Several years ago, a thought-provoking piece in the International Journal of Obesity (IJO) questioned, “BMI, fat mass, abdominal adiposity and visceral fat: where is the ‘beef’?” This commentary sparked important discussions about how we measure obesity and understand the relationships between simple body measurements and more complex assessments of body fat. It highlighted that Body Mass Index (BMI) and waist circumference (WC), common anthropometric measurements, showed similar correlations with total fat and abdominal visceral fat (AVF). Despite advancements in obesity research, confusion persists about the best ways to use these simple measures to estimate body fat, particularly in children and adolescents.

Building upon this earlier work, we now look specifically at children and adolescents, expanding the investigation to include data from dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA), a more advanced body composition tool. Our study involved a diverse group of 380 young individuals aged 5–18 years, encompassing white and African American girls and boys across a spectrum of weight categories from normal to obese. Trained professionals used standardized techniques to measure WC and BMI. Fat mass (FM) and trunk fat were determined using a whole-body DXA scanner. To assess AVF mass, we used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), taking multiple cross-sectional images of the abdomen. Statistical analysis was then performed to understand the relationships between these different body measurements, considering age and different race and sex groups.

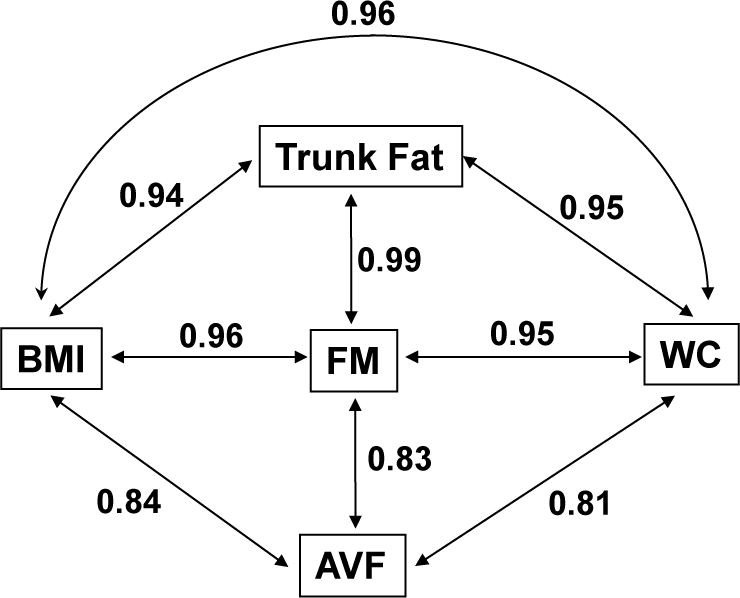

The results of our correlation analysis are visually summarized in Figure 1. Notably, within each of the four groups (white girls, African American girls, white boys, and African American boys), the age-adjusted correlations between BMI and WC were exceptionally strong, averaging around 0.96. Similarly, the correlations between fat mass and both BMI and WC were also very high, approximately 0.96 and 0.95, respectively. Trunk fat also showed strong correlations with BMI (around 0.94) and WC (around 0.95). As anticipated, the correlations involving AVF were somewhat lower but still significant. AVF correlated with BMI at approximately 0.84, with WC at 0.81, and with FM at 0.83. Importantly, the consistency across the different race-by-sex groups indicates that these relationships hold true regardless of these demographic factors in children and adolescents.

Figure 1

Figure 1

Our findings in children and adolescents mirror those previously reported in adults, suggesting a consistent pattern across age groups. In adults, waist circumference and abdominal sagittal diameter have often been considered the best anthropometric indicators of AVF. Waist circumference, in particular, is widely used due to its simplicity. However, as demonstrated in adults and now in our study of children, waist circumference, while useful, isn’t a direct and exclusive measure of AVF. Instead, it’s more strongly linked to total fat mass and BMI. Therefore, waist circumference should primarily be interpreted as an indicator of overall body fatness rather than specifically visceral fat. Our analysis further reveals that BMI and WC are similarly correlated with AVF in children, although these correlations are weaker than their associations with total fat mass.

Based on these cross-sectional observations, BMI appears to be just as effective as waist circumference and DXA-derived fat mass in reflecting AVF levels in young people. Recent advancements have made DXA-based AVF measurements more accessible. This raises questions about the common belief that simple anthropometric measurements can accurately provide clinically meaningful insights into visceral fat. This assumption appears to be questionable.

These observations have important implications for how we understand and address obesity-related health risks in children. For instance, waist circumference is frequently included in clinical definitions of metabolic syndrome in both adults and children. In the context of metabolic syndrome, WC is often viewed as a marker of “abdominal” obesity, with less emphasis on generalized obesity. However, our results suggest that the unique contribution of waist circumference in defining metabolic syndrome, specifically in relation to AVF, might be less significant than previously thought. In fact, a general obesity marker like BMI, or a measure of total body fat, which is essentially what waist circumference reflects, could serve a similar purpose in the definition of metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents.

Ultimately, our findings are relevant to diagnosing obesity-related health concerns in children and for assessing body fat distribution in growth and development studies. It’s unlikely that we can accurately track changes in specific fat depots, like visceral fat, using only anthropometric measurements. If the goal is to precisely measure AVF in children, waist circumference, or other simple anthropometric measures, are unlikely to provide a truly valid quantification of visceral fat. However, it’s important to remember that waist circumference remains a good indicator of overall adiposity and performs comparably to BMI in both children and adults for this purpose.

Acknowledgments

The research presented here was supported by National Institutes of Health grant RC1DK086881-01.

Footnotes

Clinical Trials Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov: identifier NCT01595100

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.