I’m gazing out the window, hoping for a spark of creativity. The words just aren’t coming. Thankfully, in my line of work, nature is always a source of inspiration.

Suddenly, a thunkety-thunkety-thunk sound from behind me catches my attention. It’s Diggy, my son’s new winter white dwarf hamster. Although Diggy is usually most active at night, she often wakes up around midday for a run on her wheel.

Watching this adorable little creature, a question pops into my head. A curious naturalist never has to search far for intriguing questions. How did this little rodent become such a popular pet? Why does Diggy run on that wheel so much? What are her wild relatives like, and how are they doing in their natural habitats?

Let’s delve into the fascinating story of hamsters in the wild, explore the challenges faced by our pets’ wild cousins, and, of course, understand why hamsters are so drawn to running wheels.

A domestic golden hamster plays peekaboo

A domestic golden hamster plays peekaboo

The Quest for the Golden Hamster: Tracing Hamster Origins

There are around 18 known species of wild hamsters, and possibly more depending on different classifications. All hamster species share common traits: they are nocturnal, they gather and store food, and they live in underground burrows. Some hamster species are solitary, while others are more social. While they might all appear cute, many wild hamsters are actually quite aggressive and not suitable for domestication as pets.

The Syrian hamster, also known as the golden hamster, is the species that ignited the pet hamster craze. Ironically, this popular pet is one of the rarest hamster species in the wild. While details may vary across different historical accounts, the primary expedition to find and study these creatures is well-documented.

The Syrian hamster was encountered by explorers before, but remained largely a mystery. It was known as a golden-furred rodent. In 1930, biologist Israel Aharoni embarked on an expedition near Aleppo, an ancient city, with the goal of finding this almost mythical animal and understanding where these hamsters were from and their natural habitat.

A desert landscape in Syria, the native habitat of golden hamsters

A desert landscape in Syria, the native habitat of golden hamsters

Aharoni was a notable figure, and as Rob Dunn detailed in an engaging Smithsonian Magazine article, one of Aharoni’s key interests was identifying animals described in the Torah with their modern counterparts. He had heard tales of the “golden hamster,” whose Arabic name, “Mr. Saddlebags,” referred to their spacious cheek pouches.

By most accounts, Aharoni was not fond of travel or adventure. Anyone who has been on research expeditions knows that there’s sometimes that person who constantly complains about food and lodging, is grumpy every morning, and argues with fellow travelers. Aharoni was that person. And he was leading a challenging expedition to find a creature whose existence in the wild was uncertain. It doesn’t sound like a pleasant trip.

A close-up of a golden hamster's face

A close-up of a golden hamster's face

Despite the hardships, Aharoni persevered, driven partly by his desire to find another animal from the Torah and partly to locate a better hamster species for medical research. The Chinese hamster was being used in labs, but it didn’t breed well in captivity, necessitating constant captures from the wild.

With the help of a local hunter, the expedition finally discovered a litter of wild Syrian hamsters. This marked the beginning of a series of challenges for the newly captured hamsters. It’s quite remarkable they ever became popular pets. Shortly after being contained, the mother hamster began eating her young – a foreshadowing of a behavior that would later distress many hamster owners.

Some hamsters managed to escape. Others perished. However, enough of that initial litter survived to establish a breeding colony for research purposes. These animals bred so successfully that they became the foundation of the pet hamster industry.

Wild Syrian hamsters remain exceptionally rare and elusive in their natural origin, Syria and surrounding regions. According to Dunn, only three scientific expeditions have observed this species in the wild since Aharoni’s, with the last one in 1999.

A small Roborovski dwarf hamster in a tunnel

A small Roborovski dwarf hamster in a tunnel

Hamsters of Different Origins: Exploring Dwarf Hamster Species

Most sources indicate that today’s pet hamsters are descendants of the hamsters from Aharoni’s expedition. Because all hamsters collected on that trip originated from the same litter, pet hamsters exhibit signs of inbreeding, including predispositions to certain health conditions like heart problems.

While largely true, this isn’t the complete picture. Another expedition did manage to collect more Syrian hamsters, which were introduced into the pet trade in 1971, adding slightly to the genetic diversity.

Furthermore, several other hamster species have gained popularity as pets. My son’s hamster, Diggy, for example, is not related to the Syrian hamsters captured by Aharoni.

Diggy is a winter white dwarf hamster (Phodopus sungorus), also known by various names including Djungarian hamster and Siberian dwarf hamster. These hamsters resemble tiny cotton balls with a distinctive dark stripe down their backs. Understanding where these hamsters are from reveals a different geographic origin story.

A grey winter white dwarf hamster

A grey winter white dwarf hamster

Winter white dwarf hamsters were first identified by the renowned Russian scientist Peter Simon Pallas. Pallas’s name is well-known in natural history circles, with numerous species named in his honor, such as Pallas’s gull (and five other bird species), Pallas’s cat, and even a type of meteorite called pallasite. Interestingly, the hamster wasn’t named after him, as he initially misidentified it as a type of mouse.

In their wild origins, winter white dwarf hamsters undergo a remarkable seasonal transformation, changing their coat color from brown to white in winter. This adaptation provides camouflage against snowy backgrounds, similar to snowshoe hares. This molting process begins around September and lasts a couple of months. Domestic winter white dwarf hamsters like Diggy, however, remain white throughout the year.

These dwarf hamsters are generally more social than Syrian hamsters, which often makes them more docile and easier to handle in captivity. In our short time with Diggy, she has proven to be quite friendly. In fact, whenever I’ve felt stuck while writing this article, picking her up and letting her scamper on my arms has provided the inspiration needed to continue.

A white winter white dwarf hamster on human hands

A white winter white dwarf hamster on human hands

The Plight of European Hamsters: A Shift in Hamster Habitats

While hamsters thrive as pets worldwide, the situation for their wild counterparts is often very different. The European hamster is one of the most widespread hamster species, found across a large range in Europe and Asia. However, despite their wide distribution, their populations are facing serious challenges, highlighting that where hamsters are from isn’t always a safe haven. This species has never been popular as a pet due to its larger size and aggressive nature. In one study, captive-bred European hamsters showed aggression towards a caged ferret, attempting to attack it. Historically, they were unfortunately trapped for their fur, used to make coats. Improved regulations and changing fashion trends have thankfully helped their populations recover somewhat from fur trapping.

However, European hamsters now face an even more significant threat leading to population decline. While not yet classified as endangered, their population trend is alarming. A study published in Endangered Species Research indicates that the European hamster is “probably the fastest declining Eurasian mammal,” having vanished from 75 percent of its former habitat in Central and Western Europe.

A wild European hamster amidst foliage

A wild European hamster amidst foliage

Habitat loss was initially considered the primary culprit, but an intriguing discovery emerged. Researcher Mathilde Tissier observed that hamster populations declined particularly in areas where agricultural fields were converted to corn production. When she fed captive hamsters a diet of corn and earthworms, mimicking what wild hamsters might find in cornfields, she found a disturbing result: almost all hamsters consumed their own offspring, repeatedly. As reported in Smithsonian, this “corn-earthworm combo was not deficient in energy, protein or minerals, and the corn did not contain dangerous levels of chemical insecticide.”

Tissier’s research pointed to pellagra, a disease caused by excessive corn intake. Essentially, “Corn binds vitamin B3, or niacin, so that the body cannot absorb it during digestion.” The hamsters were suffering from nutrient deficiencies, leading to the cannibalization of their young.

While habitat loss and pesticides may still play a role in the decline of European hamsters, a significant factor is the change in their diet due to modern agricultural practices. This serves as a crucial lesson for conservationists: wildlife declines can be influenced by more complex factors than initially apparent.

Interestingly, European hamsters are thriving in urban environments. City parks in Vienna and other urban areas have become known for their hamster colonies, often becoming the best places for naturalists to observe this species. This adaptation shows how where hamsters are found can shift dramatically due to human impact on the environment.

Life on the Hamster Wheel: Connecting Pet Behavior to Wild Instincts

Just moments ago, Diggy woke up from her daytime sleep for a quick ten-minute burst of frantic sprinting on her hamster wheel. During the night, she can run for hours. What drives this behavior? And how does it relate to hamsters in their wild origins?

Exploring the reasons behind hamsters’ fascination with running wheels leads us into the realm of pet blogs, which are full of theories but often lack scientific backing. For example, many sources claim hamsters run five miles or more each night on their wheels, but concrete evidence is scarce. (I would welcome any links to published research in the comments!).

Even among scientists, various theories exist. Some suggest it’s a behavior stemming from boredom, stress, or perhaps a compulsion. After all, no hamster would do this in the wild…or would they?

Intriguingly, a fascinating research project investigated this by placing rodent wheels in outdoor settings. The study, aptly titled “Wheel Running in the Wild,” discovered that rodents (and even other species like frogs), once they learned how to use the wheel, would run on it frequently. NBC News has some great videos showing wild rodents enthusiastically using wheels.

Further research has found that rats are willing to work to gain access to a running wheel, much like they would for a food treat. The evidence suggests that rodents, including hamsters, experience the same “runner’s high” chemical response as humans.

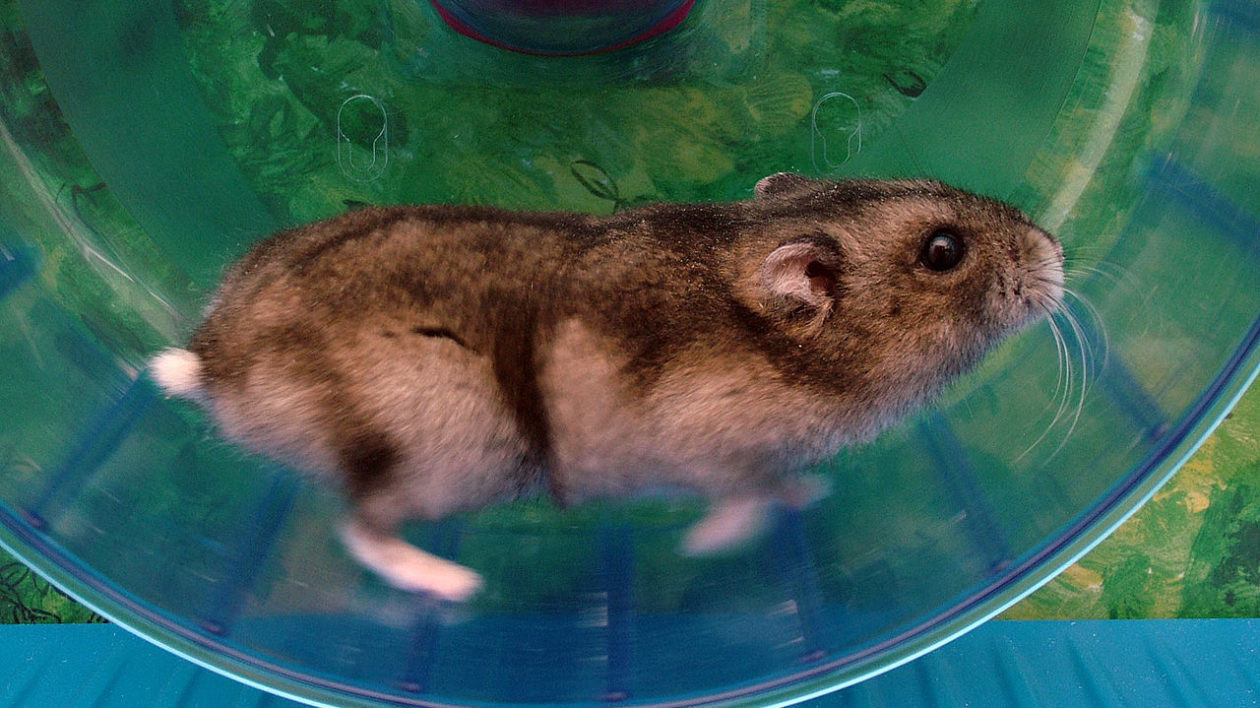

A winter white dwarf hamster on a running wheel

A winter white dwarf hamster on a running wheel

So, Diggy and I share a passion for running, and seemingly experience similar benefits. The physical advantages of exercise are clear. Research, unsurprisingly for runners, indicates that hamsters also gain significant mental benefits from running. It reduces stress and has a calming effect.

However, much remains unknown about hamsters, both on wheels and in the wild. There are still discoveries to be made even about the most common creatures around us. Perhaps a young, inquisitive pet owner will one day discover how to harness hamster power, or find a way to protect wild hamster species in their natural origins. Or maybe, we can simply appreciate seeing the world from a rodent’s perspective.