Latin, often dubbed a “dead language,” echoes through history, yet its origins are vibrant and deeply rooted in the ancient world. While modern learners appreciate its structured elegance, early Latin was a far cry from the polished language of Virgil and Cicero. This is the narrative of Latin’s formative years, exploring its beginnings and evolution over its first five centuries.

Latium and the Rise of Rome

To answer the fundamental question, Where Did Latin Come From?, we must journey back approximately 2,700 years. The genesis of Latin can be pinpointed to around 700 BC, in the nascent settlements scattered across the Palatine Hill. The people who spoke this emerging language were the Romans, named after their legendary founder, Romulus.

In this era, Rome was not the imposing empire it would become. The Romans were, in fact, a relatively insignificant people group, numbering only a few thousand. Their lives were simple, residing in modest dwellings, speaking their own unique language, practicing their distinct religious beliefs, and adhering to their own customs – a pattern mirrored by numerous other communities across ancient Italy.

Map depicting Italy and the region of Latium, highlighting the area where Latin originated.

Map depicting Italy and the region of Latium, highlighting the area where Latin originated.

This land was not yet known as Italy, but as Latium. Latium was a region of diversity, not a unified nation. It was a mosaic of various groups, related yet distinct, each with their own ethnicity, religious practices, social structures, and, crucially, languages. In contrast to today’s linguistic landscape where major languages like English or German are spoken by millions, languages in ancient Latium were often confined to communities of just a few thousand. Interestingly, the ancient world boasted a greater linguistic diversity than we see today, and history has witnessed the extinction of more languages than are currently spoken.

READ MORE: When Did Latin Die?

Within the Latium region, the Romans were just one group among many, and not particularly prominent ones. The Etruscans, located to the north in modern Tuscany, were considerably more powerful and numerous. Unlike the Romans, who were initially confined to a single settlement, the Etruscans controlled numerous city-states. It would have been unimaginable at the time that within a few centuries, the language of these seemingly unremarkable Romans would become the lingua franca of the entire region.

Archaic Latin: The Language of Early Rome

The creation of a distinct language often requires isolation and independent development within a community. This is precisely what transpired over two millennia ago in Latium. Legend attributes the founding of Rome in 753 BC to the twin brothers Romulus and Remus, with some accounts claiming they were offspring of Mars, the god of war.

Their relationship, however, was far from divine harmony. Shortly after embarking on founding a city together, Remus ridiculed the walls Romulus had erected on Palatine Hill. In a fit of rage, Romulus murdered his brother.

Remus, Romulus, and the She-Wolf. By Rosemania – https://www.flickr.com/photos/rosemania/5384048970, CC BY 2.0.

While much of this narrative is likely mythical, most historians concur with the mid-8th century BC dating for Rome’s foundation. Latin first emerged on Palatine Hill, as the unique language of a small community. Remarkably, the very site of this early settlement is believed to be the location of the Forum Romanum (Roman Forum), which would become the central hub of Rome and its vast empire throughout antiquity, and remains a significant historical site today.

Approximate boundaries of language groups on the Italian peninsula during the 6th century BC. By Iron_Age_Italy.png: User:Dbachmannderivative work: Ewan ar born – Iron_Age_Italy.png, CC BY-SA 3.0.

The language spoken by Rome’s founders would have been related to the tongues of their neighbors, from which it evolved. The precise linguistic ancestry of pre-Latin Rome remains uncertain, but early Latin shared close similarities with Oscan and Umbrian dialects.

Comparative analysis of ancient texts from these three languages reveals a shared vocabulary and grammatical structure. However, the languages were not mutually intelligible. The relationship can be likened to that between Italian and Spanish – related but distinct. Linguists categorize Latin, Oscan, and Umbrian within the Italic language family, reflecting their shared origins.

The exact nature of their relationship—whether they are sibling languages from a common ancestor or if one is ancestral to the others—remains a subject of ongoing linguistic research.

The Advent of Written Latin

Typically, societies develop spoken language before written forms. Languages generally begin as oral traditions, and writing systems evolve over time. The introduction of writing marks a pivotal moment in a language’s history.

The question arises: How long did early Romans speak Latin before committing it to writing? Archaeological evidence suggests the transition to written Latin was relatively swift.

Archaeological discoveries within the Forum Romanum include a stone inscription dating back to the 6th century BC. Although largely illegible, it clearly demonstrates the use of Latin letters during this period, representing the earliest known instance of written Latin. Additionally, the “Praeneste Fibula,” a golden cloak pin from the same era, bears the inscription, “Manios me fhefhaked Numasioi.”

The Praeneste Fibula – note that the inscription reads from right to left. By Pax:Vobiscum – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0.

At this stage, Latin lacked standardized spelling and grammar. The inscription reflects a phonetic approach to writing, capturing the spoken sounds of the language. A fixed system of correct spelling was yet to emerge. This would change as the language developed.

In Classical Latin, the inscription would be rendered as, “Manius me fecit Numerio,” translating to “Manius made me for Numerius.” This suggests Manius was a goldsmith who signed his creations. These artifacts confirm that written Latin appeared soon after Rome’s founding. Written Latin is at least two and a half millennia old, and potentially even older.

How did the Romans adopt writing so rapidly? They benefited from external influence. Instead of developing their own alphabet from scratch, they adopted and adapted the Etruscan alphabet.

Etruscan Influence and the Latin Alphabet

The Etruscans, Rome’s more advanced neighbors to the north, spoke a language unrelated to the Indo-European family to which Italic languages belonged. In fact, Etruscan remains linguistically isolated, with no known relatives, living or extinct!

The Romans, primarily an agrarian society, stood to gain significantly from the more sophisticated Etruscan civilization. Early interactions fostered close relationships and trade between the two peoples. Beyond the alphabet, the Romans also adopted Etruscan vocabulary, incorporating words like persona (person) and fenestra (window).

These loanwords hint at other cultural and technological exchanges. Early Roman dwellings were windowless huts. From the Etruscans, they learned to construct houses with fenestrae – windows.

The Etruscan term persona originally denoted a theatrical mask, representing the character or “person” an actor portrayed. This suggests Etruscan influence on Roman theatre, which would evolve into a significant aspect of Roman culture.

The former Etruscan walled town of Civitata di Bagnoregio. By Etnoy (Jonathan Fors) – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Today, this alphabet is known as the Roman alphabet, despite its Etruscan origins. However, due to the influence of Latin, this alphabet has been inherited by all Western European languages — including English.

The Romans of Latium embraced the Etruscan alphabet, along with their technology and cultural practices. However, the Etruscan civilization itself eventually faded. Etruscans are no longer to be found in modern Italy. What led to their disappearance?

Imperial Expansion and Standardization

Following the fratricide, Romulus became the first Rex, or King, of Rome. He was succeeded by six kings before a revolution brought an end to the monarchy.

During the monarchy, Rome was significantly influenced by its Etruscan neighbors. Trade flourished, and even some of Rome’s early kings were Etruscan. This foreign influence contributed to the monarchy’s downfall, as native Romans resented being ruled by Etruscan kings.

Despite being a monarchy, Rome had been gradually expanding its territory, eventually encompassing the Seven Hills of Rome within its walls. (The Roman Empire would not encircle the Mediterranean until approximately 70 AD.) Rome was steadily growing in power.

The last Roman Rex was an Etruscan named Tarquin the Proud. He was overthrown, marking the end of the monarchy. Rome transitioned from a Kingdom ruled by a Rex to a Republic.

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s 1867 painting of Rome’s last king, titled Tarquinius Superbus. By Lawrence Alma-Tadema – http://www.the-athenaeum.org/art/full.php?ID=1251, Public Domain.

The term Republic derives from two Latin words: Res (thing, affair) and Publica (the people). Thus, a Republic literally means “the People’s Affair.” It was a representative government led by two Consuls, elected by Roman citizens. Beneath the Consuls, a Senate composed of several hundred men played a crucial role. Legend dates the founding of the Republic to 509 BC, a date largely accepted by historians.

With the establishment of the Republic, Rome’s imperial expansion accelerated. From the 5th century BC onwards, Rome engaged in continuous warfare with neighboring communities. As Rome’s borders expanded, absorbing adjacent states, the Roman language gradually became dominant across the region. By 270 BC, Rome had firmly established itself as the undisputed power across the Italian peninsula.

This dominance elevated the Roman language, transforming it into a language of prestige and authority. It was now the language of the entire Latium region. Significantly, it was no longer referred to as the Roman language, but as the Latium language — that is, Latin.

The Spread of Latin and Language Shift

Millennia ago, modern-day Italy was a linguistically diverse landscape, populated by speakers of numerous languages, most of which have since vanished. How did these languages disappear, and how did their speakers come to adopt Latin?

It’s important to clarify how they did not learn Latin: through formal Latin schooling. Latin grammar books and dictionaries were nonexistent at this time, and Romans themselves did not teach Latin in schools. In fact, early Romans showed limited interest in writing during these centuries. The first identifiable Roman writers emerged only in the 3rd century BC, and their surviving works are mostly fragmentary.

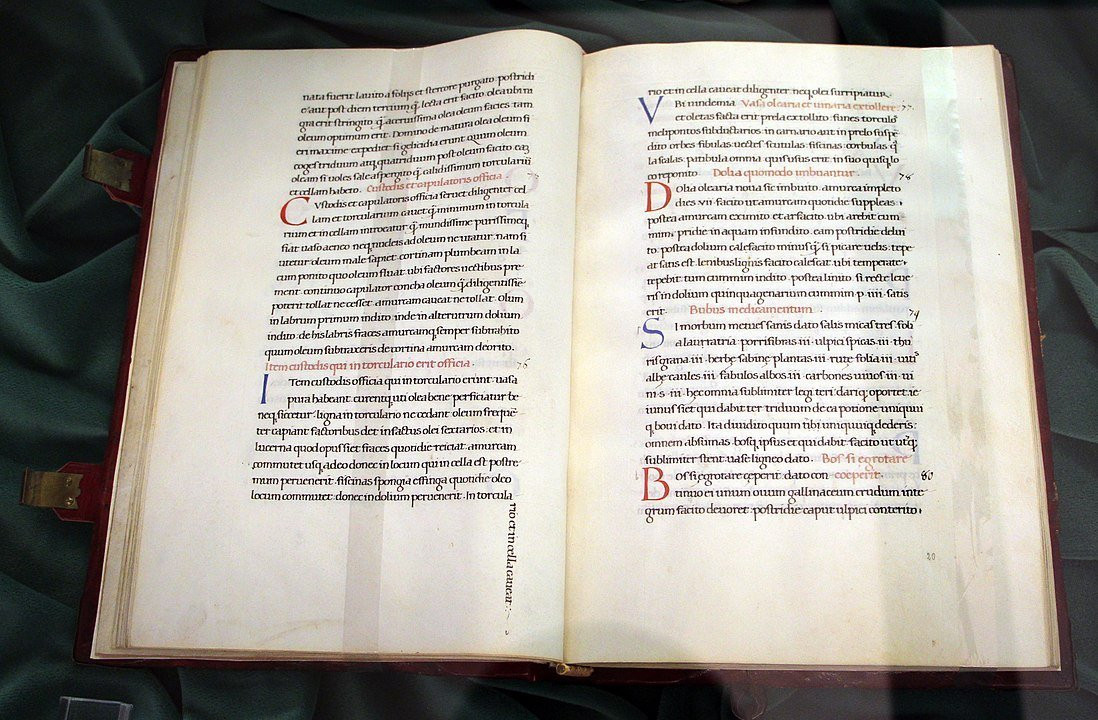

Image of the Latin text of Cato the Elder's "De Agri Cultura," showcasing early Latin writing.

Image of the Latin text of Cato the Elder's "De Agri Cultura," showcasing early Latin writing.

Cato the Elder’s De Agri Cultura. By Sailko – Own work, CC BY 3.0.

One of the earliest voices from Rome’s ancient past is Senator Marcus Porcius Cato, or Cato the Elder, who died in 149 BC. His book De Agri Cultura (On Agriculture) is among the oldest surviving books in Latin and offers valuable insights into early Roman values and practices.

Essentially, it’s a Roman homesteader’s manual, detailing everything from building an olive press to baking honey cakes. Cato’s work provides a glimpse into the values of ancient Romans. According to Cato, the highest praise for a Roman was to call him, “Bonum agricolam bonumque colonum!“

This translates to “A good farmer and a good husbandman!” For Romans like Cato, these were the most esteemed qualities.

How Latin Spread

Beyond agriculture, military service was a central aspect of ancient Roman life. Indeed, the spread of the Roman language across Latium was largely due to Roman prowess in both farming and warfare.

Following the conquest of new territories, land was often granted to Latin-speaking soldiers upon completion of their military service. These soldiers transitioned from military life to agriculture, settling with their families to cultivate the land and establish homes. This practice created “islands” of Latin speakers within other linguistic regions.

These Latin-speaking enclaves maintained connections with Rome while engaging in trade and social interactions with their non-Roman neighbors. As Latin was the language of power and commerce, conquered populations learned to adopt it. Over generations, Latin gradually became the common language of the people under Roman rule.

READ MORE: Is Latin a Dead Language?

This process resembles colonization. A soldier, miles in Latin, could become a colonus, or farmer. A group of such coloni formed a colonia, representing a community of Romans in a conquered territory. This is the origin of the English word “colony.”

Roman expansion led to the decline and disappearance of numerous languages. Traces of these lost languages occasionally appear in ancient Roman literature as isolated vocabulary items. Scholars have attempted to reconstruct some of these languages, but many remain largely unknown. The precise number of languages erased by Roman imperial expansion remains uncertain.

However, it is important to remember that early Italy was still remarkably diverse in terms of ethnicity, social structures, political organization, religion, and material culture. The gradual standardization of Latin, however, ultimately fostered a shared identity across Italy. One could argue that the standardization of Latin was instrumental in the very creation of a unified Italy.

The Greek Encounter and Classical Latin

While Latin became widespread, early Latin lacked literary sophistication. Before contact with Greece, Rome had produced no renowned poets, philosophers, or playwrights. Very little written Latin exists from before 200 BC, primarily inscriptions on gravestones and similar artifacts. Early Romans were not particularly focused on literary pursuits. Their strengths lay in farming and warfare.

These skills, however, were remarkably complementary. But in areas like literature, education, philosophy, science, art, and music, Roman contributions were initially limited. This would soon change dramatically.

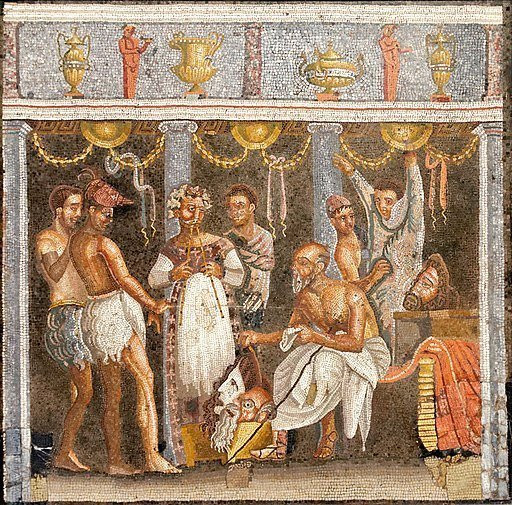

Roman actors in a mosaic from Pompeii. By Marie-Lan Nguyen (2011), Public Domain.

As Rome’s expansion continued, it encountered and eventually conquered Greece by 133 BC. Upon entering Greek cities, the Romans were astounded by the advanced Greek civilization. Greek architecture, sculpture, drama, and political thought represented a level of sophistication that Rome had not yet achieved. This encounter ignited a cultural transformation and a flourishing of the Latin language.

Initially, Roman culture heavily imitated Greek models. They adopted and adapted Greek culture for a Roman audience. The first literary form Romans borrowed from the Greeks was theatre, building upon their existing Etruscan-influenced theatrical traditions. Some of the earliest examples of Latin literature are plays written by Plautus around 200 BC.

Remarkably, the encounter between Greek and Latin was, in a sense, a family reunion. Linguists classify Latin and Greek as cognate languages, meaning they are linguistic siblings, descended from a common, older “mother” language. Neither language predates the other; instead, they share a common ancestor. The identity of this ancestral language remains unknown – perhaps it was among the languages lost due to imperial expansion.

Classical Latin and its Legacy

Latin was often contrasted with “barbarian” languages, but in its early stages, Latin itself was relatively unrefined. Before Greek influence, early Latin served primarily for warfare, trade, and law – a practical, direct, and somewhat unpolished language.

However, by emulating Greek culture, Latin writers began to explore literature, poetry, and rhetoric. They developed their artistic expression, discovering their own literary voice, and transforming Latin into a Classical Language, comparable to Greek in its sophistication and range.

The late Roman Republic witnessed significant advancements in the Latin language. Literary works emerged that demonstrated Latin’s capacity for eloquence, nuance, precision, and lyrical beauty.

The Romans themselves coined a term for the literature produced during this golden age. Drawing inspiration from the Greek word ἐγκριθέντες (encrithentes), meaning “select” or “approved,” they created the term classicus. Thus, Classical Latin was born.

For centuries, the works of the Classical period served as the standard for proper Latin, in contrast to Vulgar Latin, the spoken language of the common people. The first treatises on Latin grammar and spelling soon followed. One of the earliest was De Lingua Latina Libri XXV, a series of 25 books by the Roman scholar Marcus Terentius Varro in the 1st century BC. These efforts helped standardize Latin, slowing down its rate of linguistic change.

Latin the Living Dead Language

Centuries after Christ, Late Latin achieved parity with Greek as a language of literature, philosophy, science, and theology. Even after the collapse of the Roman Empire, Latin persisted. Although it ceased to be anyone’s first language, it remained the official language of educated discourse. Its rich literary and intellectual heritage made it too valuable to discard.

And even today, despite being labeled “dead” because it has no native speakers, Latin continues to endure remarkably well.

Inside St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. By SteO153 – Own work, CC BY-SA 2.5.

For modern individuals, learning Latin offers a unique connection to the past. Thousands of books in Latin have been produced throughout history, and only a fraction have been translated into English!

Latin also unlocks the door to understanding the Romance languages of the present! French, Spanish, Portuguese, Romanian, Italian, and many more are direct descendants of Latin. The linguistic similarities are so profound that learning Latin significantly accelerates the acquisition of any Romance language.

Despite no longer being a native tongue, Latin remains an official language in certain contexts. In Vatican City, the Roman Catholic Church continues to publish significant documents and decisions in Latin. As an international institution since the early Middle Ages, this practice helps transcend modern language barriers.

Finally, English stands to gain much from engaging with Latin, just as Latin benefited from its encounter with Greek. Although English is not a Romance language, it has been profoundly shaped by Latin over centuries. To a significant extent, English can be considered an adopted child of Latin! Maintaining this connection can enrich and enhance English as it continues to evolve.

Blake Adams is Latin Fellow at The Ancient Language Institute. He is a historian and Patristics scholar, and a graduate student at Wheaton College.

The Ancient Language Institute exists to aid students in the language learning journey through online instruction, innovative curriculum, and accessible scholarship about the ancient world and its languages. Are you interested in learning Latin?

Online Latin Courses

Bronze statue depicting the Capitoline Wolf suckling Romulus and Remus, symbolizing the legendary founders of Rome.

Bronze statue depicting the Capitoline Wolf suckling Romulus and Remus, symbolizing the legendary founders of Rome. Large golden broach, the Praeneste Fibula, displaying an early Latin inscription reading from right to left.

Large golden broach, the Praeneste Fibula, displaying an early Latin inscription reading from right to left. Ancient Etruscan hilltop town of Civita di Bagnoregio, showcasing Etruscan urban planning and architecture.

Ancient Etruscan hilltop town of Civita di Bagnoregio, showcasing Etruscan urban planning and architecture. Mosaic depicting Roman actors and musicians, illustrating the influence of Greek culture on Roman performing arts.

Mosaic depicting Roman actors and musicians, illustrating the influence of Greek culture on Roman performing arts. Photograph of the Latin phrase "Tu es Petrus et super hanc petram aedificabo ecclesiam meam" inside St. Peter's Basilica in Vatican City, highlighting the continued use of Latin.

Photograph of the Latin phrase "Tu es Petrus et super hanc petram aedificabo ecclesiam meam" inside St. Peter's Basilica in Vatican City, highlighting the continued use of Latin.