Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are, published in 1963, is not just a picture book; it’s a cultural phenomenon. Awarded the Caldecott Medal, the highest honor for US picture books, its impact on children’s literature and American culture is undeniable. Consider this: President Barack Obama, every year at the White House Easter Egg Roll, chose to read Where the Wild Things Are to children, a testament to its enduring appeal, even amidst a wealth of new children’s books (including those celebrating US-Canadian collaboration).

Close-up of the cover of "Where the Wild Things Are" book, featuring Max in his wolf suit looking towards the viewer, with a wild thing peeking from behind him.

Close-up of the cover of "Where the Wild Things Are" book, featuring Max in his wolf suit looking towards the viewer, with a wild thing peeking from behind him.

With over 19 million copies sold globally and translations into more than 40 languages, Where the Wild Things Are resonates deeply across cultures. Sendak himself famously said, “I don’t write for children. I write, and somebody says ‘it’s for children,’” a quote often cited yet perhaps overshadowing his Caldecott acceptance speech where he stated, “Where the Wild Things Are wasn’t meant to please everyone. Only children.” This duality highlights the book’s complex nature, appealing directly to the child’s perspective while sparking debate and analysis among adults.

Let’s delve into what makes this book so enduring, exploring its genius through a close examination of its pages.

Analyzing the Opening: Tantrum and Restraint

The book begins with immediate action, plunging us into Max’s world of mischief.

First spread of "Where the Wild Things Are", showing Max hammering a nail into the wall, teddy bear hanging from a coat hanger, text on the left page and illustration on the right.

First spread of "Where the Wild Things Are", showing Max hammering a nail into the wall, teddy bear hanging from a coat hanger, text on the left page and illustration on the right.

The opening spread shows Max in the midst of a tantrum, scowling as he hammers a nail into the wall, a teddy bear dangling precariously. The layout is traditional: text on the left, illustration on the right. This formal structure starkly contrasts with the chaotic emotion depicted. The generous white space surrounding the relatively small illustration on the first page is crucial. It creates a feeling of confinement, emphasizing Max’s pent-up frustration and setting a tone of deliberate unease for the reader.

This initial restraint in the visual space is quickly broken as Max’s wildness escalates.

The white space diminishes in the subsequent spread, allowing the image to expand. This visual growth mirrors Max’s escalating behavior. He is now chasing a dog with a fork, an act of playful aggression. Notably, Max is running in the opposite direction from the previous page, enhancing the sense of undirected energy and domestic chaos. The dog itself bears a striking resemblance to Maurice Sendak’s own dog, Jennie, adding a personal touch to the illustration.

Close-up portrait of a Jennie dog, similar to the dog chased by Max in "Where the Wild Things Are", showcasing its distinctive features.

Close-up portrait of a Jennie dog, similar to the dog chased by Max in "Where the Wild Things Are", showcasing its distinctive features.

The Off-Screen Discipline and Onset of Fantasy

The narrative jumps ahead, omitting the immediate parental reaction to Max’s rampage, amplifying the emotional impact.

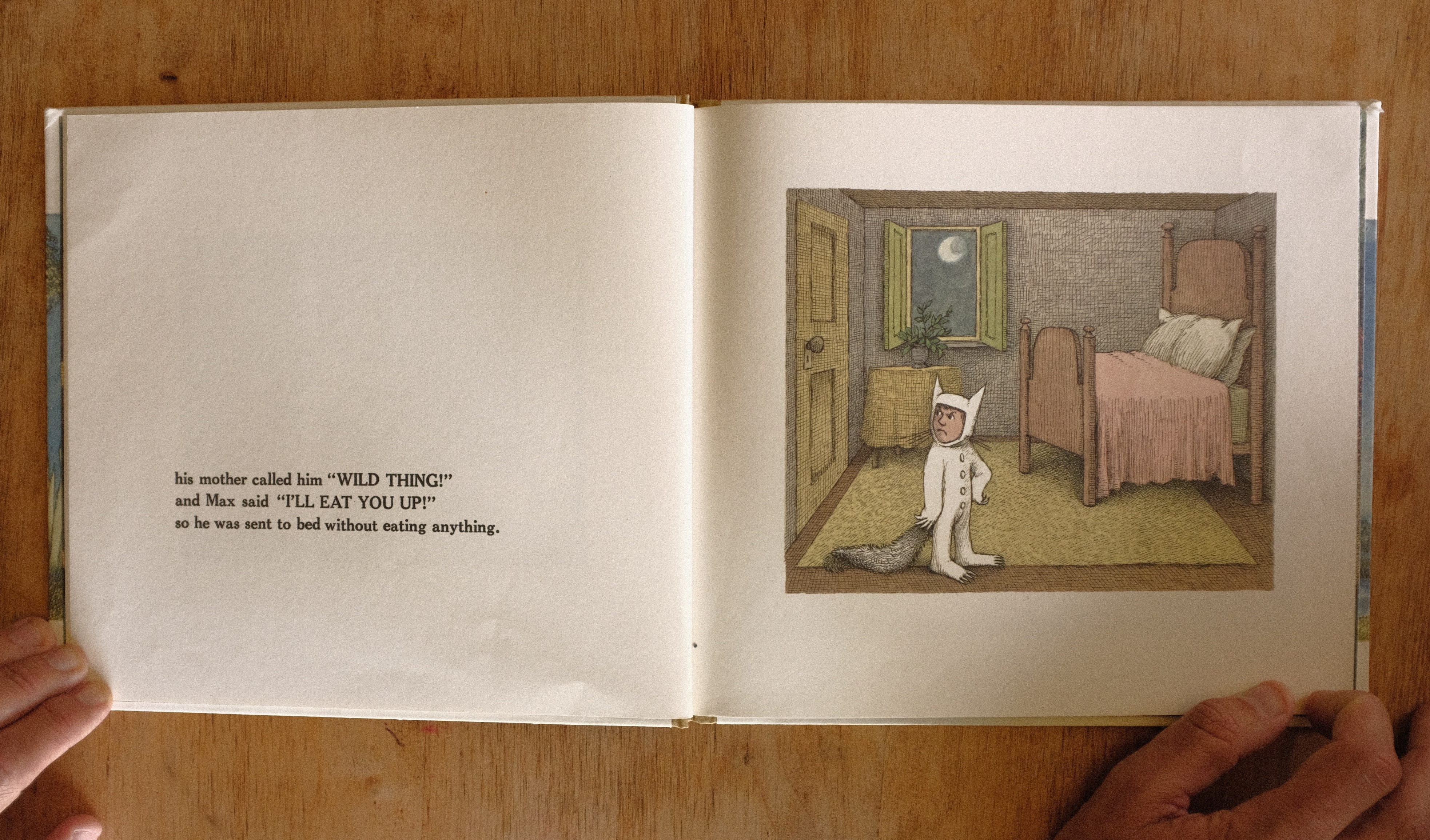

Third spread of "Where the Wild Things Are", showing Max in his room, door closed, illustration filling more of the page, implying a passage of time and consequence.

Third spread of "Where the Wild Things Are", showing Max in his room, door closed, illustration filling more of the page, implying a passage of time and consequence.

We find Max in his room, the door now closed. A significant moment occurs “off-screen”: Max’s mother, having had enough, sends him to bed without supper. This crucial event is conveyed solely through text. She calls him “WILD THING!”, and in defiance, Max retorts, threatening to eat her. This intense exchange, marked by the book’s only instance of all-caps, underscores the severity of their conflict.

The illustration of Max’s room is telling. It’s sterile and impersonal, more like a bland bed and breakfast than a child’s vibrant space. This detail speaks volumes about Max’s home environment, suggesting a lack of warmth or understanding that might fuel his rebellious behavior and desire to escape into fantasy. It’s no surprise that a forest begins to grow in this emotionally barren space.

A collection of toys and figurines, representing the kind of playful environment that contrasts with Max's sterile room in "Where the Wild Things Are".

A collection of toys and figurines, representing the kind of playful environment that contrasts with Max's sterile room in "Where the Wild Things Are".

The Forest, the Boat, and the Journey to the Wild Things

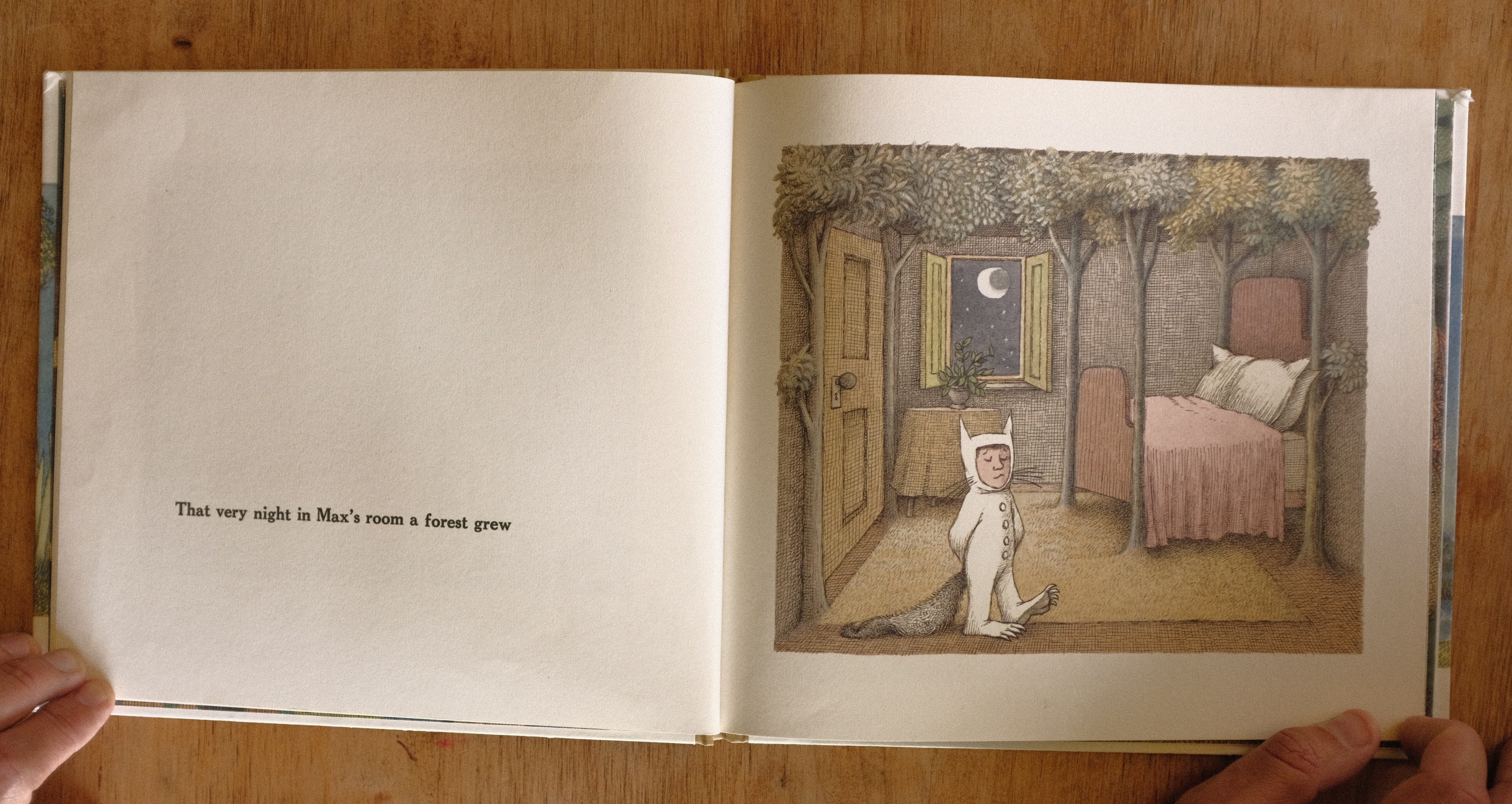

As Max’s imagination takes over, the illustrations expand, mirroring his burgeoning fantasy world.

Fourth spread of "Where the Wild Things Are", a forest growing in Max's room, illustration filling the entire page, showcasing the transition from reality to fantasy.

Fourth spread of "Where the Wild Things Are", a forest growing in Max's room, illustration filling the entire page, showcasing the transition from reality to fantasy.

The forest in Max’s room grows, and the illustrations become “full bleed,” completely filling the pages.

Fifth spread of "Where the Wild Things Are", Max's boat sailing, illustration crossing the gutter, symbolizing the complete immersion into the fantasy world.

Fifth spread of "Where the Wild Things Are", Max's boat sailing, illustration crossing the gutter, symbolizing the complete immersion into the fantasy world.

Then, remarkably, the illustration crosses the gutter, the central divide between the two pages. This visual technique emphasizes the immersive nature of Max’s fantasy, where the pictures literally break free from the constraints of the page and invade the space of the words. Sendak manipulates both space and time. Max’s journey “through night and day and in and out of weeks and almost over a year . . .” is compressed into a few pages, highlighting the subjective nature of childhood experience.

Sixth spread of "Where the Wild Things Are", Max arriving at the island of the wild things, illustration continuing to dominate the page, hinting at the fantastical creatures to come.

Sixth spread of "Where the Wild Things Are", Max arriving at the island of the wild things, illustration continuing to dominate the page, hinting at the fantastical creatures to come.

“. . . to where the wild things are.” This sentence, ending with only the second period in the entire book, marks a significant shift. We’ve traversed emotional turmoil, domestic conflict, and a fantastical journey in just two sentences, a testament to Sendak’s narrative efficiency.

The Wild Rumpus and the Shift in Power

Upon arriving at the island where in the wild things are, the book’s design changes again.

Full-bleed illustrations now span both pages, with text relegated to a white bar at the bottom. As Max becomes “king of all wild things,” the illustrations grow even larger, the white bar shrinks, culminating in the famous line: “‘And now,’ cried Max, ‘let the wild rumpus start.’”

The rumpus unfolds across three wordless, full-bleed spreads. The absence of text amplifies the wildness, the visual storytelling taking center stage.

Tenth spread of "Where the Wild Things Are", concluding wild rumpus, the final full two-page illustration without text, bringing the wild dance to a climax.

Tenth spread of "Where the Wild Things Are", concluding wild rumpus, the final full two-page illustration without text, bringing the wild dance to a climax.

Ambiguity and the Return Home

The rumpus ends abruptly, and words return, marking another significant shift in the narrative.

Max, now in control, sends the wild things to bed without supper, mirroring his mother’s earlier discipline. He decides to return home. The reason for Max’s change of heart remains ambiguous. The text suggests loneliness, contrasting “where the wild things are” with “where someone loved him best of all.”

However, the illustration offers a deeper insight. Max’s expression here is remarkably nuanced, a departure from his previously exaggerated emotions. He appears almost adult-like, perhaps reflecting disappointment, boredom, or even regret. This ambiguity is a strength of picture books, conveying complex emotions beyond words. It’s a moment of reflection, where Max seems to embody his mother, echoing her earlier actions.

As Max sails home, the wild things’ emotions are equally ambiguous. The text states they are sad, wanting him to stay, but their expressions in the illustration are less clear, almost vacant, suggesting they might be already reverting to their mindless wildness.

Back to Reality, and a Hot Supper

The journey home mirrors the journey to the island, with shrinking illustrations and growing white space, returning Max to “his very own room.”

Thirteenth spread of "Where the Wild Things Are", Max back in his room, full-bleed illustration with text, showing his return to reality but with a changed perspective.

Thirteenth spread of "Where the Wild Things Are", Max back in his room, full-bleed illustration with text, showing his return to reality but with a changed perspective.

The layout returns to words on the left, illustration on the right, but now the illustration is full-bleed, signifying that Max’s world has expanded. The room itself feels subtly different, more relaxed, reflecting Max’s internal shift.

The moon outside Max’s window is full, a detail that confounds a simple “it-was-all-a-dream” interpretation. It suggests a passage of time in Max’s fantasy world, contrasting with the immediate warmth of his supper. This ambiguity is deliberate, a hallmark of Sendak’s genius, embracing contradiction and reflecting the complexities of childhood reality.

The final page turn is startling and perfect.

Fourteenth spread of "Where the Wild Things Are", a blank page with only text "and it was still hot.", emphasizing the unseen mother and the resolution.

Fourteenth spread of "Where the Wild Things Are", a blank page with only text "and it was still hot.", emphasizing the unseen mother and the resolution.

“and it was still hot.” Five words on a blank page. The absence of illustration is powerful. It’s as close as we get to seeing Max’s mother, her presence implied in the act of preparing and leaving the hot supper. It’s a gesture of forgiveness and unconditional love.

Max never apologizes, and neither does his mother explicitly apologize for sending him to bed. This radical notion, that a child doesn’t need to change to deserve love, is profoundly moving. Where the Wild Things Are culminates in a state of grace, a quiet understanding and acceptance.

Final image of "Where the Wild Things Are" book, showcasing the cover again, reinforcing the iconic status of the book.

Final image of "Where the Wild Things Are" book, showcasing the cover again, reinforcing the iconic status of the book.

Where the Wild Things Are remains a masterpiece because of its artistic brilliance, emotional depth, and its honest portrayal of childhood emotions. It’s a book that speaks to children on their level, acknowledging the wildness within while offering the comforting assurance of unconditional love.