe nesting sites, not easily accessible spots for birders. Those of us who admire this elusive warbler cherish every encounter and are grateful for the rare moments we connect with this remarkable, yet vulnerable, species.