The Himalayas, a name synonymous with towering peaks and breathtaking landscapes, are more than just a mountain range; they are a geographical and ecological marvel. When asking “Himalayas Where Is It?”, we’re not just seeking a point on a map, but delving into a region of immense biodiversity and varied climates that dictate unique ecosystems, particularly its forests. This article explores the location of the Himalayas and how this positioning shapes the incredible diversity of its forests.

Understanding the Geographical Extent of the Himalayas

The Himalayan range forms a majestic, slightly curved arc stretching from west to east, acting as a natural boundary. Geographically, the Himalayas serve as a formidable “great wall” separating the high-altitude Tibetan Plateau to the north from the fertile alluvial plains of the Indian subcontinent to the south (UPSC Notes, 2020). This vast region is conventionally divided into five distinct subregions, each with its unique characteristics:

- Kashmir Himalaya: Spanning parts of India and Pakistan.

- Himachal Pradesh Himalaya: Located within India.

- Kumaon Himalaya: Bordering India and China.

- Central Nepal Himalaya: Situated in Nepal.

- Assam Eastern Himalaya: Encompassing Assam and parts of Arunachal Pradesh in India, as well as Bhutan.

Some geographical interpretations even extend the Himalayan range to include the Hindu Kush, an 800 km long mountain range predominantly in Afghanistan (Encyclopaedia Brittanica, 2022). Understanding this extensive geographical spread is crucial to appreciating the environmental diversity within the Himalayas.

Why Location Matters: Biodiversity Hotspots in the Himalayas

The precise location of the Himalayas is not just a matter of latitude and longitude; it’s fundamental to understanding its ecological significance. The region’s unique positioning has resulted in it being recognized as one of the world’s most important biodiversity hotspots in South Asia (Reddy et al., 2017). This designation highlights the exceptional concentration of endemic species and the critical need for conservation in this area.

In fact, a significant 51% of South Asia’s biodiversity hotspots, which are predominantly forest ecosystems, are located within the Himalayan region (Reddy et al., 2017). This underscores the vital role the Himalayas play in global biodiversity conservation and emphasizes how its geographical location has fostered such rich and varied life forms.

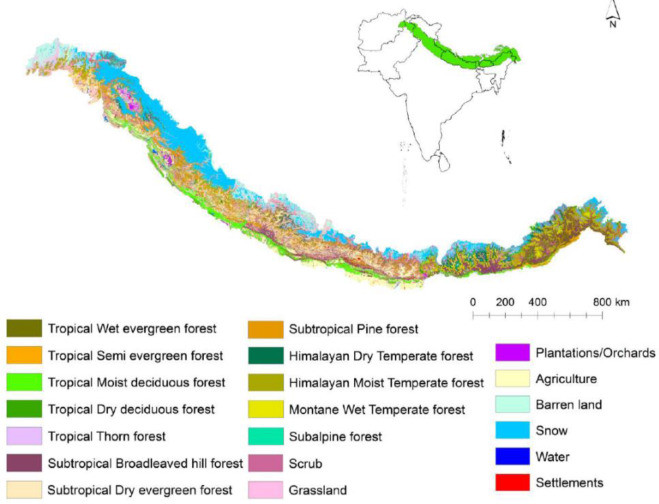

Land cover map illustrating the diverse natural forest types across the Himalayan region, a biodiversity hotspot in South Asia, highlighting the geographical distribution of various forest ecosystems.

Land cover map illustrating the diverse natural forest types across the Himalayan region, a biodiversity hotspot in South Asia, highlighting the geographical distribution of various forest ecosystems.

Figure 1.1. Land cover and natural forest types of the Himalayas. Source: Reddy et al. (2017).

Factors Influencing Himalayan Forest Types

The question of “himalayas where is it” is intrinsically linked to understanding the environmental factors that shape its forests. The type of forest that thrives in a specific Himalayan location is primarily determined by two key geographical elements: elevation and precipitation. Soil type plays a secondary, albeit still important, role in influencing vegetation growth.

For example, certain tree species, such as Mesua ferrea, also known as Ceylon ironwood, are adapted to flourish in porous soils found on steep hill slopes. Conversely, species like Quercus (oak) and Aesculus indica (Indian horse chestnut) are commonly found on lithosols, which are shallow soils developed on rock. Furthermore, key tree species that define different forest types each have their distinct geographical distribution ranges within the mountains. Pinus roxburghii (chir pine), for instance, typically grows between 800 and 1600 meters in elevation, but can reach up to 1900 meters in sheltered inner valleys (Kumar et al., 2020). Cedrus deodara (deodar cedar), endemic to the western Himalayas, is found between 1900 and 2700 meters, extending even higher in the upper Ganges River valleys. Species like Pinus wallichiana (blue pine) and Picea smithiana (morinda spruce) generally appear at higher elevations, between 2200 and 3000 meters (Singh and Singh, 1987).

Forest Types Across the Himalayan Range

The Himalayas exhibit a typical pattern of forest transition influenced by elevation. However, the east-to-west orientation of the mountain range also introduces variations in temperature and precipitation, independent of altitude, further shaping forest types. Soil types contribute to a lesser extent but are still relevant (Haq et al., 2022).

East to West Variation

Moist temperate forests are generally found at lower elevations, specifically in the lower montane regions. In the Western Himalayas, dominant species in these forests include Abies pindrow (West Himalayan fir) and Pinus wallichiana (blue pine) (Shaheen et al., 2012). As elevation increases, these forests transition into subtropical broad-leaved hill forests, characterized by species such as Olea cuspidata (wild olive) and Shorea robusta (sal), and subtropical pine forests dominated by Pinus roxburghii (chir pine) (Encyclopaedia Brittanica, 2022; Phraser, 2015). At higher altitudes, temperate forests emerge, encompassing broadleaved, mixed, and subalpine forests with species like Tsuga dumosa (Himalayan hemlock), Picea smithiana (morinda spruce), and various Abies (fir) species. The upper limit for forest growth across the entire Himalayan region averages between 3500 and 4200 meters.

Altitudinal Zonation of Forests

This general pattern of forest zonation with altitude, however, varies across the different Himalayan subregions. A comparison of forest transitions along altitudinal gradients in the Eastern and Northwestern Himalayas clearly demonstrates this. The Eastern Himalayas, stretching approximately 720 km, rise more abruptly in elevation compared to their western counterparts (Phraser, 2015). This region, encompassing parts of West Bengal, Arunachal Pradesh (India), and Bhutan, is characterized by dense broad-leaved semievergreen forests up to 900 meters, dominated by S. robusta (sal). Between 750 and 1500 meters, the vegetation shifts into what Phraser (2015) terms middle hill forests. The lower zones of these middle hill forests, ranging from 750 to 1250 meters, are dominated by Castanopsis indica, C. tribuloides, Phoebe hainesiana, and Schima wallichii. At slightly higher elevations, between 1200 and 1600 meters, various Quercus (oak) species become the dominant trees (Phraser, 2015: 97). Interestingly, dense stands of Cryptomeria japonica, a tree widely cultivated in Japan (Takahashi et al., 2021; de Jong et al., 2022), are also found in this Eastern Himalayan region between 1200 and 2400 meters.

Further up in the Eastern Himalayas, between 1500 and 2700 meters, the forests, still categorized as “warm or wet and temperate” (Phraser, 2015: 98), are largely dominated by oak and laurel species. Within this elevation band, different species prevail in narrow elevation ranges. Above 2700 meters, the forests transition into cold temperate and subalpine types, characterized by Rhododendron and various coniferous tree species. From 3600 meters upwards, the vegetation transforms into alpine scrub (Phraser, 2015). Even within the Eastern Himalayas, subregions like Bhutan and the Assam Himalaya exhibit their own unique variations in forest type transitions with increasing elevation.

In contrast, the Northwestern Himalayas, spanning an 800 km length and 200–400 km width across Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Chandigarh, and Uttarakhand, display a different pattern. In this region, rainfall, temperature (Phraser, 2015), and wind patterns all influence forest types. The Northwestern Himalayas receive between 1000 and 2000 mm of precipitation annually, with 75% falling during the monsoon season (Phraser, 2015). However, rainfall varies considerably, from as low as 600 mm to as high as 3200 mm in certain locations. Monsoon intensity decreases westward, affecting inner regions less, which in turn receive more winter snow. The geographical orientation of the mountain range also plays a role in rainfall distribution.

Based on elevation, the Northwestern Himalayas are divided into four climate zones: tropical (foothills up to 1000m), subtropical (1000–1800m), temperate (1800–3600m), and alpine (above 3600m; Mehra and Bawa, 1970). The tree line in the Northwestern Himalayas is around 3600 meters (Phraser, 2015). The tropical zone hosts tropical moist and tropical dry deciduous forests. The former thrives in areas with high rainfall and temperatures, dominated by S. robusta or mixed-species vegetation. In drier areas, tropical dry deciduous forests with diverse tree species replace the moist types (Phraser, 2015). The subtropical zone (1000-1800m) with moderate rainfall and temperatures features montane subtropical forests, blending tropical and temperate species (Phraser, 2015). These forests contain both sparse P. roxburghii stands and those dominated by Quercus incana and Rhododendron arboretum, among other species.

Further up, the temperate zone (1800-3600m) experiences reduced rainfall and lower temperatures. These monsoon montane temperate forests differ from higher-latitude temperate forests (Phraser, 2015). The lower reaches of this zone still contain Q. incana and R. arboretum, along with Cedrus and Pinus conifers. The mid-reaches are dominated by Quercus-Acer forests. Higher up, coniferous genera like Abies, Picea, Cedrus, and Taxus characterize the forests, interspersed with deciduous trees.

The Unique Case of Kashmir Valley

The general forest patterns are further modified in specific locations. The Kashmir Valley, for example, receives minimal monsoon rainfall, relying more on winter rain in January and February. This results in a distinct altitudinal forest vegetation compared to the broader Northwestern Himalayas. At the lowest elevations (1500-2100m), mixed tree species forests prevail. A coniferous forest zone exists between 2100 and 3200m, followed by a white birch forest zone from 3200 to 3600m (Phraser, 2015). In the alpine zone of the Kashmir Valley, Juniperus species and a few other hardy tree species are found, but tree growth is limited by the harsh climate.

Westernmost Extents

Further west of the Northwestern Himalayas, the typical altitudinal transition is again altered. At lower elevations, tropical rainforests transition to tropical deciduous forests dominated by S. robusta as rainfall decreases. Moving even further west, these S. robusta forests eventually give way to dry steppe forests (Encyclopaedia Brittanica, 2022), marking the westernmost ecological limits of the Himalayan forest system.

Conclusion

Understanding “himalayas where is it” is the first step in appreciating the incredible geographical and ecological complexity of this region. The location of the Himalayas, spanning across several countries and exhibiting significant altitudinal and climatic variations, is the key factor driving the remarkable diversity of its forest ecosystems. From lush tropical forests at lower elevations to hardy alpine scrub at the highest reaches, and with significant regional variations from east to west, the Himalayas stand as a testament to the power of geography in shaping biodiversity. This makes the Himalayan region not only a breathtaking landscape but also a critical area for ecological study and conservation efforts in the face of global environmental change.