Junji Ito, a master of horror manga, is known for crafting tales that delve into the bizarre and terrifying. Among his extensive works, “The Town Without Streets” initially appears as one of his more perplexing stories. On the surface, the narrative seems to wander, introducing a series of supernatural occurrences that lack clear connections or explanations. Unlike Ito’s signature style, which typically focuses on a single, disturbing phenomenon impacting individuals or communities – think of the spiral obsession in Uzumaki or the alluring madness of Tomie – “The Town Without Streets” feels fragmented. However, dismissing it as simply “lame” upon a first read overlooks the story’s subtle yet profound shift in focus. The true horror doesn’t reside in the disparate supernatural events themselves, but in how they converge on the protagonist, Saiko. This story isn’t primarily about the supernatural invading lives; it’s about how these invasions reflect a deeper, more personal violation. Let’s delve into a summary for those unfamiliar with this unsettling tale.

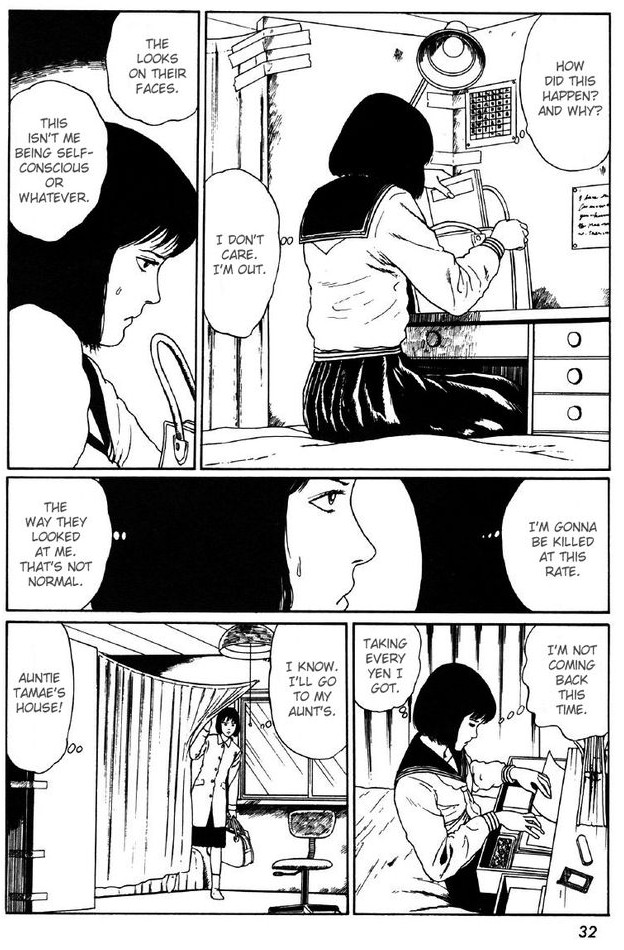

The story unfolds with a disturbing incident involving Kishimoto, a classmate of Saiko. He infiltrates her home at night, whispering to her in her sleep, attempting to manipulate her subconscious into romantic affection. This unsettling act is cut short when Kishimoto becomes a victim of Jack the Ripper, a serial killer whose actions Saiko witnesses in her dreams. Following this, Saiko experiences another form of violation: her own family begins to relentlessly spy on her. They drill holes in walls and peer through door cracks, yet vehemently deny their actions even when confronted with undeniable evidence. This blatant gaslighting and invasion of privacy forces Saiko to seek refuge with a classmate, a temporary escape from her own home. The escalating sense of threat is underscored by bizarre incidents where Saiko injures her brother and father, who then dismiss these events as accidental and misremembered. Saiko’s world is under siege, not just by one, but by a multitude of unseen, external forces.

Saiko's family spying on her

Saiko's family spying on her

The panel above, taken out of context, could depict almost any form of domestic abuse. Saiko’s desperate need to escape her family stems from their terrifying behavior, a fear for her own safety. While in this instance, the fear is triggered by their spying and deceit, it could easily be interpreted as a response to physical, sexual, or emotional abuse – the insidious manipulation of gaslighting. Fortunately, Saiko possesses a strong sense of self-preservation and recognizes the urgent need to flee. Her escape leads her to Kosato, the town where her aunt Tamae resides.

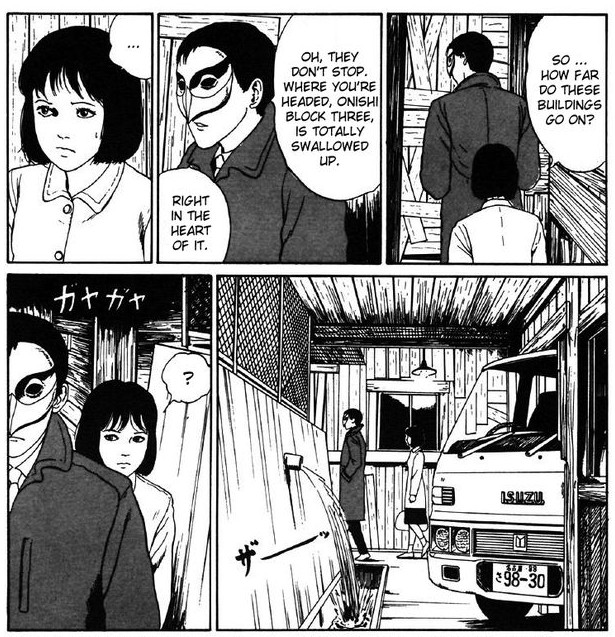

Upon arriving in Kosato, Saiko discovers a town consumed by an unsettling phenomenon: self-constructing shanty buildings that relentlessly encroach upon every space, covering roads and rivers, and connecting houses into a claustrophobic maze. Navigating Kosato requires traversing through the homes of strangers, and refusing entry is deemed a civic offense. This complete erosion of privacy has led the townspeople to adopt masks, a desperate attempt to reclaim anonymity in a world without private space. Saiko, adopting a mask herself, seeks out her aunt Tamae with the assistance of a mysterious man.

Kosato's encroaching buildings

Kosato's encroaching buildings

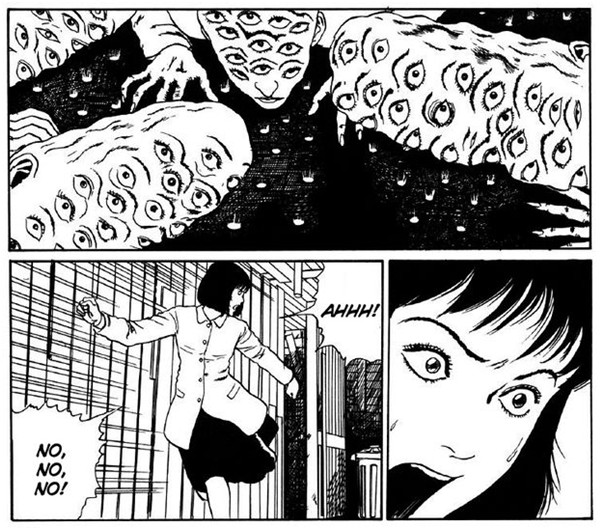

The relentless expansion of the town is depicted starkly, even engulfing cars and fences. When Saiko finally reaches Tamae’s home, she finds her aunt in a state of shocking resignation – lounging naked in her house, urging Saiko to do the same. Tamae’s home is no sanctuary; it is a thoroughfare, with townsfolk constantly passing through, day and night. Peepholes, mirroring those in Saiko’s own home, are drilled into Tamae’s walls, but here, they are not the clandestine tools of family members, but open portals for the town’s pervasive voyeurism. Tamae, having surrendered to this constant scrutiny, has abandoned clothing as futile, embracing the town’s invasive gaze. She even threatens to strip Saiko, attempting to force her niece into the same acceptance. Terrified, Saiko flees, catching glimpses of unsettling figures peering through the peepholes – the monstrous faces of the town’s voyeurism made manifest.

Monsters peeping through holes

Monsters peeping through holes

Fleeing through the labyrinthine streets of Kosato, Saiko again encounters the mysterious man who offered help. He offers to guide her out of the town, and she accepts, only to recognize him as Jack the Ripper from her nightmares. He chillingly confesses that murdering Kishimoto was an act of salvation, claiming Kishimoto intended to kill Saiko and that killing is the only thing that brings him peace. Just as Jack the Ripper turns on Saiko, Tamae intervenes, stabbing him to death. Saiko desperately pleads with Tamae to escape Kosato, but Tamae, numb and defeated, retreats back into the oppressive town, leaving Saiko to escape alone.

Saiko escaping Kosato

Saiko escaping Kosato

This is the unsettling narrative of “The Town Without Streets.” While it possesses a clear narrative arc, the story feels disjointed, a collection of disturbing elements without obvious connection. Are the voyeuristic tendencies linked to the self-building town? Tamae’s house, with its profusion of peepholes, seems to be at the epicenter of both phenomena. Does voyeurism transform people into multi-eyed monsters, or do these peepholes simply attract such entities? Kishimoto’s initial actions and the introduction of Jack the Ripper feel almost tangential. Why is Jack the Ripper even present, when the story could seemingly progress without him? These are the questions that led to my initial unimpressed reaction. The usual Ito narrative structure, focusing on a singular phenomenon and its impact, falters here due to the multitude of seemingly unrelated horrors. They lack thematic coherence beyond a general sense of creepiness and intrusion.

However, to truly understand “The Town Without Streets,” we need to shift our perspective. The unifying thread isn’t a single supernatural element, but Saiko herself. She is a young woman, likely of high school age, and the events that plague her are all, in essence, violations of her personhood and privacy. Saiko’s experience within this nightmarish world can be interpreted as a potent allegory for the experience of growing up female in a misogynistic society. This is the lens through which we can truly unlock the story’s chilling relevance.

Consider Kishimoto’s method of pursuing Saiko: a clandestine invasion of her private space, whispering into her ear as she sleeps. His intent is to manipulate her dreams, forcing himself into her subconscious to manufacture affection. His shyness is cited as the reason for this invasive approach, rather than direct communication. This speaks volumes about entitlement and a disregard for genuine connection. Kishimoto believes he has a right to Saiko’s affections, so much so that he bypasses conscious interaction, opting to impose himself upon her most vulnerable, private state. It’s not a stretch to see this as a metaphor for men who seek to bypass the complexities of genuine relationships, aiming to jump directly to intimacy and affection without consent or effort. Countless women like Saiko, regardless of social standing, are forced to rebuff such unwanted advances, often starting at an alarmingly young age. This element, rooted in Saiko’s experience as a young woman, makes the allegorical reading compelling.

Next, the relentless voyeurism of Saiko’s family. Without explanation, they obsessively spy on her, drilling holes to watch her every move, and then gaslight her with denials and lies. Rather than simply labeling this “the male gaze,” let’s consider how girls are raised under constant scrutiny. “Boys will be boys,” but girls are subjected to relentless monitoring and judgment regarding their behavior and appearance, all in the name of shaping them into “acceptable women.” This constant surveillance, though perhaps less overtly invasive than drilling holes in walls, persists even today, often masked by rhetoric of empowerment and feminism. Saiko’s family embodies an extreme version of this societal pressure, but real-world parallels are abundant: from constant behavioral corrections to invasive actions like removing bedroom doors, monitoring phones, and demanding constant updates on a daughter’s life. Saiko’s feeling of being gaslit mirrors the experience of many young women whose sense of self and independence is consistently undermined. Her flight from her family and subsequent masking in Kosato become desperate attempts to shield herself from prying eyes.

Tamae’s situation takes this voyeurism to another level. As an adult woman in her own home, she is subjected to the same invasive gaze, but from anonymous strangers. The same peepholes riddle her walls, but now, instead of family, monstrous, multi-eyed figures peer through them. Tamae’s response is one of resignation, a disturbing acceptance of her lack of privacy. If she cannot escape the constant observation, she chooses to embrace it, symbolized by her nudity. This could be interpreted, albeit tenuously, as a dark allegory for individuals in exploitative situations, such as sex work, who, facing inevitable exploitation, choose to take control in the only way they can – by commodifying what will be taken from them anyway. “If people are going to take naked pictures anyway, why not profit from it?” Tamae’s stark nakedness, juxtaposed with Saiko’s clothed state, serves as a brutal reminder of the privacy Saiko is on the verge of losing. Tamae’s attempt to strip Saiko can then be seen as a twisted form of initiation, a desire to accelerate Saiko’s “loss of innocence” and acceptance of this pervasive voyeurism. However, even in her resignation, Tamae retains a flicker of protectiveness, killing Jack the Ripper and enabling Saiko’s escape, suggesting a deep-seated desire to shield Saiko from the full extent of this oppressive reality, even if she herself cannot escape.

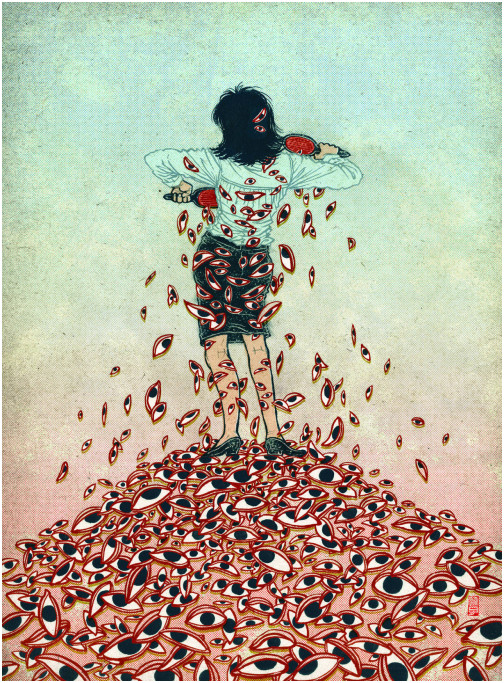

Dusting Off the Male Gaze by Yuko ShimizuYuko Shimizu

Dusting Off the Male Gaze by Yuko ShimizuYuko Shimizu

Even the self-building streets of Kosato contribute to this theme of violated womanhood. These ever-encroaching structures dismantle the boundary between the private and public spheres. The home, traditionally a sanctuary of privacy, becomes an extension of the public street. Attempts to maintain privacy are criminalized. Private spaces are essential for individuals to shed societal personas and exist authentically. They are often the few places where women can escape the relentless societal pressures to conform to ideals of appearance and behavior. In Kosato, this escape is eliminated. This can be seen as a metaphor for a world where women are increasingly denied private space, both literally and figuratively, and are disproportionately affected by the erosion of privacy. In our own world, trends like Airbnb, which blurs the lines between private homes and public spaces, and social media, which encourages the publicization of private lives, contribute to this pressure, forcing individuals, particularly women, to constantly perform and conform in increasingly public spheres. The encroaching walls of Kosato mirror the ever-tightening constraints of conformity imposed upon women as privacy diminishes in modern society.

Jack the Ripper’s role, while seemingly extraneous, becomes relevant when viewed through this allegorical lens. He facilitates Saiko’s movement through Kosato, and his death at Tamae’s hand enables her escape. However, narratively, he could be removed. Kishimoto’s initial attack could be thwarted by Saiko alone, and other characters could have aided her escape. So, why include Jack the Ripper? The answer lies in the gendered nature of serial killers. He confesses his intent to kill Saiko, echoing his murder of Kishimoto, revealing a pattern of violence directed at women. Serial killers are overwhelmingly male, and their victims disproportionately female. Explanations for this often overlook the crucial point: the victims are primarily from an oppressed group (women) targeted by their oppressors. Historically, many Japanese serial killers have exclusively targeted women. Interviews with serial killers often reveal deep-seated misogyny. Therefore, Jack the Ripper, in this context, embodies the most extreme and terrifying manifestation of gendered violence: a male killer fixated on the death of women.

The cumulative events in “The Town Without Streets” are experiences uniquely resonant with the female experience. Saiko is perpetually watched, from Kishimoto’s initial intrusion to her family’s surveillance and the masked gazes of Kosato’s inhabitants – echoing the visual metaphor of Yuko Shimizu’s artwork. Her agency is constantly undermined; her desires manipulated, and her reality gaslit by those around her, leading her to question her own sanity. For me, the story becomes a chillingly insightful narrative about the pervasive threats and violations that shape a young woman’s experience in the world. Whether Ito consciously intended this allegorical reading is open to interpretation. However, the story’s very ambiguity and seemingly disjointed nature amplify this feeling of disorientation and vulnerability. The fluctuating levels of threat and Saiko’s constant uncertainty about her safety mirror the unpredictable and often incomprehensible nature of misogynistic oppression. Re-examining “The Town Without Streets” through this lens transforms it from a merely “lame” horror story into a disturbingly effective commentary on the insidious forms of everyday misogyny, solidifying its place as one of Ito’s most profoundly unsettling and relevant works.

Share this:

Like Loading…