Prince Rogers Nelson, an iconic figure in music history, was born on June 7, 1958. But Where Is Prince From? He hailed from Minneapolis, Minnesota, a city that, contrary to common perception, boasts a vibrant and intricate cultural history. This unique environment profoundly influenced the young artist, shaping his perspectives and ultimately his groundbreaking musical career.

The Prince Rogers Trio / Photo by John F. Glanton, courtesy Hennepin County Library

The Prince Rogers Trio / Photo by John F. Glanton, courtesy Hennepin County Library

Mattie Shaw and Prince / Copyright The Prince Estate

Mattie Shaw and Prince / Copyright The Prince Estate

Prince’s parents, John Lewis Nelson and Mattie Della Shaw, were drawn together by their shared love for music. They honored this connection when naming their son, giving him John’s stage name, Prince Rogers.

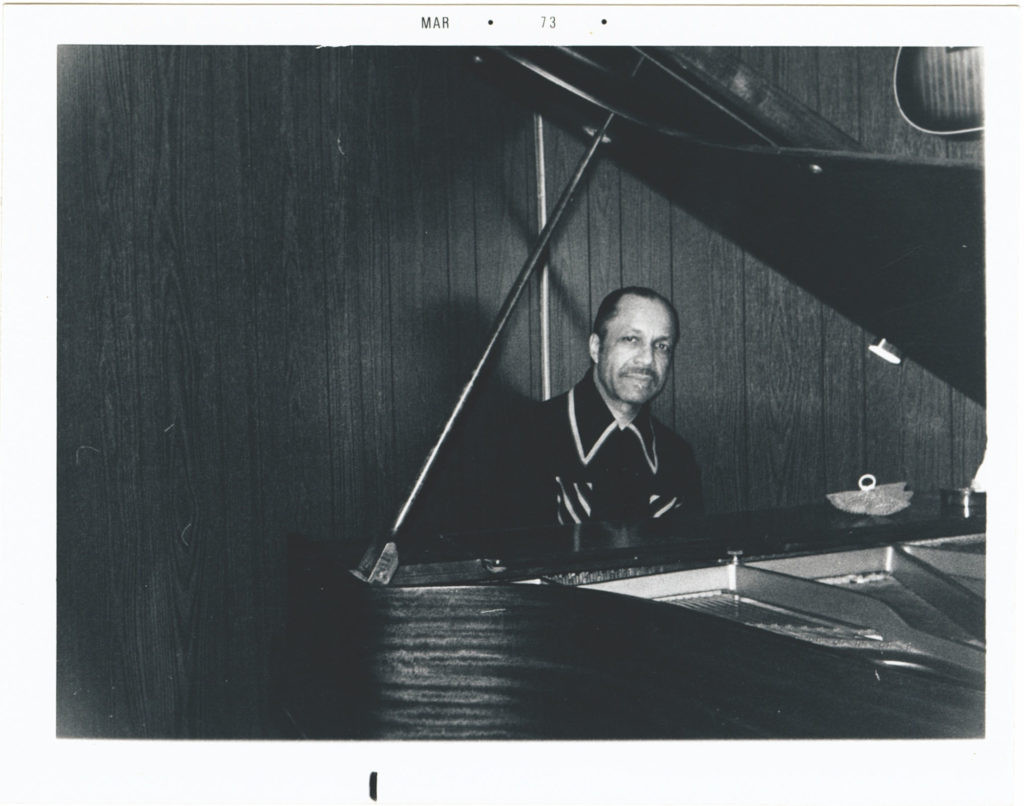

In the 1950s, John Nelson was a respected figure in the local music scene, known for his piano skills and leadership of the Prince Rogers Trio. This jazz ensemble regularly performed in clubs and community spaces on Minneapolis’s North Side, including the Phyllis Wheatley House, a significant historical landmark established in 1924 to support African-American families migrating to North Minneapolis. It was at the Blue Note jazz club, during one of his trio’s performances, that John met Mattie, who he then recruited as a vocalist for his band. Their musical partnership blossomed into romance, and almost nine months after their wedding on August 31, 1957, they welcomed Prince into the world.

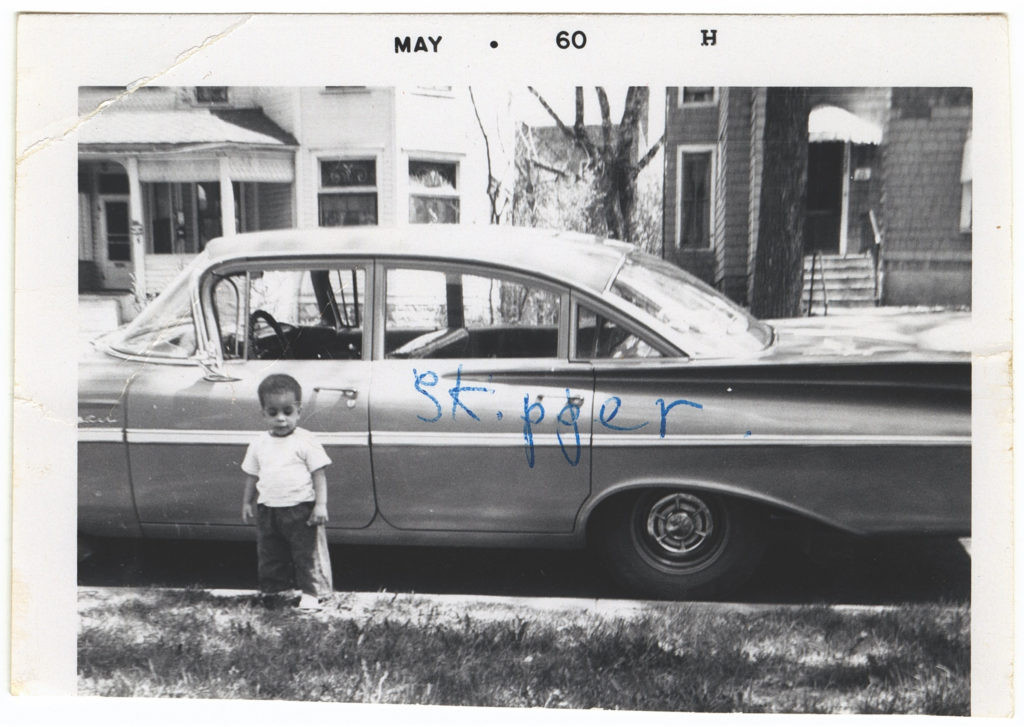

Prince himself reflected on his upbringing, writing in his memoir, The Beautiful Ones, about the dynamic within his childhood home. He described “2 Princes in the house where we lived,” distinguishing between his father, “the older one with all the responsibilities of heading a household,” and himself, “the younger one whose only modus operandi was fun.” In his early years, Prince was often called by his nickname, Skipper.

From a very young age, Prince recalled being immersed in music at home. During his introspective Piano and a Microphone concert at Paisley Park on January 21, 2016, he began the show with a childhood memory of being captivated by his father’s piano at just three years old. He recounted his young self thinking, “Here comes dad… I’m not supposed to touch his piano… but I want to play it so bad.”

When Prince was seven, his parents, John and Mattie, separated and eventually divorced. Reflecting on this significant life change as he began writing his memoir in early 2016, Prince noted, “Eye had no idea what impact that would have on me. Eye was 7 years old & more than anything Eye just wanted peace. A quiet space where Eye could hear myself think & create.” After John moved out, Prince found the freedom to explore the piano himself, initially picking out melodies from television theme songs like Batman and The Man from U.N.C.L.E. He remembered questioning his ability compared to his father, wondering, “I can’t play piano like dad, though—how does dad do that?”

John L. Nelson / Copyright The Prince Estate

John L. Nelson / Copyright The Prince Estate

Skipper / Copyright The Prince Estate

Skipper / Copyright The Prince Estate

As Prince grew older, his perspective on his father’s musical talent shifted from intimidation to inspiration. At age 12, during a period living with his father, he observed firsthand how John balanced a daytime job at Honeywell with his passion for music, playing late-night gigs and constantly creating.

Prince shared a story his father told him about these musical urges: “He told me one time that he has dreams where he’d see a keyboard in front of his eyes and he’d see his hands on the keyboard and he’d hear a melody. And he can get up and it can be like 4:30 a.m. and he can walk right downstairs to his piano and play the melody,” Prince recounted in a 1981 interview with Musician Magazine (published in 1983). “And to me that’s amazing because there’s no work involved really; he’s just given a gift in each song.”

When Prince rose to international fame with the film Purple Rain in 1984, many assumed the movie was a straightforward biography of his early life. However, Prince clarified that Purple Rain was only partially based on real events and contained significant dramatization. One genuine parallel was the shared drive for constant musical creation between Prince and his father, fostering a unique creative bond. They collaborated on notable songs like “Computer Blue” and “Father’s Song” from Purple Rain, and “The Ladder” from Around the World in a Day.

“We have the same hands. We have the same dreams. We write the same lyrics, sometimes. Accidentally, though. I’ll write something and then I’ll look up and he’ll have the same thing already written,” Prince told Ebony in 1986. Thirty years later, at his Paisley Park piano, he summarized their complex relationship simply: “I thought I’d never be able to play like my dad, and he never missed an opportunity to remind me of that,” he stated. “But we got along good. He was my best friend.”

From Child Prodigy in Minneapolis to Bandleader

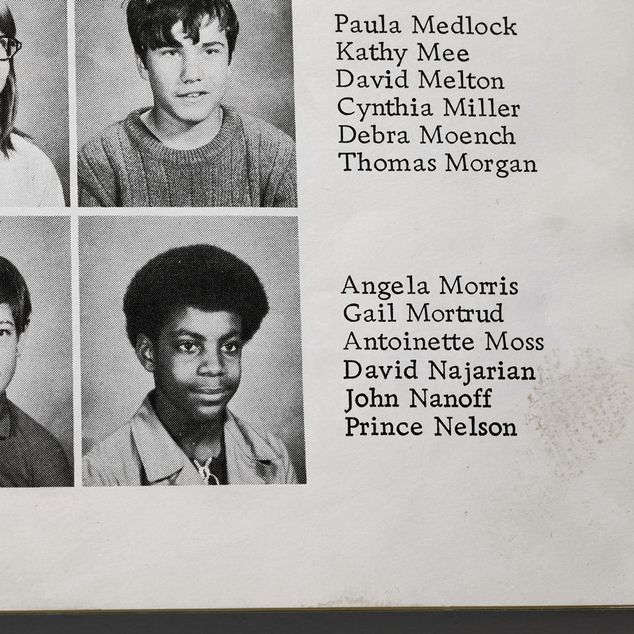

Bryant Junior High yearbook 1972

Bryant Junior High yearbook 1972

Entering junior high, Prince expanded his interests beyond music. He participated in baseball, football, and basketball teams at school alongside his step-brother, Duane. Sports and music provided stability during a turbulent period in Prince’s life. His mother, Mattie, had remarried, and Prince struggled to adjust to his new stepfather, Hayward Baker. He first ran away from home during junior high, later admitting to Ebony, “I think maybe I was too much of a punk back then to deal with the situation I was in.” For several years, he moved between his father’s residence in North Minneapolis, his aunt’s house in South Minneapolis, and a home where he formed his first significant creative partnership and rehearsed extensively with his initial band.

Prince spent most of 7th and 8th grade at Bryant Junior High School in South Minneapolis. However, during a brief period at Lincoln Junior High near his father’s North Minneapolis home at the start of 7th grade, he met André Anderson, later known as André Cymone. Discovering their shared passion for music, Prince and André quickly became close friends, spending after-school hours jamming on instruments at Prince’s father’s apartment.

André Cymone recalled their early musical connection: “He sat at his father’s piano and played several television and movie theme songs. I played along on a large-scale ukulele, I think for the first time in his life — and I know for the first time in mine — we found someone in each other who took music and all its possibilities extremely seriously. I think, after that day, we were pretty much inseparable. We hung out all the time.”

They soon discovered their families had long-standing connections. Their mothers were friends for years, and André’s father, Fred Anderson, had been a member of the Prince Rogers Trio. The families’ paths initially crossed at church.

“We grew up 1st attending 7th Day Adventist Church where Eye 1st met the Andersons,” Prince wrote in The Beautiful Ones. “Fred Anderson and his wife Bernadette were friends of my parents and, though Eye never asked, Eye believe now that Bernadette & my mother secretly had each other’s back when it came 2 their husbands. 4 that matter Eye think that the entire planet has been maintained this long by the feminine principle. Eye can always let my guard down when there’s a woman present.”

Bernadette Anderson had a lasting positive influence on Prince. When he began his memoir, he intended to dedicate an entire chapter to her. After a short period with his aunt, Olivia Lewis, in South Minneapolis, a teenage Prince moved in with Bernadette and her six children. She became a crucial guiding figure, so much so that “Queen Bernie,” as she was known locally, received a shout-out in Prince’s autobiographical 1992 song “The Sacrifice of Victor”: “Bernadette’s a lady, and she told me / ‘Whatever you do son, a little discipline is what you need / You need to sacrifice.’”

André Cymone emphasized Bernadette’s role: “Prince and my mother, they were quite close — they were really, really close. After all she was responsible for him and his well-being during probably his most formative years. My mother’s main demand and his main responsibility was to help around the house and make it to school on time and maintain good grades. I think that was it, and he did that. That’s what he did.”

At Central High School, Prince was known by classmates as a talented and dedicated musician. By sophomore year, he had quit the basketball team to devote all his free time to music in the school music room. He avoided joining the school band or taking formal lessons, a detail highlighted in his first press mention, a 1976 article in the Central High Pioneer student newspaper: “He likes Central a great deal, because his music teachers let him work on his own.” Instead, Prince preferred learning from their stereo, spending hours with André in the Anderson’s basement listening to rock and folk artists like Joni Mitchell, Maria Muldaur, and Carlos Santana on FM station KQRS. They also explored the rich history of R&B, soul, and funk via KUXL, a black community AM radio station broadcasting to North Minneapolis.

Prince recalled his KUXL listening habits at his January 2016 Piano and a Microphone show:

“Back then, radio was localized. We had a DJ named Pharaoh Black, and Kyle Ray, and Jack Harris. Jack Harris had his own band, that’s how funky he was. He would choose what we listened to, and he had great taste.”

From Grand Funk Railroad to Sly and the Family Stone, Jimi Hendrix to the Jackson 5, Prince absorbed a wide range of musical styles. His band, Grand Central, began securing gigs beyond North Minneapolis community centers, playing at high school proms and homecoming dances across the city. Prince recognized the need to learn Top 40 hits to appeal to diverse audiences.

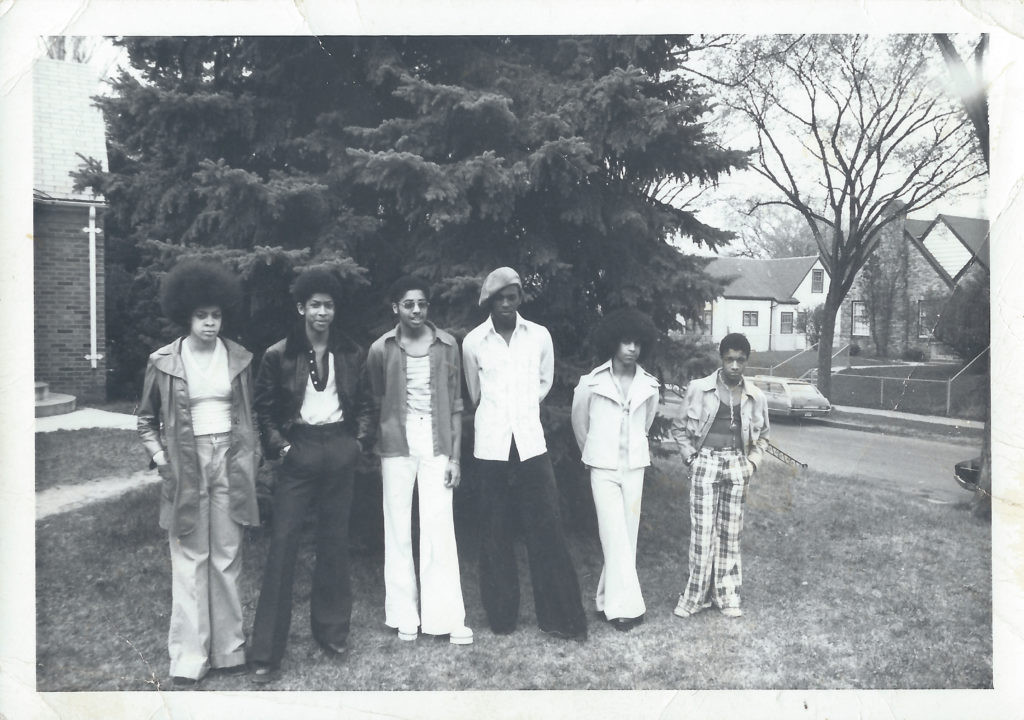

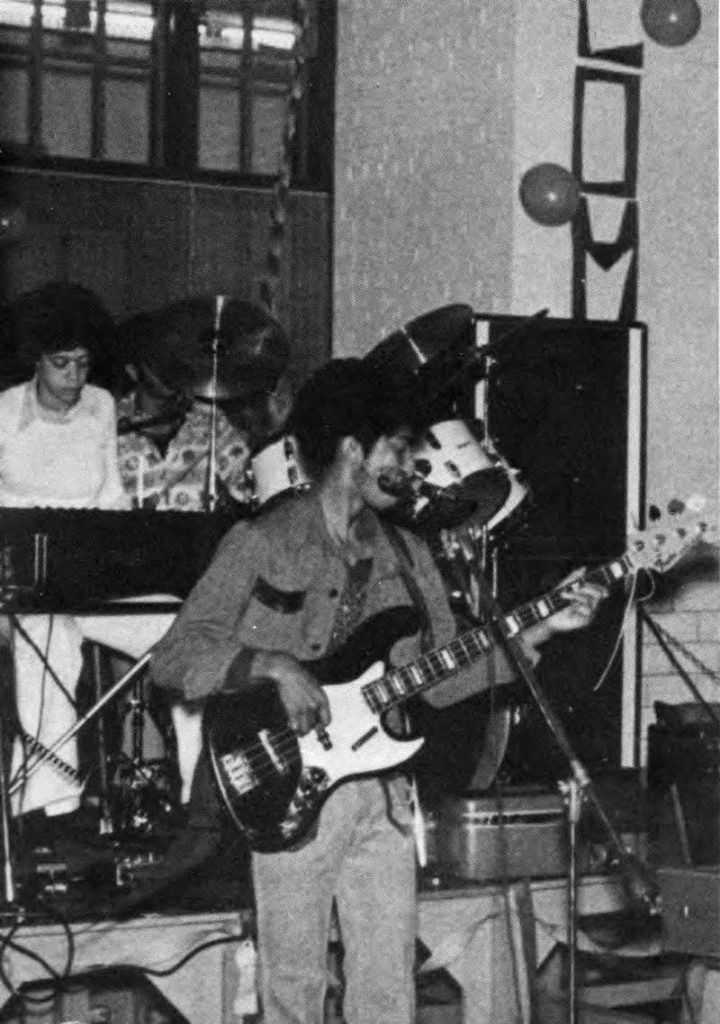

Grand Central

Grand Central

Grand Central’s lineup evolved over time. The initial members were Prince, André Anderson, and Prince’s cousin, Charles “Chazz” Smith. Later additions included André’s sister, Linda Anderson, on organ, Terry Jackson and William Doughty on percussion, and in 1974, Morris Day replaced Smith on drums. The band rapidly became a popular act on the North Side.

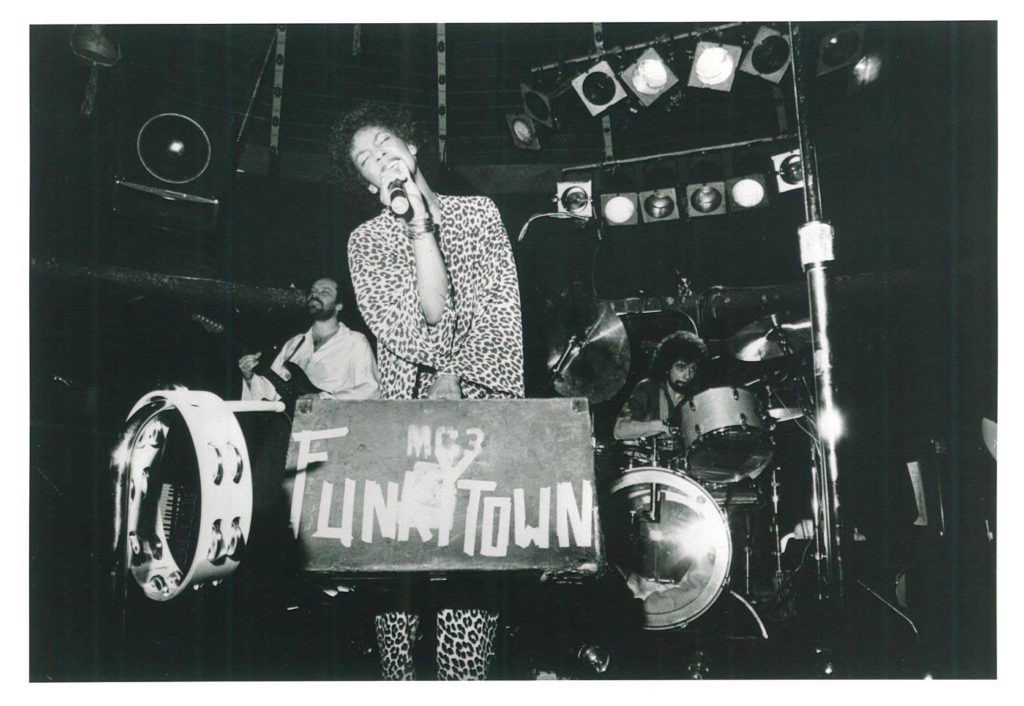

Grand Central competed in neighborhood Battle of the Bands events at venues like the Phyllis Wheatley and The Way community centers. They faced bands like The Family, led by Sonny Thompson, a future New Power Generation member and early Prince mentor; Flyte Tyme, featuring Terry Lewis, David Eiland, and Cynthia Johnson (who sang the Lipps Inc. hit “Funkytown”); Mind and Matter, led by Jimmy Jam; and Cohesion.

“We jammed a lot with other bands,” Prince told the Aquarian Night Owl in 1981. “There was a lot of competition around ’75. It was a time when there was a lot of spirit. I think that helped me come out of myself. We got in a lot of trouble from other band members if we copied anything [from them], and we gave them a lot of trouble if they copied anything [from us], so it was a real competitive thing. You had to be as out as you could and as different, and as much you as possible.”

During these formative years in Minneapolis, Prince began to define his signature sound, a blend of black and white musical influences bridging funk and rock, punk and disco, modern dance music, and classic jazz and blues. By high school graduation, Prince was well on his way to developing the Minneapolis Sound and preparing to break out beyond Minnesota.

Grand Central playing Central High Prom / Photo from Central High yearbook, 1976

Grand Central playing Central High Prom / Photo from Central High yearbook, 1976

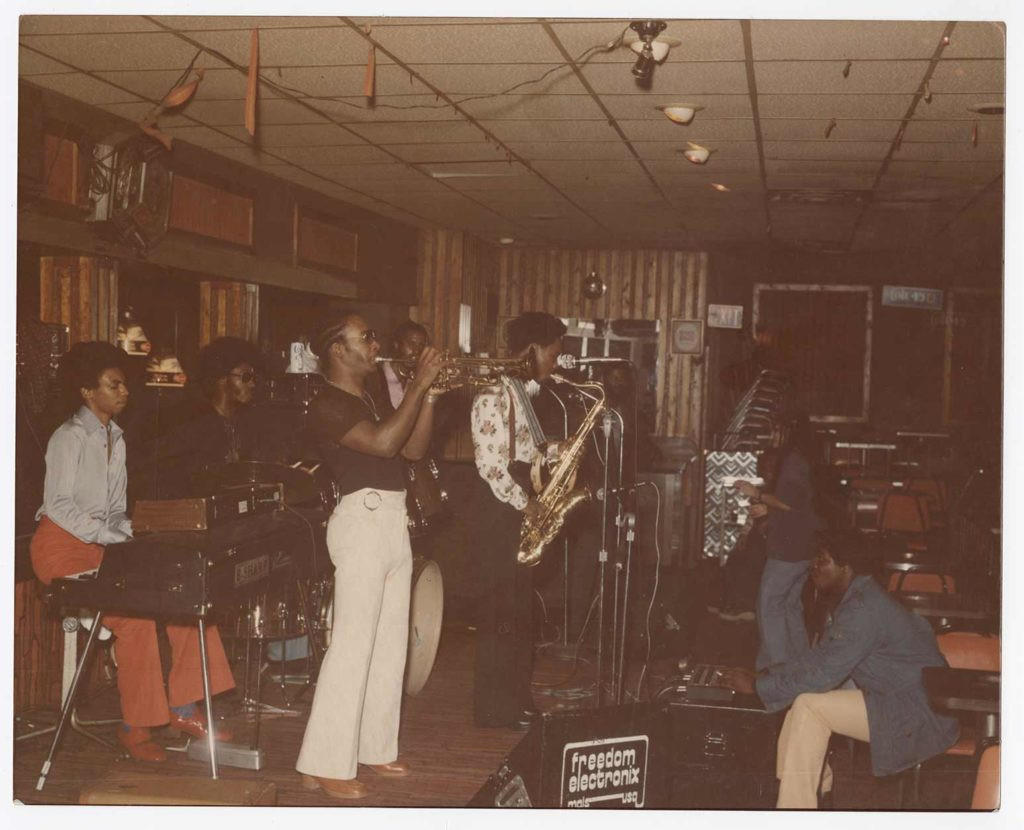

The Way / Photo courtesy Minnesota Historical Society

The Way / Photo courtesy Minnesota Historical Society

Terry Lewis and Cynthia Johnson – Flyte Tyme / Photo by Charles Chamblis

Terry Lewis and Cynthia Johnson – Flyte Tyme / Photo by Charles Chamblis

The Family at The Walker Center

The Family at The Walker Center

Cynthia Johnson – Lipps Inc / Photo courtesy Lipps Inc

Cynthia Johnson – Lipps Inc / Photo courtesy Lipps Inc

The Family / Photo by Charles Chamblis

The Family / Photo by Charles Chamblis

Prince’s Career Takes Flight from Minneapolis

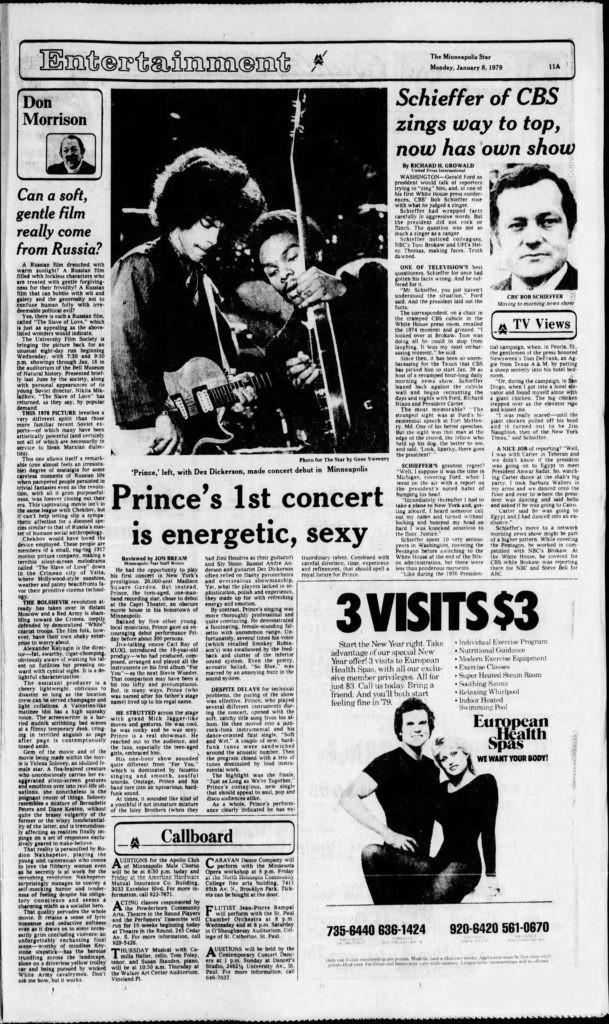

The Minneapolis Star – January 8, 1979

The Minneapolis Star – January 8, 1979

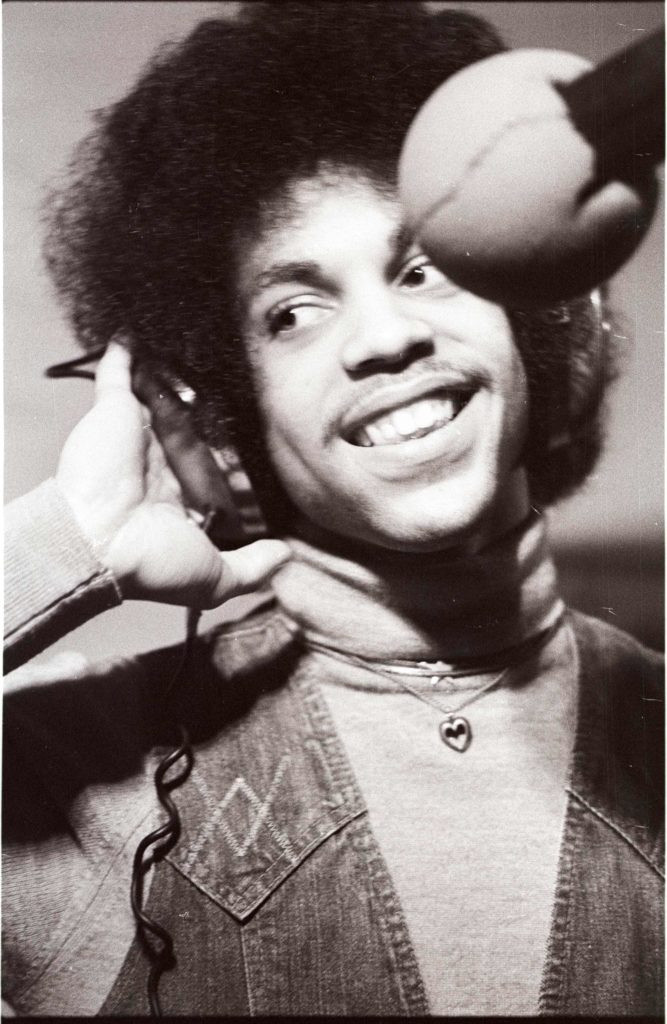

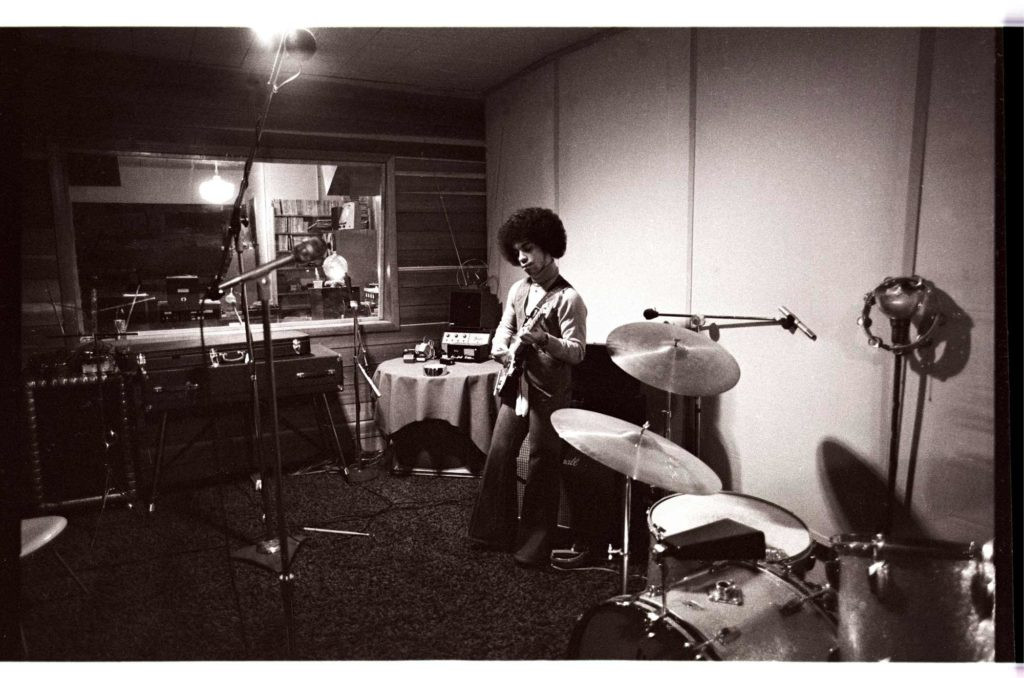

Prince at Moon Sound / Photo by Larry Falk

Prince at Moon Sound / Photo by Larry Falk

Prince was confident in his ability to secure a record deal and create hit music. Immediately after graduating high school, he pursued his ambitions relentlessly. He saved earnings from recording sessions with local bands, including Sonny Thompson’s The Family and 94 East, led by another early mentor, Pepé Willie. He then booked a flight to New York City to stay with his older half-sister, Sharon Nelson, and pitch himself to record labels.

Back in Minneapolis, Prince had recorded a demo tape with Chris Moon, a respected young local producer. Together, they refined a promising song called “Soft and Wet,” which Prince believed would make a strong impression. While Prince faced challenges securing label meetings in New York, Chris Moon took a copy of the “Soft and Wet” demo to Owen Husney, a musician and concert promoter running an advertising office in Minneapolis’s Loring Park area.

Husney, a music industry veteran, had heard countless demos. However, something about Moon’s tape stood out. The music evoked funk and rock icons like Sly Stone, Jimi Hendrix, and Santana, and the vocals, a powerful yet vulnerable falsetto, captivated him.

Owen Husney recalled his initial reaction: “I was immediately struck that this was something different. I turned to Chris and I said, ‘So, who’s the band here?’ And he said, ‘Well, Owen, it’s not really a band.’ And I thought, ‘Oh no, is it a bunch of studio musicians? Because I don’t really want to work with studio musicians; they can’t tour.’ And he said, ‘No, it’s not a studio band. It’s one kid. He’s just turned 18, and he’s singing everything and playing all the instruments.”

Within a week, Prince returned to Minneapolis to sign a management contract with Husney, who pledged to work tirelessly to gain Prince the label attention he deserved. The management deal enabled Prince to move from the Andersons’ basement into his first apartment in Uptown, Minneapolis. It also connected him with the Rivkin brothers: David “Z.” Rivkin, a skilled engineer who helped Prince refine his demos at Sound 80 Studios in South Minneapolis, and Bobby “Z.” Rivkin, who worked at Moon Sound and Husney’s ad agency. Bobby “Z.” drove Prince to photoshoots and appointments and was soon recruited as the drummer for Prince’s new band.

Bobby “Z.” Rivkin remembered their first meeting at Moon Sound: “I first met Prince at Moon Sound. I was walking out one day from Studio B, where I was working, walking by Studio A with the door wide open. I heard the most glorious sound I’ve ever heard. I now know that it was the multi-stacked vocals of ‘Baby.’ I looked in, saw the Afro, and got the side-eye look — we all know now what that was — and won him over with a few jokes. And within a matter of minutes, we hit it off.”

Prince at Moon Sound / Photo by Larry Falk

Prince at Moon Sound / Photo by Larry Falk

Bobby was amazed by Prince’s studio proficiency, watching him seamlessly switch between instruments to create every layer of his tracks.

“In the first hour I met him I was dazzled, amazed, and captivated — which remained for my entire life,” Bobby “Z.” Rivkin stated.

In the evenings, Prince, André, and Bobby jammed in Owen Husney’s office, transforming it into a rehearsal space. As dawn approached, they would rearrange the furniture, allowing Husney and his team to continue their efforts to secure Prince’s first record deal.

Through strategic negotiations, Husney arranged meetings in Los Angeles with Warner Bros. Records, A&M, and Columbia. Within a week, all three labels offered Prince contracts. Within a month, Husney negotiated a three-album deal with Warner Bros., the largest record deal for an unproven artist in modern rock history at the time. Prince was relieved that his manager handled much of the business aspect, allowing him to focus on songwriting. When it was time for Prince to attend a celebratory lunch with Warner Bros. staff, Husney brainstormed creative ways to express their gratitude.

Owen Husney explained Prince’s discomfort with such events: “These type of events were not something that Prince relished going to — as a matter of fact, Prince was probably more comfortable in front of 12,000 people than he would have been in front of maybe 20 people for this signing lunch.”

Prince at Owen Husney

Prince at Owen Husney

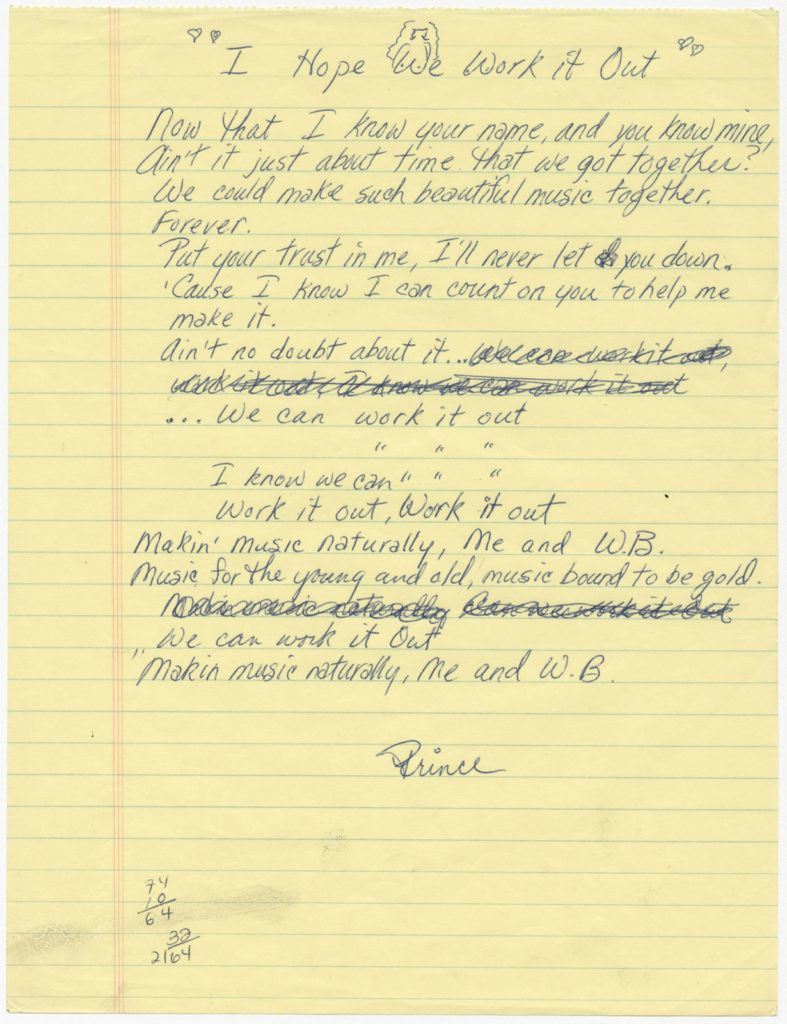

Prince responded in his most fluent language – music. He wrote and recorded a new song specifically for the occasion. After the luncheon, Prince played the Warner Bros. executives the ominously titled track “I Hope We Work it Out.”

Prince I Hope We Work It Out lyric sheet

Prince I Hope We Work It Out lyric sheet

Owen Husney recounted the executives’ reaction: “Everyone was sufficiently blown away with the fact that someone who was 18 years of age had just written a song specifically for a record label. This was Prince showing great faith and asking for trust, and he would in turn give that trust, to make sure that he had a great career. It was a very special time to be there at Warner Bros. watching all of these top executives listen to Prince play this song over the speakers.”

After further negotiations, Prince persuaded Warner Bros. to allow him to not only play all instruments but also produce his debut album, For You, himself – another unprecedented decision. With André Cymone, Prince went to the Record Plant in Sausalito, California, for intense, round-the-clock sessions that lasted nearly two months to complete the album. When marketing For You in 1978, Prince insisted on being presented not as an R&B artist, nor as a black artist, but as a genre-bending pop star capable of appealing to mainstream audiences and receiving airplay on radio stations across all cities.

When assembling his band to translate his solo material to the stage, Prince intentionally chose a lineup that would reinforce his artistic vision. Rejecting the Minneapolis trend of racially homogenous bands, Prince formed what he called a “rainbow” band – diverse in gender and race, mirroring the culturally fluid world he aimed to create through his music. For his solo debut at the Capri Theater in North Minneapolis, close to where he first played his father’s piano, Prince was joined by André Cymone, Bobby Z., keyboardists Gayle Chapman and Matt Fink (a.k.a. “Dr. Fink”), and guitarist Dez Dickerson.

The band’s live performance was still developing towards the polished showmanship Prince became famous for. One memorable technical issue involved Dez Dickerson’s new FM wireless guitar system malfunctioning, picking up CB radio broadcasts and transmitting them through the PA system mid-show.

Bobby “Z.” Rivkin described the debut shows: “The shows were monumental for several reasons, as of course the first shows Prince played live as a solo artist; this band’s debut; and the debut of a lot of wireless technology that caused a tremendous amount of radio frequency to come through the guitars — which in hindsight is kind of humorous, but at the time when you’re hearing police calls and fire calls and radio frequency coming through the speakers while you’re trying to play and perform, it was not so funny at the time.”

Prince at the Capri Theater / Photo by Greg Helgeson

Prince at the Capri Theater / Photo by Greg Helgeson

Bobby “Z.” concluded, “A little rough around the edges, but certainly the beginning of something that we could learn from, and Prince became better and better and better, until he polished the edges off into a shining diamond.”

Leaving those Capri Theater performances, Prince had a clear vision for his future. He knew he wanted to become an artist who could unite diverse audiences through his music and transcend industry barriers to become a global icon. As Prince told MTV in 1985:

“I was brought up in a black-and-white world. Yes: black and white, night and day, rich and poor. Black and white. And I listened to all kinds of music when I was young. And when I was younger, I always said that one day I was going to play all kinds of music, and not be judged for the color of my skin but the quality of my work. And hopefully that will continue.”