By Mika Ahuvia, Associate Professor of Jewish Studies & Comparative Religion

This article provides an overview of Jewish history and the origins of anti-Jewish prejudice. For a video version, please refer to the original source.

Understanding where Jewish people are from requires delving into ancient history, tracing their roots, and exploring the evolution of Jewish identity across millennia. This journey through time helps illuminate not only the origins of Jewish people but also the complex history of anti-Jewish prejudice, often termed antisemitism or anti-Judaism. By examining the history of Jewish people as both insiders and outsiders, particularly in ancient times, we can gain valuable insights into the persistent nature of violence and discrimination against Jewish communities. This exploration will touch upon significant events, including lesser-known instances of anti-Jewish violence such as the genocide in Alexandria (115-117 CE) and early Byzantine Christian violence (300-450 CE), to illustrate the deep-seated forces behind anti-Jewish sentiment.

Understanding the Jewish People: Basic Facts and Identity

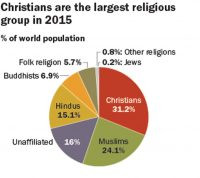

Graph showing % of world population: 31.2% Christian, 24.1% Muslim, 16% unaffiliated, 15.1% Hindu, Buddhist 6.9%, folk religion 5.7%, 0.2% Jews

Graph showing % of world population: 31.2% Christian, 24.1% Muslim, 16% unaffiliated, 15.1% Hindu, Buddhist 6.9%, folk religion 5.7%, 0.2% Jews

Global Religious Population: A bar chart depicting the absolute numbers of adherents for major world religions, emphasizing the relatively small Jewish population.

To begin understanding where Jewish people are from, it’s essential to grasp some basic facts about Jewish demographics, history, and Judaism itself. According to data from the Pew Research Center, Jewish people constitute a very small percentage of the global population, approximately 0.2%. In comparison, Christianity accounts for roughly 30%, and Islam around 24% of the world’s religious affiliation.

In numerical terms, 2015 statistics indicated approximately 14 million Jewish people worldwide, compared to 2.3 billion Christians and 1.8 billion Muslims. Within the United States, Jewish people represent a similarly small minority, accounting for roughly 1-2% of the American population, while Christians represent a majority at 71%, and religiously unaffiliated individuals at 23%.

The very term “Jewish” as a self-identifier emerged relatively late in their history, after 500 BCE. The most sacred text in Judaism, the Torah, and the Hebrew Bible predominantly use terms like “B’nei Yisrael” or “B’not Yisrael,” meaning “the sons or daughters of Israel,” alongside “Israelites” and “Hebrews.”

Defining “Jewish” and tracing the origins of the Jewish people is complex. As scholar Steven Weitzman explores in his book, “The Origins of the Jews: The Quest for Roots in a Rootless Age,” the question is multifaceted and politically charged.

Book Cover: “The Origins of the Jews: The Quest for Roots in a Rootless Age” by Steven Weitzman, highlighting the complexity of Jewish origins.

However, geographically, the origins of the Jewish people are firmly rooted in the ancient Middle East, a region that served as a crucial crossroads for powerful ancient empires, including the Egyptian, Babylonian, and Assyrian empires.

Ancient Israelites: Forging a Shared Identity in the Levant

The narrative of where Jewish people are from begins with the ancient Israelites, who emerged in the Levant, also known as ancient Canaan or modern Israel, before 1000 BCE. These ancient people were bound together by a shared sense of ancestry, mythology, rituals, and historical experiences.

Central to their identity was the belief in their descent from the patriarchs: Abraham, his son Isaac, and his grandson Jacob. Jacob himself was renamed “Israel” in the Bible, a significant event suggesting a collective memory of a name transformation integral to their history.

Illustration showing Moses and the parting of the Red Sea

Illustration showing Moses and the parting of the Red Sea

The Exodus narrative, recounted in the second book of the Hebrew Bible, served as a powerful unifying myth. This story of liberation from enslavement in ancient Egypt became a cornerstone of Israelite identity.

The Exodus story recounts a period of drought in Canaan that compelled the Israelites to seek sustenance in Egypt. Initially a minority, they eventually faced enslavement until divine intervention, orchestrated by God through miraculous plagues and the prophet Moses, led to their freedom.

Following their liberation, Moses led the Israelites through the wilderness between Egypt and Canaan. At Mount Sinai, they received divine instruction and laws. Ultimately, they returned to the “Promised Land” of Canaan, the land where Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob had resided centuries before.

Whether the Exodus is understood as a literal historical event or a mythic narrative, its impact on the ancient Israelites is undeniable. Around 1000 BCE, the Israelites deeply identified with this liberation story, much like Americans connect with the narrative of the American Revolution, even without direct lineage to participants. The Exodus narrative became a potent force, forging a collective identity and shared history for the Israelites.

The Torah: Divine Instruction and Distinctive Practices

A crucial element of the Israelite shared story is the revelation of the Torah, a sacred text whose name in Hebrew translates to “instruction” or “teaching.” The Greek translation, “nomos” or “law,” is reflected in Christian Bibles where “the law” often refers to the Hebrew Torah.

Today, “Torah” specifically denotes the first five books of the Hebrew Bible: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. These texts contain a wide range of laws, narratives, and teachings considered foundational to Judaism.

Torah scroll unfurled, showing dense Hebrew writing and a metal yod (pointer)

Torah scroll unfurled, showing dense Hebrew writing and a metal yod (pointer)

Many laws within the Torah, such as prohibitions against murder and theft, are universal principles essential for societal order, found in various legal codes of the time.

However, certain practices within Hebrew law particularly distinguished the ancient Israelites. These included male infant circumcision on the eighth day after birth, the observance of the Sabbath as a day of rest, and dietary laws known as kashrut or kosher laws, notably the prohibitions against eating pork and mixing meat and dairy. These distinctive practices played a significant role in shaping early Jewish identity and differentiating them from surrounding cultures.

The “Golden Age” and the Division of Ancient Israel

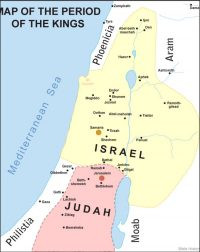

Kingdom of Israel and Judah Map

Kingdom of Israel and Judah Map

The period from 1010 to 931 BCE, during the reigns of King David and King Solomon, is often considered the “Golden Age” of ancient Israel. King David is credited with establishing Jerusalem as the central city, while King Solomon is associated with the construction of the First Temple in Jerusalem around 957 BCE.

Ancient Israelite society was traditionally structured around twelve tribes, with ten in the northern part of the region and two in the south.

In 722 BCE, the Assyrian Empire conquered the ten northern tribes of Israel. Only the southern tribes, residing in the smaller Kingdom of Judea, maintained a degree of self-rule. Thus, the “Golden Age” was relatively brief, spanning only a few generations. For much of their history, the ancient Israelites were a smaller group navigating the complex political landscape dominated by larger, more powerful empires, striving to preserve their identity and faith in a polytheistic world.

Babylonian Conquest and the First Diaspora

In the 6th century BCE, the Kingdom of Judea faced another major turning point with the Babylonian conquest. This event had the potential to extinguish Jewish history entirely. Babylonian conquest practices involved not only destruction and plunder but also the exile of elites, the very individuals who sustained cultural and societal continuity.

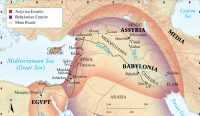

Map of Assyrian and Babylonian Empires

Map of Assyrian and Babylonian Empires

In 586 and 587 BCE, a significant portion of the Judean population, primarily elites, were exiled to Babylonia. Simultaneously, some Judeans fled to Egypt. This period marks the beginning of the Jewish diaspora, derived from the Greek word for “dispersion,” signifying the scattering of Jewish people across the Middle East and eventually the world.

However, the Babylonian conquest did not signify the end of Jewish history. A key factor in their resilience was the Israelite belief that God worked through historical events, even tragedies. The prophet Jeremiah, a pivotal figure, critiqued his fellow Israelites for insufficient faith and idolatry. Yet, he also prophesied that despite the Babylonian exile being a form of divine punishment, God would eventually restore them to Judea after 70 years (Jeremiah 29:10).

From this perspective, the destruction of the Temple and exile were not seen as victories of Babylonian gods but as divine lessons orchestrated through the Babylonians. This theological interpretation provided a framework for survival and hope amidst catastrophe.

Return to Judea under the Persian Empire

The Babylonian Empire’s dominance was short-lived. Around 70 years after conquering Judea, as Jeremiah had foretold, the Persian Empire, under Cyrus the Great, conquered Babylon in 539 BCE.

The Persians implemented a vastly different policy towards conquered peoples. Instead of suppression, they aimed for stability by allowing exiled populations to return to their homelands and live according to their ancestral customs. They even provided resources to rebuild temples.

Map of Persian Empire

Map of Persian Empire

Persian Emperor Cyrus, uniquely referred to as “Messiah” or “anointed one” in the Hebrew Bible (Isaiah 45:1), permitted the Israelites to return to Judea. From this point onward, they became known as Judeans (eventually evolving into “Jews”). They often continued to refer to themselves as Bnei Yisrael, descendants of Israel.

While acknowledging Persian rule, these Judeans maintained their ancestral laws and traditions. Around 515 BCE, the Torah was codified into a written sacred text, transitioning from primarily oral tradition to a written form.

By approximately 500 BCE, what unified the Jewish people was a shared allegiance to one God, a common lineage tracing back to legendary ancestors, the foundational Exodus myth, distinctive rituals like Sabbath observance, and a belief in divine action within history, all encapsulated within the Torah.

Hellenistic Influence and the Expanding Diaspora

![]() Alexander Mosaic Detail

Alexander Mosaic Detail

The next major empire to impact Jewish history was that of Alexander the Great. Beginning in 334 BCE, Alexander’s conquests rapidly expanded Hellenistic (Greek) influence across the Middle East. This era accelerated Jewish migration and settlement outside of Judea.

Jewish people served in Alexander’s armies, traveling and settling in newly conquered territories. Alexander established numerous cities named Alexandria throughout the Middle East and Mediterranean (marked “A” on the map). The most prominent was Alexandria in Egypt.

Many Jewish mercenaries relocated to Alexandria, Egypt, which also became a major center of Hellenistic culture and learning, housing the renowned Library of Alexandria.

Alexander granted land to his soldiers in these new Alexandrias, encouraging settlement after military service. By the first century CE, centuries later, the Jewish community in Alexandria, Egypt, was deeply integrated into the Hellenistic world.

First Century Jewish Identity: A Global Presence

Philo of Alexandria, a prominent Jewish philosopher of the first century CE, described the Jewish population of his time as widespread:

“For so populous are the Jews that no one country can contain them, and therefore they dwell in many of the most prosperous countries in Europe and Asia, both in the islands and on the mainland.

And while they hold the holy city where stands the sacred temple of the Most High God to be their mother city [meaning Jerusalem], yet those which are theirs by inheritance from their fathers, grandfathers and ancestors even farther back, are in each case accounted by them to be their fatherland, in which they were born and reared, while to some of them, they have come at the very time of their foundation as colonists as a favor to the founders.”

-Philo of Alexandria, Flaccus 46

Scholar Cynthia Baker, in her analysis of this text, highlights Philo’s depiction of a hybrid Jewish identity. Jerusalem remained the central “mother city,” but Jewish people considered their places of birth and ancestry as “fatherlands.” Centuries of migration and integration within the Hellenistic world had created a global Jewish presence.

By the first century CE, Jewish identity was becoming multifaceted, encompassing both Jewish and Alexandrian, Jewish and Roman, Jewish and Asian, Jewish and Syrian, Jewish and Macedonian identities.

The New Testament, in the Acts of the Apostles, further illustrates this dispersion, stating that in Jerusalem, “there were staying Jews, pious men, from every nation.” (Acts 2:5). This recognition of Jews “from every nation” underscores the widespread diaspora and the evolving nature of Jewish identity.

Thus, by ancient times, Jewish people, originating from the Israelites of Canaan, had spread across the Mediterranean and into Asia. They were united by monotheism, shared ancestry, history, and distinctive practices, all documented in the Torah and Hebrew Bible.

Judaism: Ethnicity, Religion, and Culture

Book Cover: “How Judaism Became a Religion” by Leora Batnitzky, exploring the complex definition of Judaism.

Defining Judaism is complex. It encompasses elements of ethnicity, religion, and culture. Leora Batnitzky’s book, “How Judaism Became a Religion,” delves into this intricate question.

Surveys of Jewish individuals in America reveal diverse self-identifications, with some identifying religiously, others culturally or ethnically, and some with no religious affiliation. The Pew Research Center offers an interactive online calculator to explore these statistics.

In essence, Judaism is a multifaceted phenomenon, simultaneously an ethnicity, a religion, and a culture, yet transcending any single category.

Core Beliefs of Judaism: Summarized by Ancient Sages

How can Judaism be succinctly summarized? Ancient Jewish sages provided insightful condensations.

Rabbi Hillel, a sage from the first century CE, when challenged to summarize the entire Torah while standing on one foot, famously stated: “[W]hat is hateful to you, do not do to your neighbor. That is the entire Torah. The rest is commentary. Go study.” (Shabbat 31a). This “Golden Rule” captures a central ethical principle in Judaism.

Around the same time, Jesus, a Jewish teacher who later became central to Christianity, was also asked to summarize the most important commandment. He offered two: First, quoting Deuteronomy 6:4, he said, “Hear, O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is one,” referencing the foundational Sh’ma prayer in Judaism.

Beginning of the Shema prayer in Hebrew: “Shema Israel, Adonai eloheinu, Adonai echad.” “Hear, oh Israel, God is our God, God is one.” Via NCSY Education, Shema Translated and Explained.

Second, he stated, “You shall love your neighbor as yourself,” adding, “There is no other commandment greater than these.” (Mark 12:29-31).

Both Hillel and Jesus, drawing from Jewish tradition, emphasized similar ethical principles of reciprocity and neighborly love as core tenets of Judaism. This highlights the significant shared ground between early Judaism and early Christianity.

The Shifting Meaning of “Jew” Over Time

Book cover:

Book cover:

The meaning of “Jew,” particularly in the eyes of non-Jews, has been fluid and often contradictory throughout history. Cynthia Baker’s book, “Jew,” explores these shifting perceptions.

Historically, “Jew” has been associated with opposing traits: materialism and intellectualism, socialism and capitalism, cosmopolitanism and parochialism, chosenness and cursedness.

This contradictory perception extends beyond Western contexts. Zhou Xun, in “Chinese Perceptions of the ‘Jews’ and Judaism,” notes that in China, “…anything which is not Chinese is Jewish, at the same time anything which is Chinese is also Jewish; anything which the Chinese aspire to is Jewish, at the same time anything which the Chinese despise is Jewish.” (p.16).

Even in regions with limited Jewish populations, “Jew” has become a symbolic term embodying diverse and often conflicting ideas.

Ancient Perceptions of Jews: Suspicion and Prejudice

Ancient Greeks and Romans often viewed Jewish monotheism with suspicion and strangeness, finding it peculiar that Jews rejected other gods.

They also criticized and mocked Jewish customs. The Sabbath was seen as laziness, circumcision as barbaric, and dietary laws as absurd and antisocial. These criticisms fueled prejudice.

Despite this, Jewish communities flourished in the Hellenistic and Roman periods. As mentioned, Jewish soldiers served in Alexander’s armies and established communities in places like Alexandria, Egypt.

Archeological evidence from Egypt provides some of the oldest physical traces of Jewish presence outside of Judea. Synagogues were built, and the Torah was translated into Greek in Egypt around the 3rd century BCE, a translation recounted by the Jewish historian Josephus (Antiquities of the Jews — Book 12, Chapter 2). This Greek translation, known as the Septuagint, later became the basis for the Christian Old Testament.

Illuminated manuscript showing Josephus with a white beard wearing a robe

Illuminated manuscript showing Josephus with a white beard wearing a robe

However, tensions arose in first-century BCE Egypt between the Greek elite and the Jewish community. Greek immigrants began to circulate negative retellings of the Exodus story, portraying Jews as undesirable, diseased, and expelled from Egypt due to plague.

While native Egyptians may have harbored resentment towards both Greek and Jewish immigrants, it was within the Greek population of Egypt that the earliest anti-Jewish writings emerged, accusing Jews of separatism and unsociability.

Roman Rule and Escalating Anti-Jewish Sentiment in Alexandria

Roman conquest of Egypt in 30 BCE worsened inter-communal relations. Roman administration initially aimed to strip Greek immigrants of their privileged status, including access to education, political participation, athletic events, and tax exemptions. Greeks protested vehemently.

A Roman compromise allowed Greeks and some Alexandrian Jews to retain certain privileges, but those in rural areas were reclassified as foreigners, losing special rights. Alexandrian Greeks reacted by arguing that all Jews should be considered foreigners. Anti-Jewish rhetoric intensified significantly during this period.

Greeks accused Jews of being antisocial, lawless or having bizarre laws, misanthropic, and even cannibalistic, alleging secret human sacrifices. The core resentment stemmed from the perceived unfairness of Romans granting privileges to Jews while diminishing Greek status.

The provided text snippet about weapon categories seems unrelated and likely inserted in error. It should be disregarded in the context of this article.

David Nirenberg, in “Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition,” argues that exclusion was central to ancient Greek identity. Loss of privilege was perceived as an attack on their identity. While Roman imperialism was the true source of diminished Greek status, Greeks focused their anger on the Jewish community, who had previously shared similar privileges.

Blaming Jews also served to unite the Greek population with potentially resentful native Egyptians against a common “outsider” group.

Genocide in Alexandria and the Destruction of Egyptian Jewry

The first century CE witnessed increasing anti-Jewish violence in Alexandria. Riots and mob attacks against the Jewish quarter became frequent. In 66 CE, Josephus reported a massacre of 50,000 Jews by Greeks in Alexandria. However, in 115 CE, violence reached a genocidal scale.

Historical accounts of the 115 CE events are primarily from the victors’ perspective, often blaming Jews for rebellion. However, it is plausible that the Jewish community was attacked without provocation.

Evidence suggests the near annihilation of the Jewish population of Egypt, both in Alexandria and the countryside. Roman tax records show confiscation of Jewish property. For at least a century afterward, Egyptians celebrated a “day of victory” commemorating the destruction of the Jewish community.

Anti-Jewish rhetoric proved devastatingly effective. Even after the elimination of Egyptian Jewry, anti-Jewish suspicion persisted in Greek and Roman writings. This anti-Judaism had political, economic, cultural, and religious dimensions.

Christian Divergence and Early Christian Anti-Judaism

Jesus was Jewish, his scriptures were Jewish, and his first followers were Jewish. However, his execution by Roman authorities, with the cooperation of Jerusalem’s Jewish priests, became a point of divergence.

From a Jewish perspective, a messiah was not expected to die. Jesus’ death posed a theological challenge for many Jews, contributing to the fact that many did not accept him as the Messiah. The movement that grew around Jesus gained traction primarily among non-Jews, former pagans.

Christian leaders sought to differentiate their movement from its Jewish roots. Christianity was presented as a fulfillment, or even a replacement, of Judaism. Christians claimed to be the “true Israel” and appropriated the term “Israel” for themselves (Romans 9).

They argued that Jews misinterpreted their own scriptures, reading them too literally, thus failing to recognize Jesus as the messiah. Later Christian theology asserted that Jewish disbelief was divinely ordained, intended to allow time for Gentiles to convert to Christianity before the Second Coming of Christ (Romans 11).

The Roman destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE was interpreted by Christians as divine validation of Christian claims and a sign of Jewish rejection by God, although Jewish interpretations differed significantly.

Consolidation of Catholic Power and Byzantine Anti-Jewish Laws

Book Cover: “When Christians Were Jews: The First Generation” by Paula Fredriksen, highlighting the early period of overlap and divergence between Christianity and Judaism.

In the second century CE, diverse Christian groups competed for theological dominance. Paula Fredriksen, in “When Christians Were Jews: The First Generation,” notes that these groups frequently accused each other of being “too Jewish,” using “Jewish” as a derogatory label for theological error.

After 313 CE, when Emperor Constantine legalized Christianity, the Catholic Church gained imperial support. Ironically, this led to increased persecution, initially directed at other Christian groups deemed heretical.

Book cover:

Book cover:

Ross Shepard Kraemer, in “The Mediterranean Diaspora in Late Antiquity: What Christianity Cost the Jews,” details how the Catholic Church, backed by imperial power, targeted Christian nonconformists like Manichaeans, Montanists, and others, suppressing their movements.

Following the suppression of other Christian groups, the Church turned against traditional Roman paganism. From 391-2 CE, the Byzantine Empire outlawed traditional Roman religion, punishable by death or exile.

After 418 CE, the focus shifted to Jews. Byzantine law codes, such as the Law Code of Theodosius and Justinian, implemented discriminatory laws against Jews. These laws prohibited intermarriage between Jews and non-Jews, barred Jews from civil service, the military, and judicial roles. Construction of new synagogues and renovation of existing ones was forbidden, as was conversion to Judaism.

In 429 CE, the Byzantine Emperor abolished the official Jewish leadership structure, the “patriarchate,” which had emerged after the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE.

Despite their shared origins, Christianity increasingly targeted Judaism. The Catholic Church developed a theological framework that allowed for Jewish existence, but in a subjugated state, meant to testify to Christian “truth” and await eventual conversion at Christ’s Second Coming. Many Christians hoped for mass Jewish conversion at the Second Coming, with dire consequences for those who refused.

Fifth-Century Anti-Jewish Violence

Ross Shepard Kraemer’s “What Christianity Cost the Jews,” provides examples of fifth-century anti-Jewish violence.

Attacks on Jewish communities frequently occurred during Easter Holy Week, commemorating Jesus’ crucifixion. In 423 CE, a Byzantine law proposed to prohibit the indiscriminate seizure or burning of synagogues, indicating that such actions were already taking place.

The proposed law also stipulated compensation for Jews for seized or burned synagogues. However, surviving Christian letters reveal that these laws were never enforced. Influential Christian figures like Ambrose and Simeon argued that providing restitution to Jews was an affront to the Catholic Church’s dignity.

Thus, even when secular authorities attempted to offer Jews legal protection, Christian leaders undermined these efforts, preventing justice and perpetuating a climate of impunity for anti-Jewish violence.

Medieval Anti-Judaism and Expulsions

Anti-Judaism continued throughout the medieval period in Europe. Between 1100 and 1800, Jewish communities were expelled from European cities thousands of times, as visualized on the map below. Larger circles on the map represent multiple expulsions.

Map of Medieval Jewish Expulsions

Map of Medieval Jewish Expulsions

Economists have linked these expulsions to periods of economic hardship, including poor weather, corruption, or plagues. Jewish communities often served as scapegoats during crises, with expulsions presented as a form of decisive action by leaders.

In 1391, in Spain, during Easter Holy Week, Christians attacked Jewish communities, though without official Church authorization. Attackers offered Jews the choice of conversion to Christianity or death.

Numerous Jews were killed, many fled, and many converted. This marked the disappearance of Jewish populations from certain areas of Spain for the first time in millennia. However, as David Nirenberg argues in “Anti-Judaism: A Western Tradition,” this did not end anti-Jewish prejudice.

Following mass conversions, conversos (those converted from Judaism) were often suspected of insincere conversion. In the 14th and 15th centuries, the discourse around “Jews” began to shift from religion to ethnicity or race, a fixed and unchangeable category, as discussed in this conversation with historian Ana Gómez-Bravo.

Even the physical absence of Jewish communities in parts of Spain did not eradicate anti-Jewish prejudice. The underlying system of anti-Jewish ideas proved remarkably resilient.

Understanding Anti-Jewish Prejudice Across History

Studying anti-Judaism historically and in the present requires critical inquiry. When encountering anti-Jewish ideas or violence, it is crucial to ask: Who holds power? What is the social standing of Jews? Who are the attackers, and who benefits? How is prejudice translated into policy?

Historically, anti-Jewish attacks are not primarily about Jews themselves or their religious distinctiveness. They are fundamentally about the precarious social status of Jewish people as “outsiders” and their utility as scapegoats during crises.

By targeting, dehumanizing, and attacking Jews, perpetrators gain political, economic, and social advantages, especially in societies with deep inequalities.

Analyzing anti-Jewish prejudice throughout history necessitates examining the perpetrators, beneficiaries, and the broader societal context, recognizing that Jewish people have often served as vulnerable targets for political and social manipulation.

Further Exploration of Anti-Jewish Prejudice and Jewish History

Podcast Series Link: A collage image linking to a podcast series on Judaism, Jewish history, and antisemitism, offering further learning resources.

To delve deeper into Judaism, Jewish history, and anti-Jewish prejudice, explore our podcast series featuring professors at the University of Washington. These 30-minute episodes offer accessible insights into these complex topics. [Link to podcast series]