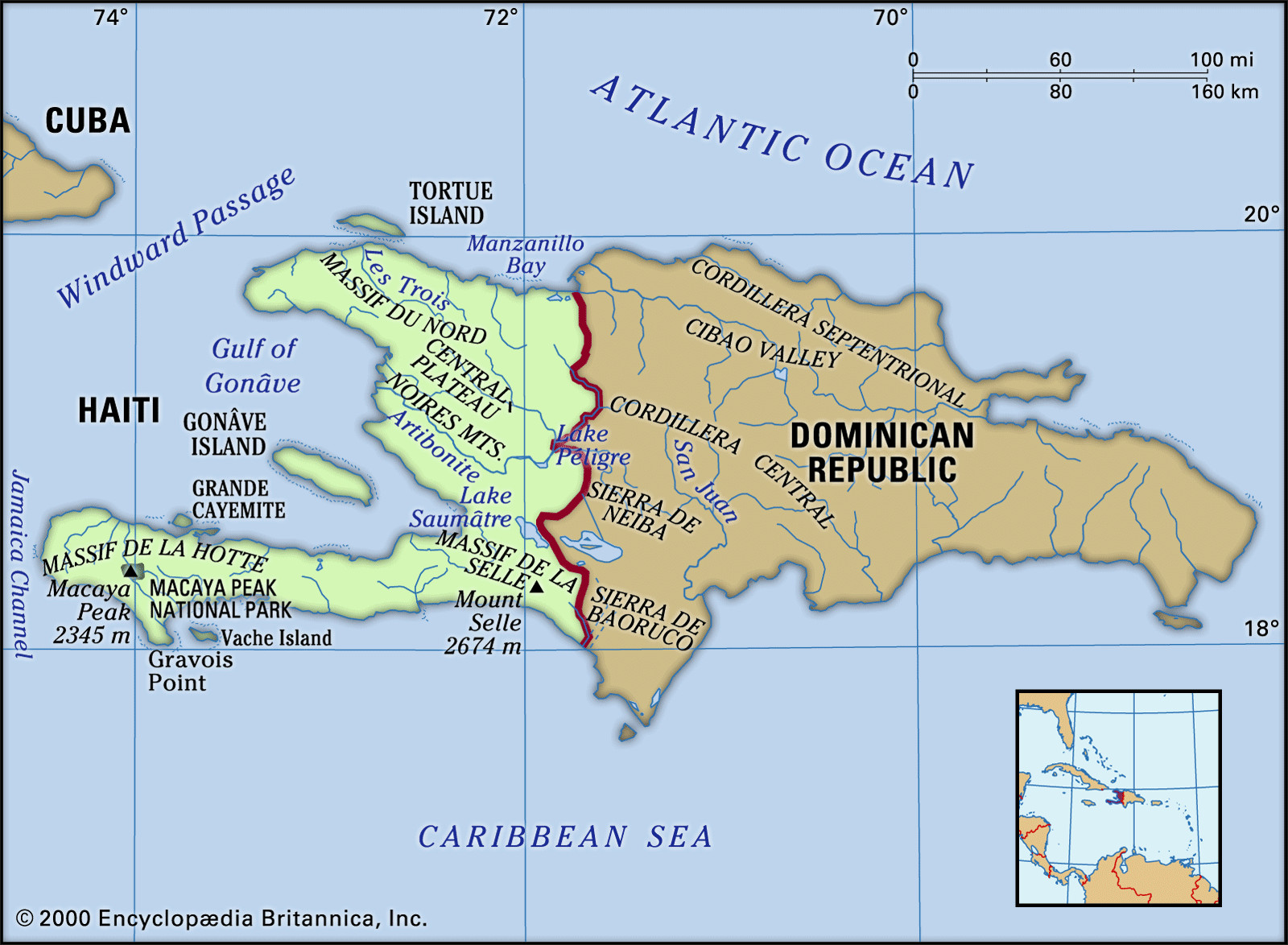

Haiti, a nation rich in history and culture, often sparks curiosity about its precise location. Situated in the Caribbean archipelago, Haiti occupies the western, smaller portion of the island of Hispaniola. Sharing Hispaniola with the Dominican Republic to its east, Haiti is nestled between the Caribbean Sea to the south and west and the vast Atlantic Ocean to its north. This strategic position places Haiti approximately 50 miles (80 km) west of Cuba, across the Windward Passage, a key waterway linking the Atlantic and Caribbean. Jamaica lies roughly 120 miles (190 km) west of Haiti’s southern peninsula, separated by the Jamaica Channel. To the north, Great Inagua Island, part of The Bahamas, is about 70 miles (110 km) away. Adding to its insular geography, Haiti asserts claim over Navassa Island, a small, uninhabited islet administered by the U.S., located about 35 miles (55 km) west in the Jamaica Channel. Understanding Haiti’s location on the map reveals its Caribbean identity and proximity to major islands and maritime routes.

Unveiling Haiti’s Terrain: Relief and Drainage

The name Haiti itself, derived from the Indigenous Arawak term “Ayti,” meaning “Mountainous Land,” aptly describes the country’s rugged topography. Approximately two-thirds of Haiti’s land rises above 1,600 feet (490 meters), contributing to its dramatic landscapes. Haiti’s coastline is characterized by two peninsulas, a longer one extending southward and a shorter one to the north, which together define the triangular Gulf of Gonâve. Within this gulf lies Gonâve Island, encompassing about 290 square miles (750 square km). Haiti’s shores are predominantly rocky, edged with cliffs, and feature several excellent natural harbors. The seas surrounding Haiti are famed for their vibrant coral reefs. Plains, while limited, are crucial as the most fertile agricultural areas and, consequently, the most densely populated regions. Haiti is traversed by numerous rivers, though they are generally short and non-navigable.

The island of Hispaniola is structured around four major mountain ranges running east to west, and these form the geographical backbone of Haiti. The northernmost range, the Cordillera Septentrional in the Dominican Republic, touches Haiti only on Tortue Island, situated off the northern coast. Tortue Island, spanning about 70 square miles (180 square km), historically served as a 17th-century haven for privateers and pirates. The second significant range, Haiti’s Massif du Nord, is a series of parallel chains known as the Cordillera Central in the Dominican Republic. This massif averages around 4,000 feet (1,200 meters) in elevation. Perched atop one of its peaks, overlooking Cap-Haïtien and the narrow coastal plain, stands the Citadel Laferrière, a fortress constructed in the early 19th century by Haitian ruler Henry Christophe.

Moving inland, the Central Plateau, or San Juan Valley in the Dominican Republic, occupies about 150 square miles (390 square km) in Haiti’s center. This plateau, averaging 1,000 feet (300 meters) high, is somewhat isolated, accessed via winding roads. It is bordered by the Cahos Mountains and the Noires Mountains to the west and south, respectively. The Artibonite River, Hispaniola’s longest at approximately 175 miles (280 km), originates in the Dominican Republic’s Cordillera Central and flows southwest along the Haitian border. Its tributaries flow through Haiti’s Central Plateau, joining the main river as it turns westward towards the Gulf of Gonâve, skirting the Noires Mountains. Lake Péligre, a reservoir formed by damming the Artibonite in eastern Haiti in the mid-20th century, powers a hydroelectric complex operational since 1971, though its output can fluctuate with seasonal dryness. Upstream from the Artibonite’s delta in the Gulf of Gonâve, water is diverted to irrigate the Artibonite Plain.

Further south, the Matheux Mountains in west-central Haiti and the Trou d’Eau Mountains to the east correspond to the Sierra de Neiba in the Dominican Republic. This range forms the northern edge of the narrow Cul-de-Sac Plain, adjacent to Port-au-Prince and home to the brackish Lake Saumâtre on the Dominican border. South of the Cul-de-Sac Plain lies the Massif de la Selle, or Sierra de Baoruco in the Dominican Republic, reaching Haiti’s highest point at Mount Selle, towering at 8,773 feet (2,674 meters). The Massif de la Hotte, the western extension of this range on the southern peninsula, culminates in Macaya Peak at 7,700 feet (2,345 meters). The Cayes Plain stretches along the coast southeast of Macaya Peak.

Geological Composition and Seismic Activity

Haiti’s mountainous terrain is primarily composed of limestone, with some volcanic formations, particularly in the Massif du Nord. Karstic landscapes, characterized by limestone caves, grottoes, and underground rivers, are common across the country. A significant fault line runs across the southern peninsula, passing just south of Port-au-Prince, making Haiti susceptible to frequent seismic events. Earthquakes have historically devastated Haitian cities, with Cap-Haïtien destroyed in 1842 and Port-au-Prince in 1751 and 1770. The catastrophic earthquake of January 2010 and subsequent aftershocks inflicted immense damage on Port-au-Prince and surrounding areas. Buildings, including critical infrastructure like the National Palace, the city’s cathedral, and hospitals, collapsed. The death toll was estimated to exceed 200,000, with hundreds of thousands injured and over a million left homeless. Léogâne, located west of the capital near the earthquake’s epicenter, was almost entirely destroyed.

Soil Conditions and Environmental Challenges

The mountainous soils of Haiti are generally thin and quickly lose fertility upon cultivation. Red clays and loams cover the lower hills, while the plains and valleys possess fertile alluvial soils, which are, however, often overcultivated due to high population density. Deforestation has led to severe soil erosion, with estimates suggesting that up to one-third of Haiti’s land has been irreversibly eroded. This environmental degradation poses significant challenges to Haiti’s agricultural sustainability and overall ecological health.

In conclusion, Haiti’s location on the western side of Hispaniola in the Caribbean defines its island nation status. Its mountainous terrain, as reflected in its indigenous name, shapes its landscape and influences its climate and land use. Understanding Haiti’s geographical context is crucial to appreciating its environmental and societal challenges, as well as its unique place in the Caribbean region.

Haiti earthquake of 2010

Haiti earthquake of 2010